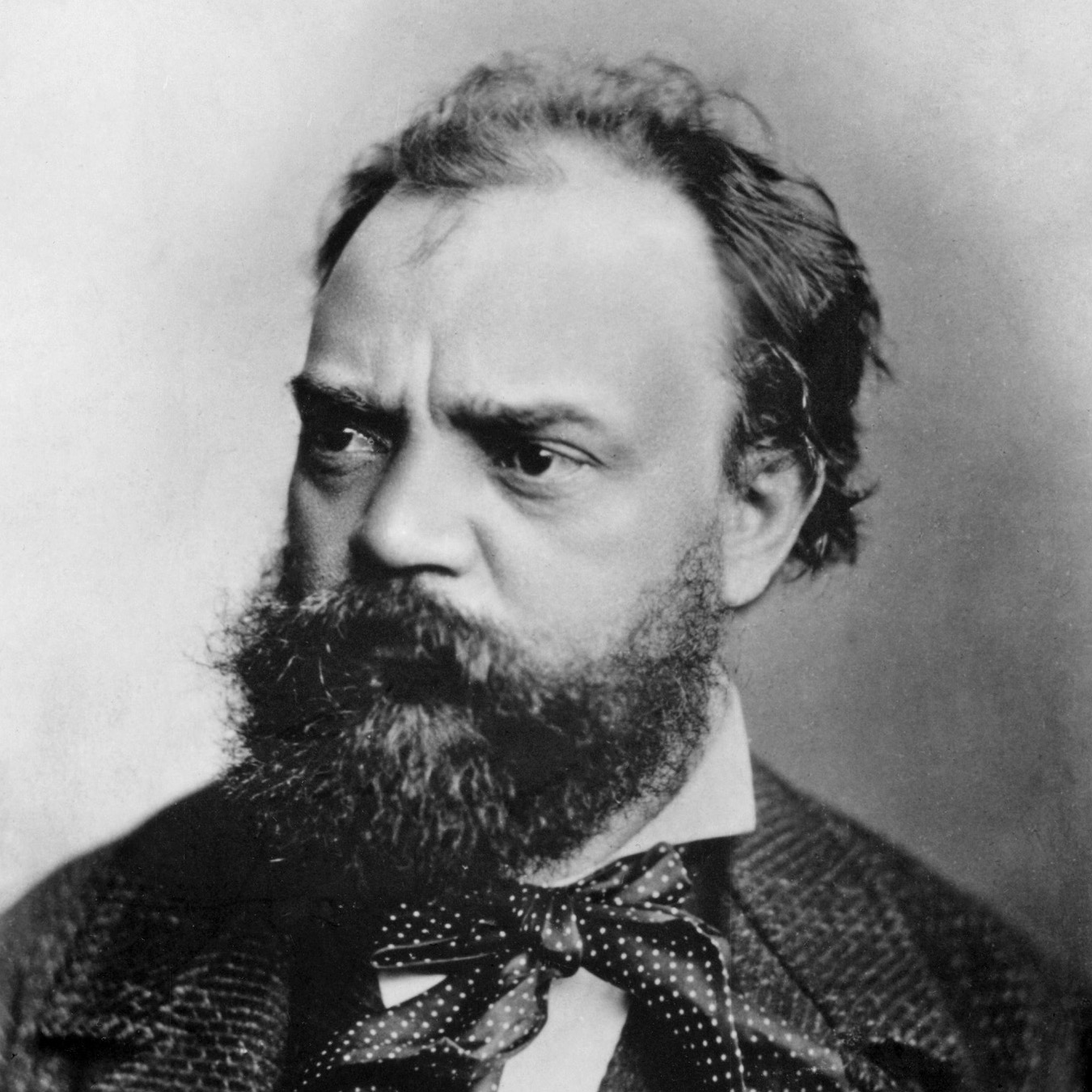

Dvořák

Born: 1841

Died: 1904

Antonín Dvořák

If Smetana was the founding father of Czech music, Dvořák was the one who popularised it. A love of the countryside and nature pervades his work. He himself was noted for his sunny, out-going disposition, qualities that are reflected in his music – no turmoil or neuroticism, no dark, brooding side.

