Brahms's Symphony No 3: a guide to the best recordings

Richard Osborne

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Richard Osborne surveys the finest recordings of the Third Symphony

‘It is enormously rewarding – one of the world’s grandest bracers. What a lift in those themes, and what tenderness beneath their power! Brahms for ever!’

So wrote WR Anderson in Gramophone in September 1935 at the end of a survey during which he had struggled to decide whether Leopold Stokowski or Willem Mengelberg had his vote in Brahms’s Third Symphony. Had Clemens Krauss’s superb 1930 Vienna Philharmonic HMV recording been available, WRA might have worried less. It is none the less remarkable how well this most elusive of great 19th-century symphonies was served in the early years of electronic recording.

The Third is the most personal of Brahms’s four symphonies, and the shortest. It is a glorious work, yet a deeply troubled one. And there is the added peculiarity of its being, unusually for its genre and age, a symphony in which all four movements end quietly.

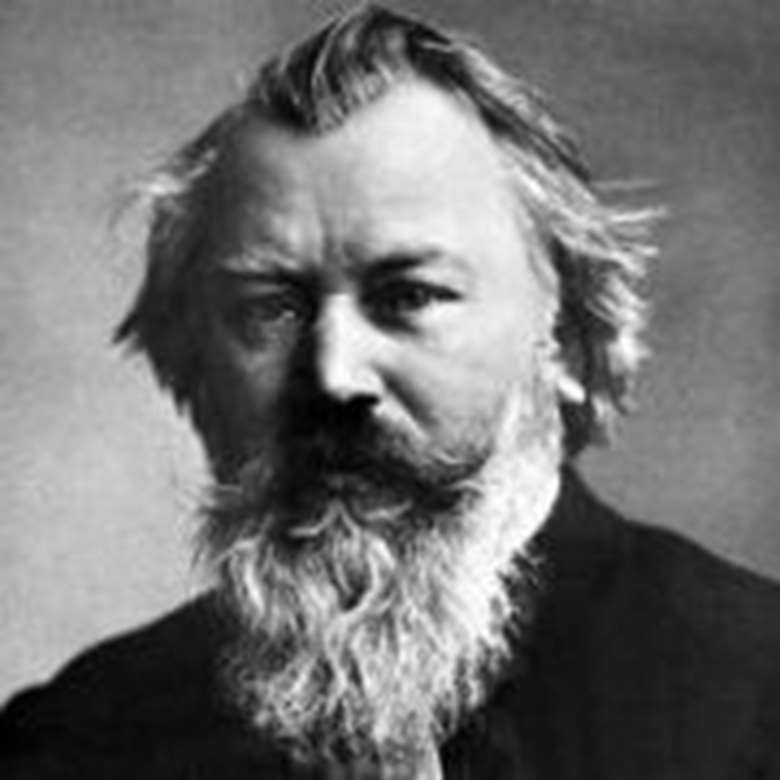

Brahms was 50 and at the zenith of his art when he completed it in 1883. He remained resolutely silent as to the work’s inner content yet the music itself provides clues. The great summons at the opening rests on the notes F-A-F (‘Frei aber froh’, ‘Free but happy’), a cipher Brahms had used in response to his friend Joseph Joachim’s motto F-A-E (‘Frei aber einsam’, ‘Free but lonely’) in that halcyon age in Düsseldorf in the early 1850s when the young Brahms was taken under the wing of Robert and Clara Schumann. It can be no coincidence that there is a clear echo of Schumann’s own Third Symphony, the Rhenish, in the passionate down-sweep of the strings in bar three of the Brahms. Were Schumann and his troubled end a cue for this great outpouring?

Brahms’s use of the F-A-F cipher is itself ambiguous. The ‘A’ in bar two is an A flat, tipping the work instantly towards the minor key, with a sinister tritone adding to the sense of angst. And what of the later transformation of the exposition’s gracious dance into a nightmare waltz, or the crisis-laden mood of much of the work’s finale? Time and again during this symphony, WB Yeats’s words come to mind: ‘For Nature’s pulled her tragic buskin on/And all the rant’s a mirror of my mood.’

