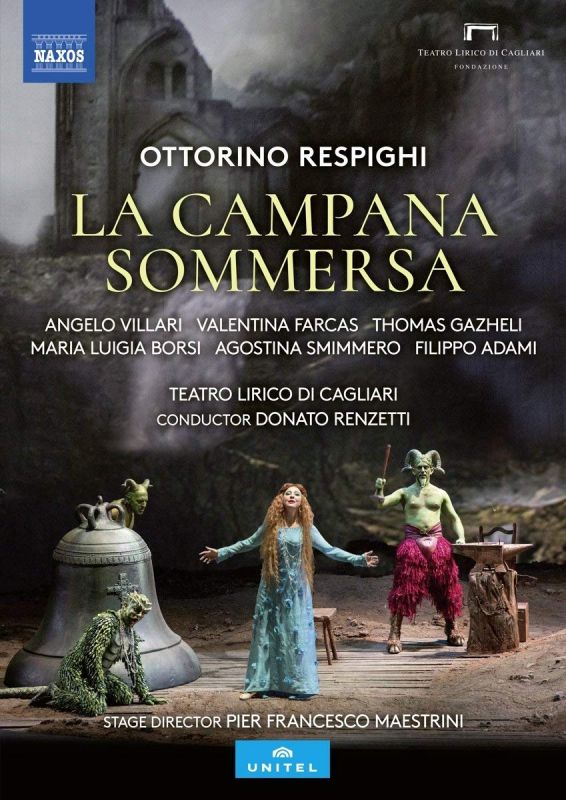

RESPIGHI La campana sommersa (Renzetti)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ottorino Respighi

Genre:

Opera

Label: Naxos

Magazine Review Date: 09/2018

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 140

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 2 110571

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| La campana sommersa |

Ottorino Respighi, Composer

Agostina Smimmero, Old Witch, Mezzo soprano Angelo Villari, Enrico, Tenor Cagliari Teatro Lirico Chorus Cagliari Teatro Lirico Orchestra Children’s Choir of the GP da Palestrina Conservatory, Cagliari Dario Russo, Priest, Bass Donato Renzetti Filippo Adami, Faun, Tenor Francesca Paola Geretto, Second Elf, Soprano Maria Luigia Borsi, Magda, Soprano Martina Bortolotti, First Elf, Soprano Mauro Secci, Barber, Tenor Nicola Ebau, Schoolmaster, Baritone Olesya Berman Chuprinova, Third Elf, Mezzo soprano Ottorino Respighi, Composer Thomas Gazheli, Ondino, Baritone Valentina Farcas, Rautendelein, Soprano |

Author: Tim Ashley

Its source is Gerhart Hauptmann’s 1896 play Die versunkene Glocke, a Symbolist fairy tale, much indebted to Maeterlinck and Wagner. The Undine legend lurks behind the doomed central relationship between the elf Rautendelein and the bell-maker Heinrich (Enrico in Claudio Guastalla’s libretto), though Hauptmann expands his material into an overloaded parable about humanity’s desecration of nature and the perilous nature of creativity itself.

The sunken bell of the title is Enrico’s masterwork, which has slipped from its trestle before it can be raised or rung and fallen into a lake, wounding its maker in the process. Straying into one of those mysterious forests with which Symbolist literature abounds, Enrico encounters Rautendelein sitting, like Mélisande, by a well. Falling in love with him, she restores him to health, then becomes the inspiration for his unhinged attempt to build a temple to a new religion that links Christ with Balder (the Teutonic god of light), forcing the spirits of nature, Alberich-like, into slave labour in the process, and eventually driving his neglected wife Magda to suicide. At this point, the sunken bell begins to toll from the depths of the lake, heralding both Enrico’s death and the gradual restoration of the natural order, to which the sorrowful Rautendelein returns.

According to Elsa Respighi, the opera’s composition, begun in 1925, entailed both ‘joyous exaltation and desperate crises’, and there can be little doubt that her husband lavished tremendous care on it. Ravishing string and woodwind textures evoke the natural world, in contrast to the baleful sounds, all low strings and growling brass, that indicate the invasive presence of humanity. Rearing ostinatos suggest Enrico’s fanaticism, and his bells toll in eerie imitation of their counterparts in Boris Godunov. There’s some exquisite writing for Rautendelein, a coloratura soprano, and her Rhinemaiden-ish trio of attendant Elves, while Enrico is an angst-ridden dramatic tenor, not unlike Otello. Beautiful though it is, though, the score fails to rescue the libretto from the symbolic weight under which it repeatedly buckles and the characters remain ciphers with whom it is almost impossible to empathise.

The Cagliari performance arouses mixed feelings, too. There are moments of sinister magic in Maestrini’s staging, which makes telling use of video, so that we see Enrico’s bell crash spectacularly into the lake and witness Magda’s Ophelia-like suicide, which Respighi and Guastalla kept offstage. Under Donato Renzetti, the orchestra sounds gorgeous, though the singing is uneven. Valentina Farcas, her coloratura wonderfully precise, makes an excellent Rautendelein and there are strong performances from Filippo Adami’s libidinous Faun, Thomas Ghazeli’s reptilian Ondino and Agostina Smimmero as the Witch, who deplores Rautendelein’s misguided fondness for mankind. Angelo Villari’s Enrico sounds handsome but strays off pitch in moments of anguish, however, while Maria Luigia Borsi’s Magda is squally throughout. The accompanying booklet, meanwhile, contains scholarly essays on Respighi’s career and the opera’s history but doesn’t provide a synopsis, which is deeply regrettable.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.