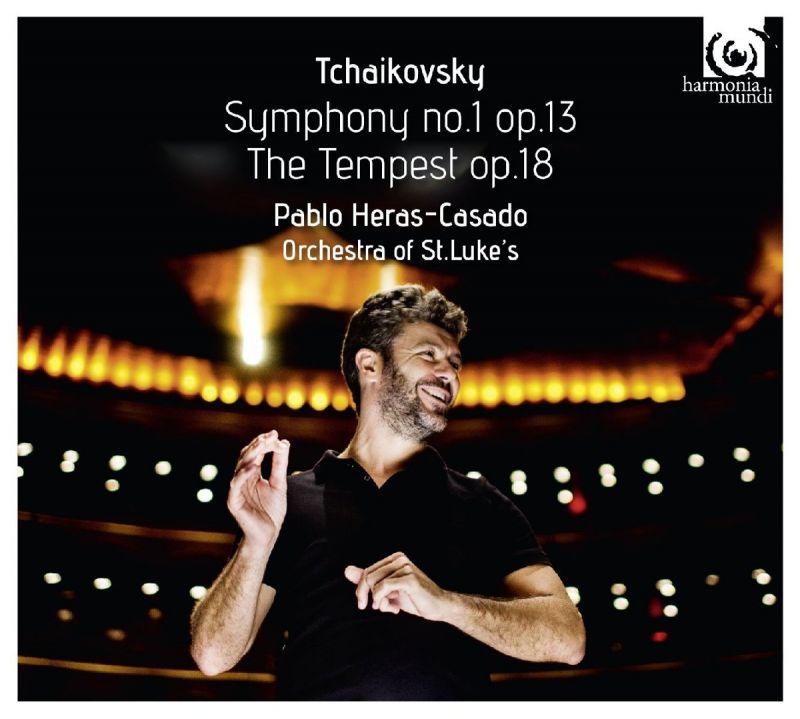

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No 1. The Tempest

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Magazine Review Date: 02/2017

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 68

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: HMC90 2220

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 1, 'Winter Daydreams' |

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Composer

Pablo Heras-Casado, Conductor Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Composer St Luke's Orchestra |

| (The) Tempest |

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Composer

Pablo Heras-Casado, Conductor Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Composer St Luke's Orchestra |

Author: Peter Quantrill

In their different ways, all these conductors convey the sense of a distinctively Russian composer taking his first steps, some confident, some faltering, in a genre hitherto foreign to his tradition. The context of its time, however, the 1866-ness of the piece, is more elusive, and here Heras-Casado brings a special alertness to the pointing of phrase and building of form that makes sense of what the composer’s brother Modest tells us about the works’s difficult birth, a decade before Brahms finally produced his own First Symphony. For astutely chosen exemplars, Tchaikovsky would play through the Italian Symphony of Mendelssohn and the Spring Symphony of Schumann.

This is hardly the first recording to bring Mendelssohnian deftness to the Scherzo and the waltz-Trio (and to imagine the influence working spookily in reverse, listen to the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang in Heras-Casado’s recording with the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra), but the thinning out of the Scherzo to a few solo voices – like guests drifting away from the Act 3 ball of Eugene Onegin – is so characteristic of both composers. It is achieved here with an intimacy that comes naturally to chamber orchestras, rather than as one of those sudden hushes implied by the kind of ‘now, children, let’s be quiet as mice’ gestures sometimes seen on the podium, perhaps more for the audience than the orchestra’s benefit. (At this point and others, the most recent rival recording, of the RLPO and Vasily Petrenko – Onyx, 8/16 – is neatly done but generic.) And Schumann? Try the barely contained but uninflated exuberance of the first movement’s main statements in the brass.

The nearest interpretative point of comparison, then, is with Jurowski (LPO, 11/09), who moves with no less flair between period and big symphonic orchestras. Nonetheless, the Orchestra of St Luke’s is a Classically sized and inclined ensemble. The difference in scale tells not in lack of impact but the reverse. When trombones and bass drum make telling entrances in the outer movements, you know about it. The finale’s string fugato is that crucial degree more sinewy – and convincing – when taken on the wing by musicians for whom Mozart rather than Mahler is daily bread. Unlike Sir Roger Norrington’s Pathétique, this historically sensitive approach does not entail a stripped-pine tone quality.

With a flexible but coherent momentum, Heras-Casado takes his time to draw out the shy second theme of the symphony’s Adagio cantabile, which steals in with sensuous reticence. His boldest step is to lend Brucknerian nobility to the theme’s return on full horns at the movement’s climax: it’s much less crude than any other version I’ve heard and brings a new pathos to the coda.

There is throughout the symphony a continence of rhetoric that may appeal to anyone not unshakably attached to Golovanov, Svetlanov and their kin. Even the finale’s efficient rather than inspired episodes of contrapuntal imitation are elevated to bring the symphony to a well earned point of arrival worthy of comparison with Jurowski and Karajan. The voltage may be lower in The Tempest, but then Heras-Casado’s approach is not to mask the structural cracks in the piece with greasepaint. He attends carefully to each picturesque episode and naturalistic detail, bringing Liszt’s Les préludes to mind more than Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. In fact the storm itself lacks nothing in vehemence, and as in the symphony’s first movement, the synchronicity of motion and expressive intent within the string body projects the music more strongly than a larger, more diffuse ensemble (just as a choir of 16 often sounds louder than one of 60). The strange, unison string recitative before the coda (much borrowed by Shostakovich, almost directly so in the Fifth Symphony) is not simply hurled out but introduces a note of properly Shakespearean ambiguity before Prospero’s chorale and the Impressionist seascape take over.

On the heels of Bychkov’s fascinating Pathétique and Barenboim’s latest, positively cinematic take on the orchestral texture of the Violin Concerto, Heras-Casado has me wondering about a new wave of Tchaikovsky performance: shunning hysteria and crocodile tears, painting pictures, telling stories.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.