Too multifaceted to be known from a single interpretation, the Third Symphony can be played classically or romantically, briskly or with great breadth. Brahms himself was not prescriptive when it came to such matters. Tempo modification fascinated him to the point of obsession, but he knew that speed itself is relative. Metronome marks were anathema to him (‘I have never believed that my blood and a mechanical instrument go well together’), and he mistrusted musicians who put their faith in them.

FIRST RECORDINGS

The earliest extant recording of the Third Symphony was made in 1928 by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. It is finely played without undue resort to saturated string tone. The principal drawback is an over-inflated account of the troubled pastorale which is the work’s Andante. At a little over 10 minutes, Stokowski’s performance of this movement is not quite as protracted as his 1959 Houston version, but it remains out of scale with the work as a whole. The 1932 Willem Mengelberg recording is a somewhat portentous affair. The first movement, complete with its exposition repeat, is positively Gladstonian and the two inner movements are much pulled about. Neither of these versions compares well with the 37-year-old Clemens Krauss’s 1930 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, which remains one of the truest of all accounts of the symphony on record. It is a beautifully articulated performance, strongly drawn yet rhythmically crisp, with a slow movement that is every bit as expressive as Stokowski’s but better paced. Sergey Koussevitzky’s 1945 Boston recording (RCA, 7/74R) has similar qualities to Krauss’s, though there is a fearful solecism in bar two where Koussevitzky allows the trumpets’ high pedal F to overtop the orchestra, transforming Brahms’s F-A-F into a blandly tautological F-F-F.

Starting the symphony is not easy, as one of its most sure-footed contemporary interpreters, Marin Alsop, told James Jolly in a Brahms symposium in Gramophone in March 2005: ‘It’s quite tricky to find the right tempo that propels it without pushing it too much. This is crucial to Brahms: giving it space without making it sound slow.’ She added, ‘I think great orchestras can really do that. They can fill in the time.’ One way of increasing the thrust of the opening is to make an unmarked crescendo in the already excoriating second bar. George Szell does this to searing effect in a live Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra performance in 1952, though not in his more generously paced 1964 Cleveland studio recording. As Alsop suggests, it takes exceptional skill successfully to drive this first movement forward and yet retain a weight and presence. Szell, who, like Furtwängler, knew the work inside out and played it in different ways on different occasions, had that ability.

CLASSIC versus ROMANTIC

Furtwängler believed that ‘naturalness of utterance’ is ‘the difficult, the ultimate thing’ in Brahms interpretation. (‘Preternatural’ would be the best word to describe his own Brahms.) If what we are looking for is directness and clarity of line, with the score’s frequent technical difficulties unassumingly resolved at no cost to the music’s power and presence, then Felix Weingartner with the LPO in 1938, Otto Klemperer with the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1957, Sir Adrian Boult with the LSO in 1970 or James Loughran with the Hallé in 1975 – all English orchestras – collectively emerge as well-nigh exemplary interpreters. A fifth such performance, by Günter Wand and the North German Radio SO (1983) based in Brahms’s native Hamburg, also has that distinctive northern European pedigree.

None of these classicised readings would be of any account if they were not driven on by a powerful sustaining pulse. Dogged good sense (and the kind of short-windedness that can often accompany it) is a great subverter of this particular work, as we can hear in versions as far apart in time as Eduard van Beinum’s in 1956 and David Zinman’s in 2010. Nor is a tried-and-tested reading guaranteed to take flight on every occasion. Karl Böhm, Marek Janowski and Wolfgang Sawallisch all impressed with first recordings of the Third, but failed to repeat the effect on later occasions.

Wilhelm Furtwängler created his own sense of occasion. For him the Third Symphony was a work of sudden surges, delayed charges and buried detonations. ‘Subjective?’ asked Michael Oliver in Gramophone of Furtwängler’s Brahms. ‘Certainly. If one of a conductor’s functions is to realise the composer’s intentions, another is to convince you that those intentions matter.’ Furtwängler conducted the symphony many times, yet by a happy chance his two extant Berlin-made recordings are complementary. The 1954 performance is the more serene, the 1949 – an experience unique in the annals of the work on record – the more impassioned, an essay in what Furtwängler himself called ‘the energy of becoming, inexorability and the force of onward motion’. So caught up is Furtwängler in Brahms’s tragic mood, he even adds to the composer’s own careful revisions of the orchestration by providing minatory timpani rolls either side of the arrival of the finale’s second subject. Furtwängler’s is a forward-moving performance built on an epic scale, a point underlined by his decision here (though not in 1954) to take the exposition repeat.

