Edward Greenfield remembers Leonard Bernstein

Edward Greenfield

Wednesday, January 1, 2014

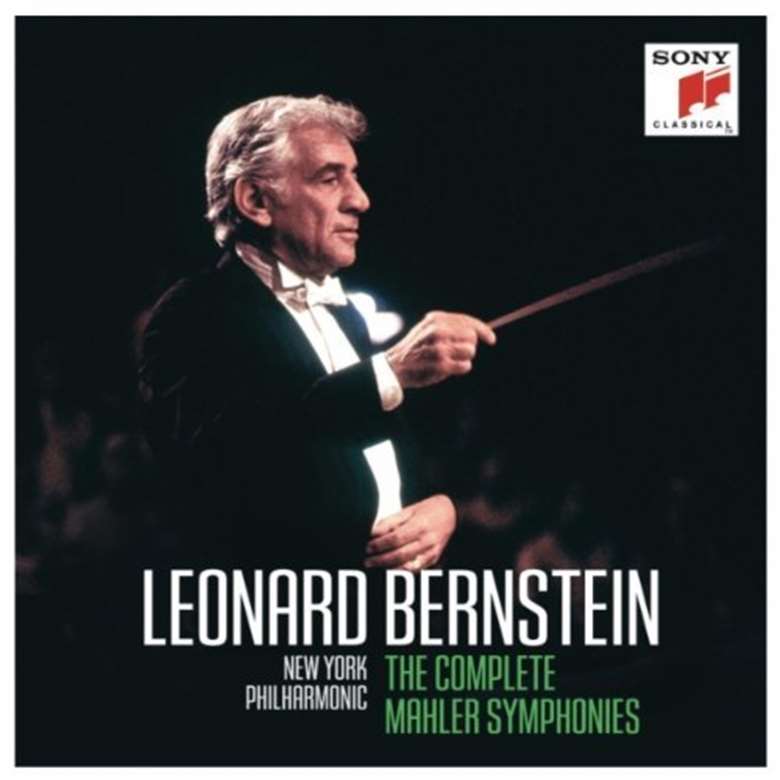

Archive feature from the December 1990 issue written shortly after Leonard Bernstein's death. Edward Greenfield looks back at the life of one the 20th century's leading classical music figures

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter