PROKOFIEV Semyon Kotko

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Sergey Prokofiev

Genre:

Opera

Label: Mariinsky

Magazine Review Date: 10/2016

Media Format: Blu-ray

Media Runtime: 148

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: MAR0592

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Semyon Kotko |

Sergey Prokofiev, Composer

Andrei Popov, Klembovsky, Tenor Evgeny Nikitin, Remeniuk, Bass-baritone Gennady Bezzubenkov, Tkachenko, Bass Grigory Karasev, Ivasenko, Bass Lyubov Sokolova, Semyon’s Mother, Mezzo soprano Mariinsky Chorus Mariinsky Orchestra Nadezhda Vassilieva, Khivrya, Mezzo soprano Olga Sergeeva, Lyubka, Soprano Roman Burdenko, Tsaryov, Baritone Sergey Prokofiev, Composer Stanislav Leontyev, Mikola, Tenor Tatiana Pavlovskaya, Sofya, Soprano Valery Gergiev, Conductor Varvara Solovyova, Frosya, Mezzo soprano Viktor Lutsyuk, Semyon Kotko, Tenor |

Author: David Gutman

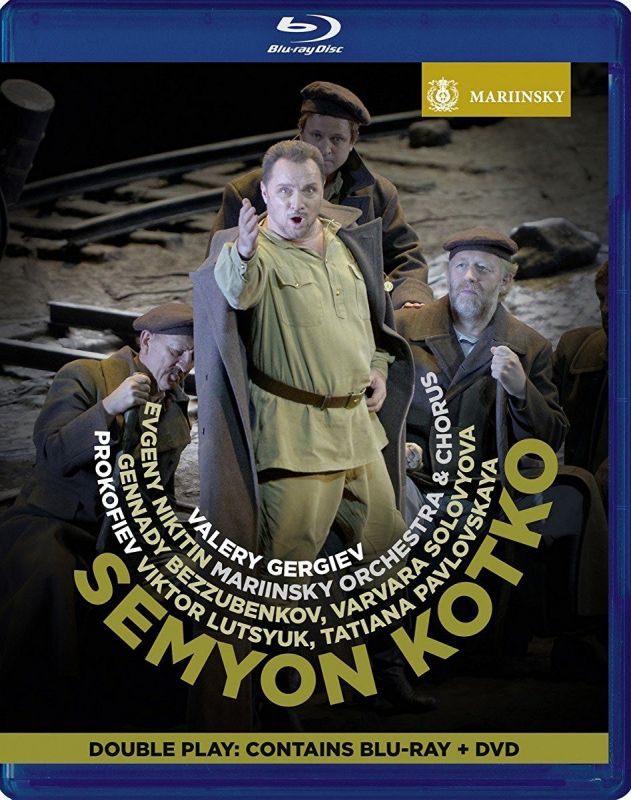

A serial prize-winner in its day, the non-realistic production by Yuri Alexandrov (set amid industrial debris by designer Semyon Pastukh) still looks well give or take some Pythonish stage movement. That said, it’s obvious why we haven’t heard more of the piece. This is Prokofiev’s most overtly class-conscious opera, also intended to exalt the struggle of ordinary Russians against invading Germans, to affirm his own loyalty to the Soviet regime and to improve the lot of its ideologically beleaguered designated director. Instead of which the Terror claimed Vsevolod Meyerhold, Russia signed the Nazi-Soviet pact and Semyon Kotko merely limped on to the stage with obligatory changes imposed. While Act 4 contains a setting of Taras Shevchenko’s ‘Testament’, that Ukrainian national poem is hijacked by the chorus of Communist partisans. It’s an awkward ideological stew that can still cause problems. In August 2016 controversy raged over the scheduling of an extract as part of Kiev’s independence day celebrations.

If the work’s take on Ukrainian politics might better suit the Donetsk People’s Republic, the surprise is that the musical content is not more brutally simplified. Working with Odessa-born writer and Red Army veteran Valentin Katayev in 1938 39, Prokofiev refused to make a ‘number opera’ of the former’s novella I am a Son of the Working People, preferring to carry the story forwards using naturalistic dialogue that rides over accessible melodic ideas allocated to the orchestra. In the wake of Alexander Nevsky, cinematic continuity trumps operatic convention. Applause is heard only at the very end and after Act 3, where Prokofiev adopts a more challenging expressionist manner. Here the relatively marginal character of Lyubka takes centre stage, driven mad by the torching of her village, the execution of her beloved and the atrocities of the invaders. Her endlessly repeated six-note cry of anguish is eventually taken up by the entire chorus, and the surrealistic staging, by no means confining us to 1918, pulls no punches. This could be any senseless apocalypse of warring peoples.

One controversial aspect of the production has been the decision to poke fun at the opera’s closing celebration of socialist realist nirvana: the chorus strike stylised poses clad in ‘Maoist’ grey and equipped with not-so-little red books. Satire was not the composer’s intention (nor could it be in the circumstances), yet it’s difficult to see what else might work today even when, as at the Mariinsky, part of Act 5 is cut. Gergiev’s pacing remains brisk. Mikhail Zhukov’s pioneering 1960 version (Chandos, 5/03), being statelier, gave the music a different emphasis. Rushed or not, there’s a characterful performance from Gennady Bezzubenkov as the villainous ‘kulak’ Tkachenko, while Viktor Lutsyuk, although physically mature for Kotko, still comes across as credibly strong and caring. Evgeny Nikitin is luxury casting as the inescapably one-dimensional Party man, Remeniuk.

Presentation is less opulent than might have been expected for such a unique project. The accompanying booklet offers no index points and reads almost as oddly as the subtitler’s attempts at comic book German and colloquial English. Nor is the filming beyond reproach. There are continuity problems with Sofya’s shawl in Act 2 and a predilection for woozy outsize close-ups. The young video director Anna Matison, a real talent, is conspicuously under-resourced. Unusually, the opening titles are run over the instrumental preamble of the opera itself, the band never seen. Even Gergiev himself is glimpsed only at the very end taking his curtain call. Indispensable nonetheless.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.