COURAGE AND CONVICTION

The structure of the symphony’s opening movement tends to be weakened if the exposition repeat is ignored. This is particularly so in performances that further undermine the structure with the kind of unwanted accelerations and decelerations favoured by Sergiu Celibidache in his live 1976 Stuttgart performance. The fact that Celibidache’s 1987 Munich recording is unstable in entirely different ways suggests that he never (as Felix Weingartner put it) fully ‘assimilated’ the work. Not that he was alone in this. The 1952 RCA recording from Arturo Toscanini was a movement-by-movement identikit assemblage based on the old man’s attempt to memorise the best features of four separate NBC radio performances. It was a curious procedure. Cloning performances, one’s own or other people’s, is doubly defeating in the context of a work that openly engages the question of the vulnerability of private sensibility and the value of individual vision. Yet, such was Toscanini’s influence, even the self-evidently flawed 1952 RCA recording was slavishly copied, right down to the maestro’s egregious subito piano in bar six. A recording by James Levine and the Chicago SO offers a particularly close paraphrase. Ironically, it was Toscanini’s protégé Guido Cantelli who best grasped, or was best able to realise, what his mentor was attempting. Cantelli’s 1955 Kingsway Hall recording was notable in its day. If there was more impulse to the first movement, and a clearer sifting of internal voicings, it would be a front-runner still.

A conductor who omits the exposition repeat but whose broad tempi and richly assimilated understanding of the symphony’s argument convinces one of the rightness of his action is Kurt Sanderling in his 1972 recording with the Dresden Staatskapelle. This is an epic traversal of the symphony whose 72-bar exposition needs no repetition, so completely does Sanderling set out the symphony’s terrain to our gaze. You might think that such an effect could be achieved only by a conductor in the full maturity of his art. This is true, though in 1970 Bernard Haitink, the then-41-year-old principal conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, offered a similarly broadly based reading. It is a version that continues to impress with the certainty of its aim and the clarity and purity of its sound – a collaborative act between conductor, orchestra and the record’s producer Jaap van Ginneken, the unaffected truthfulness of whose recordings remain a lesson to us all. Haitink’s approach to the symphony has not greatly changed down the years but ways of preserving it have become a good deal more slipshod. His 2004 LSO Live account is not only less well played, it is much more crudely recorded.

The principal danger of such slow-drawn readings is the loss of concentration in lyric subjects and at critical points of transition. This is one of the reasons why Leonard Bernstein’s interminable 1981 Vienna Philharmonic recording should be avoided at all costs. Mariss Jansons is far less self-indulgent in his broadly argued live 2010 Bavarian Radio performance, but there are pitfalls here which even he doesn’t entirely avoid. On paper Carlo Maria Giulini’s 1990 Vienna recording should also come into this category, but Giulini’s speeds are deceptive. As Edward Seckerson has noted, ‘His innate sense of architectural coherence and the sheer will of his commitment keep heart and mind engaged.’ Exquisitely painted by the orchestra, this is a reading that can be set beside Sanderling’s in terms of its power and long-term vision.

Fifty-minute traversals of the symphony, such as we have from Haitink, Sanderling and Giulini, occupy a very different world to the kind of 30-minute lick-and-a-promise performances served up by Bruno Walter in Vienna in 1936 and New York in 1953. How different these are from the 83-year-old Walter’s broader, more rhythmically stable but not less vivid 1960 California-made recording with the hand-picked Columbia Symphony Orchestra. This is one of the great Brahms Thirds – what one imagined Walter’s Brahms always was but which the early recordings gainsay. Comparison can be made here with Eugen Jochum: his 1938 Hamburg performance barely holds together; his 1956 Berlin version is much improved; his 1976 LPO recording (EMI, 10/77) is best of all.

QUESTIONS OF COLOUR

One aspect of the Third Symphony, which Walter and an almost excessively analytical CBS recording bring into focus, is the particular quality of Brahms’s orchestration. This is something you will also find in Fritz Reiner’s exquisitely played 1957 Chicago performance and Herbert von Karajan’s 1961 account with the Vienna Philharmonic, a performance that suggests a more than passing debt by Brahms to Schumann and to the tone-painting of Wagner. Karajan’s three Berlin versions are a good deal less interesting, compromised as they are by the conductor’s almost studied disregard for the symphony’s troubled psychopathology.

A conductor without a dispassionate bone in his body was Sir John Barbirolli. He made two recordings of the Third Symphony, the first in Manchester in 1952, the second in Vienna in 1967; both are memorable, both too little known. The absence of an exposition repeat is more of a problem with the swifter and lighter-toned Hallé performance (which gets off to a rocky start with over-prominent trumpets in bar two). Yet this is wonderful Brahms: trenchant, vital, from the heart. A slowish finale notwithstanding, the later Vienna Philharmonic recording is finer still. Trevor Harvey praised it to the skies in these columns in February 1969. Yet, like the distinguished Boult recording made in 1970, it is a version that has been more honoured in its absence than in its availability.

Barbirolli’s reading was unusual for its swift yet at the same time affecting and finely pointed way with the symphony’s two inner movements (a quality shared with an offering from Sir Thomas Beecham, an infrequent visitor to this particular musical shore, whose otherwise overly fierce 1957 Symphony of the Air performance can be found on YouTube). One episode is of particular importance: the sombre triplet-dominated six-note phrase on clarinet and bassoon which casts its shadow not only over the slow movement but over the finale too. Elgar described the motif’s later appearance as ‘the tragic outcome of a wistful theme’. Is it their exposure to Elgar’s own music that makes British conductors such effective purveyors of the episode’s melancholy, far-off feel?

A DECLINING MARKET

Memorable recordings of the Third Symphony became increasingly scarce in the later years of the 20th century as the old ways of conducting the music were either forgotten or proscribed. Sadly, the fresh interest period practice brought to the symphonies of Beethoven worked less well for those of Brahms. Performance historian Robert Philip wondered whether Roger Norrington knew how the Third generally went. Norrington’s was, he said on Radio 3’s Record Review, ‘an unusually straight performance compared with the disciplined yet highly nuanced performances of Szell or Bruno Walter’. Jonathan Swain, writing in Gramophone, thought it more ‘a trail-blazing performance’ than ‘an interpretation that had had time to mature’. Much was made of the lighter string sound and the more forward winds. But this was nothing new. Such balances are writ large in Klemperer’s stoically splendid 1957 EMI recording.

Mention was also made of the reduced size of the orchestra. In the 1880s, the Vienna Philharmonic, which gave the work its premiere under Hans Richter, was heard alongside Hans von Bülow’s Meiningen Orchestra. Brahms’s friend the critic Eduard Hanslick thought the 45-strong Meiningen Orchestra ‘comparatively weak’, lacking the ‘brilliance and fullness of tone’ of the 90-man Philharmonic. There is evidence that Brahms, too, could be irked by Bülow’s small-scale, over-literal readings, and by the mannerisms he occasionally found it necessary to introduce. How satisfied would Brahms have been, one wonders, with Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s closely managed but oddly tired-sounding 1997 Berlin recording? In 2008, a further period-instrument performance appeared, directed by Sir John Eliot Gardiner. It boasted tinder-dry sonorities and set a new land-speed record for the finale.

The most accomplished Brahms Third of the new century came from Marin Alsop and the LPO in 2005, a long-drawn, dark-hued reading blessed with exquisite phrasing, keen articulation and good rhythm. Sir Simon Rattle’s 2008 recording revived the old Berlin Philharmonic Brahms sound in a performance that went deeper than Karajan’s but which suffered from moments of unwanted calculation. There is nothing of this in Claudio Abbado’s 1989 Berlin recording. This was made in September of that year, barely two months after Karajan’s death and shortly before the players elected Abbado as their chief conductor. It was clearly a meeting of some moment. The Berliners are on peerless form, an asset which Abbado, ever the thoroughbred musician, exploits to remarkable effect in a reading that marries impetus and eloquence in special measure.