Explore Dvořák’s life and music...

Dvořák’s Fifth Symphony – which recording is best?

Dvořák’s Fifth is the first wholly personal masterwork in his symphonic canon. Andrew Achenbach separates the great performances on disc from the merely good... Read more

Top 15 Dvořák recordings

Dvořák's music has inspired the advocacy of some of the finest musicians, from Rostropovich and Karajan to Kožená and Rattle. Here are 15 of the best Dvořák recordings... Read more

The greatest of all Czech composers, whose best works are among the finest of the second half of the 19th century, recognised internationally and a hero among his countrymen, died impoverished. The violinist Fritz Kreisler went to visit him at his home in 1903 and said the scene recalled something out of La bohème. Dvořák had sold all his music for a pittance and all the money from his tours and stay in America had gone. ‘I had been playing some of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances,’ wrote Kreisler, ‘and visited the old man to pay my respects.

I asked him whether he had nothing further for me to play. “Look through that pile,” said the sick composer, indicating a pile of unorganised papers. “Maybe you can find something.” I did. It was the Humoresque.’ (Now one of Dvořák’s best-known pieces, the Humoresque was transcribed for violin and piano by Kreisler, achieving enormous popularity.)

If his father had had his way, Dvořák would have followed in his footsteps and become a butcher. Instead, his extraordinary musical gifts led him elsewhere, though recognition was a long time coming. He learnt the violin as a child, became a chorister in his native village and played in local orchestras. Financed by an uncle, when Dvořák was 12 he was sent away to study music and learn German. The headmaster of the school, Antonín Liehmann, was an excellent musician who not only taught Dvořák the piano, viola and organ but also gave him a good grounding in music theory.

Throughout the 1860s he was an orchestral violinist and viola player, performing in cafés and theatres, and composing prolifically. He played in a concert of Wagner excerpts conducted by the composer and came under his spell, and later played in the Prague National Theatre Orchestra under the father of Czech music, Smetana. Life was a struggle both financially and creatively. Dvořák lived for music and nothing else but trains. Like Hindemith half a century later, Dvořák was one of music’s great trainspotters, knew all the timetables from the Franz-Josef Station in Prague off by heart and often said that he would have liked to have invented the steam locomotive, ‘one of the highest achievements of the human spirit’.

In 1873 he abandoned the orchestra for the organ loft (St Adalbert’s in Prague), a less demanding job which gave him more time to compose. The same year he married his former pupil, Anna Čermáková. Suddenly, a string of marvellous pieces appeared (including the Serenade for strings), news of his music spread and before five years had elapsed he found himself recognised throughout Europe as a major creative force. What Dvořák had done was to recognise that what he had been writing up till 1873 was derivative, a copy of Wagner, Brahms and other German post-Romantics. As soon as he turned to Czech nationalism and began using the musical character and folk rhythms of his native land, a personal, fresh, distinctive voice emerged. His Symphony No 3 won him a national prize as well as the respect of Brahms (who was on the jury) and the relationship between the two men developed into one of lifelong friendship. Brahms was instrumental in finding a publisher for the younger man’s work and Dvořák went on to win the Austrian State prize four years in succession.

Dvořák’s frequent visits to England during the 1880s spread his fame further – his choral works were eagerly lapped up – and he was awarded many prestigious honours, culminating in 1891 when he was made a professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory, awarded an honorary doctorate by Cambridge University and offered the directorship of the National Conservatory of New York at an annual salary of $15,000. Dvořák moved to the States in 1893, after a string of farewell European tours. A combination of homesickness and the discovery of American indigenous folk music combined to inspire a string of masterpieces, including the ‘New World’ Symphony, the Cello Concerto and the ‘American’ String Quartet.

On returning to Prague, he resumed his professorship, was made director of the Conservatory in 1901 and appointed a life member of the Austrian House of Lords, the first musician to be so honoured. During this final period, Dvořák turned to writing symphonic poems based on old Czech legends and, especially, operas – including the only one which remains in today’s repertoire, Rusalka. Though his last months were clouded by the fiasco of his new opera Armida (he died of an apoplectic stroke six weeks after its premiere), his death was marked by a national day of mourning.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.