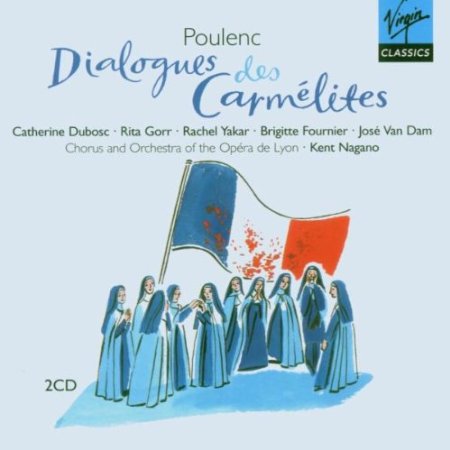

Poulenc Les Dialogues des Carmelites

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Francis Poulenc

Genre:

Opera

Label: Classics

Magazine Review Date: 9/1992

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 759227-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (Les) Dialogues des Carmélites |

Francis Poulenc, Composer

Brigitte Fournier, Soeur Constance, Soprano Catherine Dubosc, Blanche de La Force, Soprano Francis Poulenc, Composer François Le Roux, Le Geôlier, Tenor Jean-Luc Viala, Chevalier de La Force, Tenor José Van Dam, Marquis de La Force, Tenor Kent Nagano, Conductor Lyon Opera Chorus Lyon Opera Orchestra Martine Dupuy, Mère Marie, Alto Michel Sénéchal, L'Aumônier, Tenor Rachel Yakar, Madame Lidoine, Soprano Rita Gorr, Madame de Croissy, Soprano |

Author: Alan Blyth

Kent Nagano and his Lyon forces may well follow their Gramophone Award-winning success of 1990—The love for three oranges—with another for this dedicated achievement. Once more the recording was made after a stage production in their home house. In this case they are performing one of only half a dozen or so great operas written since the war (most of the rest are by Britten or Tippett). Poulenc's masterpiece has already stood the test of 35 years; if it continues to be interpreted as lovingly as here, it may well become a repertory piece in the future. Its only previous recording (EMI 1958) followed the first performances in France. That was until recently available on CD (7/88) but, as with so many other irreplaceable discs in their catalogue, EMI have already capriciously deleted it. What a way for a supposedly responsible company to behave before its store of treasure!

Pierre Dervaux, who died earlier this year, was the conductor there and Nagano has very sensibly followed his predecessor's authoritative reading, one that discloses the piece's interior beauty and exterior skill in depicting the world of the Carmelite order as it faces up to the trials and tribulations of the French Revolution. As Roger Nichols writes in his comprehensive introduction to the new set, the composer succeeded in articulating the predicament of ''fairly ordinary women caught up in an extraordinary destiny''. He did so in music that depends for its unity on recurring motifs and on a setting of the text that leans heavily on Debussy's and his own song-writing idioms: some of the solos could almost be abstracted as songs in themselves. Over and above the technical achievement, Poulenc evokes a convincing sound-world of its own (a sine qua non for any great opera) and makes his audience believe, as he obviously did, in its characters, in their everyday martyrdom and what leads to it.

Nagano has unerringly responded to its sombre, elevated mood, and also realized the useful contrast provided, in just the right places, of male voices. Only once or twice, as for instance in the scene where Blanche's brother tries to persuade her to leave her retreat for the sake of her own safety, did I feel that Nagano missed an extra touch of urgency achieved by Dervaux, but that may have something to do with the old bugbear among modern producers of putting too much space around voices and instruments thus losing the immediacy that used to be achieved by less sophisticated means.

I was frankly astonished—and pleased—to find that the Francophone singers here were virtually on a par with their renowned predecessors. As is a tradition in this piece, a former interpreter of one of the younger characters here becomes the Old Prioress; thus Rita Gorr, Dervaux's Mere Marie, is here Madame de Croissy, and she projects the ailing woman's final agonies with superb intensity and a voice little touched by time, except at the top. The unyielding Mere Marie is here taken by that underrated, unfailingly musical mezzo, Martine Dupuy, singing with firm tone and magisterial authority rightly tempered by a good heart. Crespin, more recently an Old Prioress at Covent Garden, was Dervaux's Madame Lidoine, the new Prioress. For Nagano, Yakar almost but not quite equals her predecessor's exceptionally eloquent assumption, singing her two extended solos with refined and unaffected diction.