Brahms’s Third Symphony is difficult to capture in a single snapshot. The one performance that comes close to being all-encompassing is Furtwängler’s in Berlin in 1949, though the sound is indifferent, the audience occasionally intrusive. Among currently available, single-disc versions, Claudio Abbado’s is a clear first choice. This reading ranks with the best of any era, and there is a visceral quality to the playing which is de rigueur in this symphony. More classically minded Brahmsians should consider Klemperer or, if a single CD is sought, Günter Wand. The best of the rest can generally be found with a little looking. This is a symphony, highly strung and elusive to the touch, which it pays to collect.

RECOMMENDATIONS

BUDGET RICHES:

LPO / Alsop / Naxos 8 557430

Discussing Brahms's Third Symphony is one thing, conducting it is something else. Marin Alsop does both shrewdly, sensitively, perceptively. This is the latest in a distinguished line of LPO Thirds stretching back to Weingartner in 1938.

THE CLASSICIST’S VIEW:

Philharmonia / Klemperer / EMI 562742-2

Born and brought up to Brahms, Klemperer is the most dauntless of the symphony’s classicising interpreters. What on LP was a rather acerbic-sounding recording emerges on CD with greater body and warmth.

THE UNMISSABLE:

BPO / Furtwängler / EMI 565513-2

The sound here is fragile and the audience intrusive, but this is a performance like no other. You may not sleep for nights after hearing it, but you'll be richer and wiser for the experience.

THE TOP CHOICE:

BPO / Abbado / DG 429 765-2GH

This is the finest of the modern versions, a performance that sits well beside classic recordings such as those by Krauss in the 1930s, Walter and Barbirolli in the 60s, and Sanderling in the 70s.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1928 Philadelphia Orch / Stokowski / Biddulph WHL017/18 (8/94R)

1930 VPO / Krauss / Biddulph M WHL052 (6/99)

1932 Concertgebouw Orch / Mengelberg / Andante AN1973-9 (4/33R)

1938 LPO / Weingartner / EMI 764256-2 (9/39R)

1949 BPO / Furtwängler / EMI 565513-2 (2/96R)

1952 Hallé Orch / Barbirolli / Barbirolli Society SJB1020 (5/53R)

1952 Concertgebouw Orch / Szell / Audiophile APL101 561

1952 Philh Orch / Toscanini / Testament SBT3167 (3/00)

1954 BPO / Furtwängler / DG 423 572-2GDO (5/76R)

1955 Philh Orch / Cantelli / Testament SBT1173 (9/56R, 12/99)

1957 Philh Orch / Klemperer / EMI 562742-2 (6/58R)

1957 Chicago SO / Reiner / RCA 09026 61793-2 (12/58R)

1960 Columbia SO / Walter / Sony SMK64471 (2/61R)

1961 VPO / Karajan / Decca 478 2661DOR (9/62R)

1964 Cleveland Orch / Szell / Sony SBK47652 (8/65R, 6/96)

1967 VPO / Barbirolli / Royal ROY6434 (2/69)

1970 LSO / Boult / EMI 769203-2 (2/71R)

1970 Concertgebouw Orch / Haitink / Philips 442 068-2PB4 (3/71R, 9/94)

1972 Dresden Staatskapelle / Sanderling / RCA 74321 30367-2 (10/73R, 1/97)

1975 Hallé / Loughran / EMI 75753-2 (7/76R)

1976 LPO / Jochum / EMI SLS5093 (10/77)

1983 NDR SO / Wand / RCA 88697 71136-2 (2/87R)

1987 Munich PO / Celibidache / EMI 556846-2

1989 BPO / Abbado / DG 429 765-2GH (1/91); 435 683-2GH4

1990 VPO / Giulini / Newton 8802063 (8/91R)

1990 London Classical Plyrs / Norrington / EMI 556118-2 (8/96)

1997 BPO / Harnoncourt / Teldec 0630 13136-2 (11/97); Warner 2564 69004-9

2005 LPO / Alsop / Naxos S 8 557430 (3/07)

2008 Orch Révolutionnaire et Romantique / Gardiner / SDG SDG704 (11/09)

2008 BPO / Rattle / EMI 267254-2 (A/09)

2010 Bavarian Rad SO / Jansons / BR-Klassik 900111 (6/11)

This article originally appeared in Gramophone, April 2012.

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe