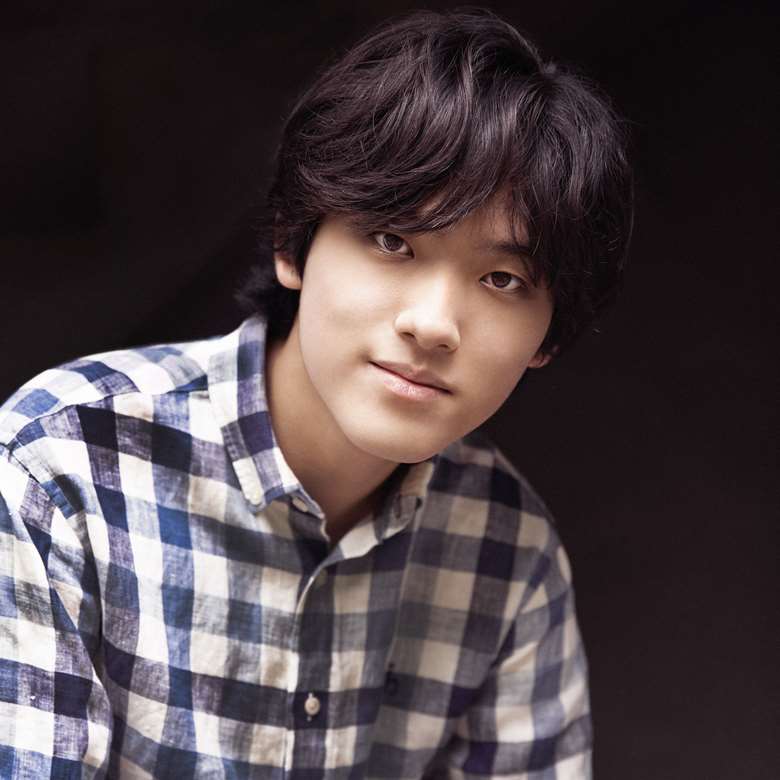

Yunchan Lim: the whole world in his hands

Jed Distler

Thursday, September 21, 2023

When Yunchan Lim became the youngest-ever winner of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition last year, he launched a major career with a string of unforgettable performances. Jed Distler reports on a young pianist of exceptional promise

I first encountered Yunchan Lim, as I suspect most piano mavens around the world did, while watching the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition’s 16th edition online, live from Fort Worth, Texas. His preliminary round stood out for some of the most stylish and elegant Couperin and Mozart pianism I’d ever heard, topped by an agile and rhythmically vivacious account of Chopin’s Variations on ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Op 2. Small wonder that a YouTube viewer described Lim as ‘a 40-year-old in an 18-year-old body’. Naturally, Yunchan Lim made it to the quarter-finals, where he offered a smartly programmed and superbly delivered set containing the Three-Part Ricercar from Bach’s The Musical Offering, Scriabin’s Second Sonata and Beethoven’s Eroica Variations.

After sailing through to the next round, the announcement that Lim planned to devote his entire semi-final recital to Liszt’s complete Transcendental Études created a stir throughout the international piano community. Could this youngest of the 2022 Cliburn finalists successfully bring off such an audacious test of technical wherewithal, musicianship and stamina? The answer was a most emphatic, unambiguous ‘yes’! Lim’s astonishing yet intelligent virtuosity and his total immersion in Liszt’s idiom truly defined ‘transcendental’. He launched into the opening ‘Preludio’ while the audience was still applauding, and tossed of the second étude’s broken double notes and unwieldy leaps without breaking sweat. I have never heard ‘Mazeppa’ played with such minimal bluster and maximum nobility, not to mention interlocking octaves in ‘Wilde Jagd’ that made Cziffra’s signature trick sound arthritic by comparison.

Yunchan Lim’s thrilling performances at the Cliburn Competition won over audience and jury alike

This live performance is now being issued on the Steinway & Sons label, both on CD and on streaming platforms – Yunchan Lim’s first recording, with the promise of a debut studio album still in the future. Listening again to this musical and technical tour de force it is clear that, even when new recordings of Liszt’s Transcendental Études seem to be issued every other month, this is an account to be placed alongside any personal favourites one might have, whether by Lazar Berman, Claudio Arrau, Bertrand Chamayou or countless others, as a benchmark reference version, the vivid music-making caught in the inspired heat of the moment.

In retrospect, this Liszt performance was just a warm‑up act for what one online commentator called ‘The Rach 3 heard round the world’. Not since the heyday of Vladimir Horowitz and Van Cliburn himself has a performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 3 become the talk of the town, with the entire piano community weighing in, from 11 million-plus YouTube viewers and seasoned pros to the Cliburn jury itself. Perhaps no one enjoyed the performance more than its conductor, Marin Alsop, who also headed the jury. ‘He’s a musician way beyond his years,’ she told The New York Times. ‘Technically, he’s phenomenal, and the colours and dynamics are phenomenal. He’s incredibly musical and seems like a very old soul. It’s really quite something.’

Yet when Lim visited me for coffee not long after the competition (along with silver medallist Anna Geniushene, bronze medallist Dmytro Choni and the Cliburn’s director of communications and digital content Maggie Estes), he expressed dissatisfaction with his Rachmaninov, saying that he hardly played up to his full potential. While most competitors would give their eye teeth to attain Lim’s overnight success and acclaim, the young pianist seemed unfazed by the spotlight. More than once he mentioned his fantasy of buying property in the mountains, away from the public, where he could work in isolation to his heart’s content.

Yunchan Lim (right) with his fellow Cliburn Competition medallists Anna Geniushene and Dmytro Choni

‘I’ve been exposed to music since I was born,’ Lim told me recently in a follow-up interview we conducted over email. ‘We had a CD player at home and my parents always played a variety of music, even though they were not musicians at all. So I’ve enjoyed collecting records since then and now I have an enormous collection of them.’ He began piano lessons at the age of seven, and only one year later participated in his first competition. ‘The piece I played in that competition was Chopin’s Waltz in B minor, Op 69 No 2. At that time, my first teacher, Ms Kim Kyung Eun, recommended that I listen to recordings by Evgeny Kissin and Sergey Rachmaninov. Looking back now, it seems like starting my musical life with Kissin and Rachmaninov was a divine intervention.’ From there Lim delved further into the Russian school, absorbing recorded performances by Heinrich Neuhaus, Stanislav Neuhaus, Vladimir Sofronitsky and Maria Yudina. He also cites Alfred Cortot, Ignaz Friedman, Edwin Fischer and Artur Schnabel as major influences, not to mention the impact of Carlos Kleiber, Sergiu Celibidache, the Quartetto Italiano and Jussi Björling.

Lim is also quick to mention the influence of his teacher Minsoo Sohn, who recognised his teenage student’s extraordinary potential. ‘At first he was a little bit cautious’, Sohn told The New York Times, ‘but I immediately noticed that he was a huge talent. He’s very humble, a student of the score and he isn’t over-expressive.’

‘Lim’s astonishing yet intelligent virtuosity and his total immersion in Liszt’s idiom truly defined “transcendental”’

The one-year delay of the Cliburn Competition due to the pandemic made it possible for Lim to qualify when he turned 18. At his teacher’s suggestion, Lim gave it a try. Once the pianist arrived in Fort Worth, with his mother in tow, he prepared like an athlete, putting in as many as 20 hours into a practice day, fuelled by proteins and carbohydrates. Proper balance and alignment between mind and body is important to Lim. Perhaps this accounted for the generally outward calm and expressive economy of his platform demeanour during the solo rounds, in contrast to the gesticulations, facial grimaces and other physical mannerisms typical of so many competition practitioners. But then, in his recent performance of Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto for his debut with the New York Philharmonic, critic Zachary Woolfe observed the pianist’s upper body ‘jackknifing toward the keys at flourishes, with his left foot stomping’.

Lim’s Cliburn victory launched a steady stream of recital and concerto engagements on four continents over the past year. Discussing Lim’s Tokyo debut in February, playing Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto under Mikhail Pletnev’s leadership, the critic Nahoko Gotoh wrote: ‘From the opening solo bars, [Lim] captivated the audience with his elegance and assuredness of a veteran pianist; the leggiermente passages were crisp and light, but he could also produce weightiness, for example in the development section. There were some breathtakingly lyrical moments in the slow movement, followed by pretty speedy and nimble playing in the finale.’

Interestingly, Lim chose a relatively chaste programme for his UK debut recital at London’s Wigmore Hall in January. The recital remains available for online viewing, and such a radical shift in direction and perspective helps to broaden our understanding of his range and musicianship. The first half is taken up by William Byrd’s arrangement of John Dowland’s Pavana Lachrymae and Bach’s Three-Part Sinfonias (or Inventions), BWV787-801, which Lim presented in his own running order. The sheer beauty of sound and the unforced clarity that Lim brings to the contrapuntal textures represents the kind of undemonstrative control that doesn’t sound virtuosic on the surface, yet can be achieved only by a true virtuoso. You’ll notice how he draws out the tension in the Bach F minor Sinfonia’s chromatic harmony through touch and timbre alone, which is easier said than done. In the all-Beethoven second half, his vividly characterised performance of the Op 33 Bagatelles leaves no detail unaccounted for, yet never lapses into fussiness or exaggeration. Some of his faster tempos in the Op 35 Eroica Variations rush from the starting gate like unbridled puppies freed from their cages, but you can’t deny the pianist’s sheer joy in the music’s humorous touches.

To get a fuller sense of Lim’s poetic gifts, listen on YouTube to his rivetingly spacious and songful rendition of Brahms’s A major Intermezzo, Op 118 No 2. This reinforces the impression I gained hearing Lim in concert last autumn: his performance of Brahms’s Four Ballades, Op 10, offered masterclasses in spacing, proportion and long-range planning, and was matched by atmospheric, unselfregarding readings of the two Liszt Légendes and a Mendelssohn Fantasy in F sharp minor, Op 28, that bypassed the piano en route to the music.

That Lim clearly does not follow the repertoire party line was further confirmed in our interview, when I asked the pianist about future programme ideas. ‘If I were to play Rossini’s “Preludio religioso” from the Petite Messe solennelle, Franck’s Prélude, Choral et Fugue, plus Liszt’s Nuages gris and Sonata in B minor in one recital, I think it would be great.’ So would countless piano fans! An all-Chopin programme is scheduled for Lim’s February 2024 Carnegie Hall recital debut in New York. Further recordings will be widely anticipated.

Like many young super-virtuosos, Lim adores the transcription repertoire, and hopes to make original contributions to that genre, as well as pursuing his creativity further. ‘When I was attending the Korea National Institute for the Gifted in Arts, my teacher for vocal training and ear training, Jeon Minjae, recommended that composition and transcription should be done by people who play the piano well. Since then, I have attempted to arrange solo and two-piano versions of pieces such as Schubert’s Winterreise and Mahler’s Symphony No 8, but I did not like any of them and discarded them. I also love jazz. Bill Evans, of course, is also a great artist, but for me, the music of Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson resonates with me the most deeply. I want to express music freely on stage like these two, but I’m not sure if I can do so myself.’

Such humility is typical of Yunchan Lim. What this astonishing young pianist can already express and communicate through his instrument at this early point in his career, together with this humble self-effacement, promises a long and fulfilling artistic journey that we can all look forward to sharing.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today