More important than any of these is Sister Blanche. The opera is as much about her personal torments and eventual saving as anything else. A neurotic, fantasizing girl, she seeks comfort in the convent but never quite comes to terms with its rigours of mind and body. Poulenc wrote it for Denise Duval, who took the role for Dervaux. Happily Catherine Dubosc matches Duval in tone and accent, and goes one better in refined phrasing, as at ''la pauvre petite victime de Sa Divine Majeste'' in Act 2. Only a singer who has taken the role on stage can provide that kind of conviction. As her light-hearted companion, Sister Constance, Brigitte Fournier is delightfully airy and eager—just right.

The male characters have been cast, to say the least, from strength. Van Dam launches the opera strongly with his purposeful, fatherly Marquis and Viala quite avoids the bleating of his EMI counterpart as the Chevalier, Blanche's brother. Veteran Michel Senechal is ideally cast as the sympathetic Chaplain and Le Roux is suitably implacable as the accusing Gaoler.

The work is given absolutely complete here (the EMI employs the four optional cuts), including the short interlude of melodrama before the finale. There is a judicious attempt at imitating stage action, and a well-balanced distribution of the characters. In spite of my earlier stricture, this highly recommendable version has, of course, a far wider range of dynamics than its EMI predecessor. Anyone interested in the best of twentieth-century opera and—more important—wants to share in a deeply moving experience should have this set.'

Pierre Dervaux, who died earlier this year, was the conductor there and Nagano has very sensibly followed his predecessor's authoritative reading, one that discloses the piece's interior beauty and exterior skill in depicting the world of the Carmelite order as it faces up to the trials and tribulations of the French Revolution. As Roger Nichols writes in his comprehensive introduction to the new set, the composer succeeded in articulating the predicament of ''fairly ordinary women caught up in an extraordinary destiny''. He did so in music that depends for its unity on recurring motifs and on a setting of the text that leans heavily on Debussy's and his own song-writing idioms: some of the solos could almost be abstracted as songs in themselves. Over and above the technical achievement, Poulenc evokes a convincing sound-world of its own (a sine qua non for any great opera) and makes his audience believe, as he obviously did, in its characters, in their everyday martyrdom and what leads to it.

Nagano has unerringly responded to its sombre, elevated mood, and also realized the useful contrast provided, in just the right places, of male voices. Only once or twice, as for instance in the scene where Blanche's brother tries to persuade her to leave her retreat for the sake of her own safety, did I feel that Nagano missed an extra touch of urgency achieved by Dervaux, but that may have something to do with the old bugbear among modern producers of putting too much space around voices and instruments thus losing the immediacy that used to be achieved by less sophisticated means.

I was frankly astonished—and pleased—to find that the Francophone singers here were virtually on a par with their renowned predecessors. As is a tradition in this piece, a former interpreter of one of the younger characters here becomes the Old Prioress; thus Rita Gorr, Dervaux's Mere Marie, is here Madame de Croissy, and she projects the ailing woman's final agonies with superb intensity and a voice little touched by time, except at the top. The unyielding Mere Marie is here taken by that underrated, unfailingly musical mezzo, Martine Dupuy, singing with firm tone and magisterial authority rightly tempered by a good heart. Crespin, more recently an Old Prioress at Covent Garden, was Dervaux's Madame Lidoine, the new Prioress. For Nagano, Yakar almost but not quite equals her predecessor's exceptionally eloquent assumption, singing her two extended solos with refined and unaffected diction.

More important than any of these is Sister Blanche. The opera is as much about her personal torments and eventual saving as anything else. A neurotic, fantasizing girl, she seeks comfort in the convent but never quite comes to terms with its rigours of mind and body. Poulenc wrote it for Denise Duval, who took the role for Dervaux. Happily Catherine Dubosc matches Duval in tone and accent, and goes one better in refined phrasing, as at ''la pauvre petite victime de Sa Divine Majeste'' in Act 2. Only a singer who has taken the role on stage can provide that kind of conviction. As her light-hearted companion, Sister Constance, Brigitte Fournier is delightfully airy and eager—just right.

The male characters have been cast, to say the least, from strength. Van Dam launches the opera strongly with his purposeful, fatherly Marquis and Viala quite avoids the bleating of his EMI counterpart as the Chevalier, Blanche's brother. Veteran Michel Senechal is ideally cast as the sympathetic Chaplain and Le Roux is suitably implacable as the accusing Gaoler.

The work is given absolutely complete here (the EMI employs the four optional cuts), including the short interlude of melodrama before the finale. There is a judicious attempt at imitating stage action, and a well-balanced distribution of the characters. In spite of my earlier stricture, this highly recommendable version has, of course, a far wider range of dynamics than its EMI predecessor. Anyone interested in the best of twentieth-century opera and—more important—wants to share in a deeply moving experience should have this set.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.