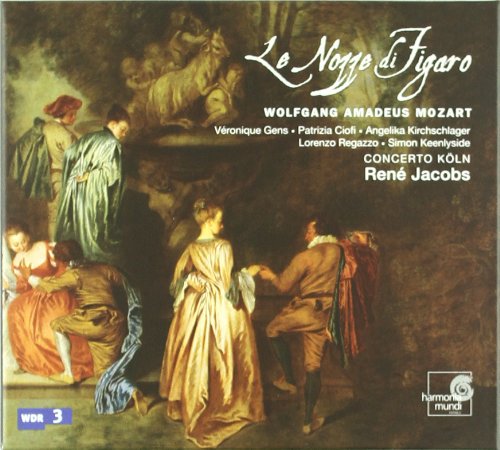

Mozart (Le) Nozze di Figaro

An excellent cast, though this refreshing treatment of Figaro won’t be to all tastes

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Genre:

Opera

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Magazine Review Date: 5/2004

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 172

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: HMC90 1818/20

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (Le) nozze di Figaro, '(The) Marriage of Figaro' |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Composer

Angelika Kirchschlager, Cherubino, Mezzo soprano Antonio Abete, Bartolo; Antonio, Bass Collegium Vocale Concerto Köln Kobie van Rensburg, Don Basilio; Don Curzio, Tenor Lorenzo Regazzo, Figaro, Bass Marie McLaughlin, Marcellina, Soprano Nuria Rial, Barbarina, Soprano Patrizia Ciofi, Susanna, Soprano René Jacobs, Conductor Simon Keenlyside, Count Almaviva, Baritone Véronique Gens, Countess Almaviva, Soprano Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Composer |

Author: Stanley Sadie

René Jacobs always brings new ideas to the operas he conducts, and even to a work as familiar as Figaro he adds something of his own. First of all – and this will be obvious to listeners from the opening bars – he offers an orchestral balance quite unlike what we are used to. Those who specially relish a Karajan or a Solti will hardly recognise the work, with its strongly wind-biased orchestral balance: you simply do not hear the violins as the ‘main line’ of the music. An excellent corrective to a tradition that was untrue to Mozart, to be sure, but possibly the pendulum has swung a little too far. For my own part, I rather enjoy it, although there are some string passages that almost get lost.

Jacobs is freer over tempo than most conductors. Sometimes, perhaps most conspicuously in the Act 1 trio where Cherubino is uncovered, the Count’s authoritarian pronouncements are given further weight by a faster tempo: it gives them extra decisiveness, but creates an attendant problem as the music then has to slow down. There are other examples of such flexibility, sometimes a shade disconcerting (mainly, perhaps, because we aren’t used to it), but always with good dramatic point. The Count’s duet with Susanna in Act 3 is one example: the little hesitancies enhanced and pointed up, if perhaps with some loss in energy and momentum. Generally speaking, tempi are on the quick side of normal, notably in the earlier parts of the Act 2 finale; but Jacobs is willing to hold back, too, for example in the Susanna-Marcellina duet, in the fandango (very nicely poised), and in the G major music at the dénouement where the Count begs forgiveness – this, to my mind, is overdone, becoming merely solemn and even slightly dull. I’m not always quite convinced that Jacobs’s ideas and instincts are truly Mozartian.

Over the years, Gramophone readers may have become bored with my repeated advocacy of the use of proper appoggiaturas. There are lots of them here, but quite a few seem to me misguided, or misapplied, and don’t sit comfortably (as they nearly always do in Arnold Östman’s recording). It isn’t perhaps unreasonable to think that Mozart may sometimes actually have wanted a pair of repeated notes (in that Act 1 trio, for example). I also find myself uncomfortable with the ‘creative’ fortepiano continuo playing, which often draws attention to itself unduly at the expense of the voices – including, sometimes, in the lyrical music, where the piano supplements (and sometimes confuses) the texture, and in the recitatives where the player too cleverly echoes or pre-echoes phrases from the arias. And there are some oddities in the cello continuo playing, too, more apt to Monteverdi than to Mozart. But the idea of using vocal ornamentation from sources of Mozart’s own time, or just after, at the singers’ choice, is a happy and very successful one.

The cast is excellent. Véronique Gens offers a beautifully natural, shapely ‘Porgi amor’ and a passionate and spirited ‘Dove sono’ (with the piano rampant near the end). The laughter in Patrizia Ciofi’s voice is delightful when she is dressing up Cherubino, and she has space in ‘Deh vieni’ for a touchingly expressive performance. Then there is Angelika Kirschlager’s Cherubino, alive and urgent in ‘Non so più’, every little phrase neatly moulded. Lorenzo Regazzo offers a strong Figaro, with a wide range of voice – angry and determined in ‘Se vuol ballare’, nicely rhythmic with some softer colours in ‘Non più andrai’, and pain and bitterness in ‘Aprite’. The Count of Simon Keenlyside is powerful, menacing, lean and dark in tone. Marie McLaughlin sings Marcellina with unusual distinction. As in Mozart’s performances, the male comprimario parts are doubled, Bartolo/Antonio and Basilio/Curzio, and following the precedent of the original singer, Michael Kelly, the Curzio has a stammer – Mozart initially objected to that, but Kelly (or so he says in his reminiscences) won him over.

Strongly cast, imaginatively directed: it’s a Figaro well worth hearing, though I wouldn’t suggest that it challenges the best in the catalogue. And which is that? Well, I’m not really sure, but I get as much pleasure from the Östman version made in Drottningholm by the much lamented Peter Wadland as any.

Jacobs is freer over tempo than most conductors. Sometimes, perhaps most conspicuously in the Act 1 trio where Cherubino is uncovered, the Count’s authoritarian pronouncements are given further weight by a faster tempo: it gives them extra decisiveness, but creates an attendant problem as the music then has to slow down. There are other examples of such flexibility, sometimes a shade disconcerting (mainly, perhaps, because we aren’t used to it), but always with good dramatic point. The Count’s duet with Susanna in Act 3 is one example: the little hesitancies enhanced and pointed up, if perhaps with some loss in energy and momentum. Generally speaking, tempi are on the quick side of normal, notably in the earlier parts of the Act 2 finale; but Jacobs is willing to hold back, too, for example in the Susanna-Marcellina duet, in the fandango (very nicely poised), and in the G major music at the dénouement where the Count begs forgiveness – this, to my mind, is overdone, becoming merely solemn and even slightly dull. I’m not always quite convinced that Jacobs’s ideas and instincts are truly Mozartian.

Over the years, Gramophone readers may have become bored with my repeated advocacy of the use of proper appoggiaturas. There are lots of them here, but quite a few seem to me misguided, or misapplied, and don’t sit comfortably (as they nearly always do in Arnold Östman’s recording). It isn’t perhaps unreasonable to think that Mozart may sometimes actually have wanted a pair of repeated notes (in that Act 1 trio, for example). I also find myself uncomfortable with the ‘creative’ fortepiano continuo playing, which often draws attention to itself unduly at the expense of the voices – including, sometimes, in the lyrical music, where the piano supplements (and sometimes confuses) the texture, and in the recitatives where the player too cleverly echoes or pre-echoes phrases from the arias. And there are some oddities in the cello continuo playing, too, more apt to Monteverdi than to Mozart. But the idea of using vocal ornamentation from sources of Mozart’s own time, or just after, at the singers’ choice, is a happy and very successful one.

The cast is excellent. Véronique Gens offers a beautifully natural, shapely ‘Porgi amor’ and a passionate and spirited ‘Dove sono’ (with the piano rampant near the end). The laughter in Patrizia Ciofi’s voice is delightful when she is dressing up Cherubino, and she has space in ‘Deh vieni’ for a touchingly expressive performance. Then there is Angelika Kirschlager’s Cherubino, alive and urgent in ‘Non so più’, every little phrase neatly moulded. Lorenzo Regazzo offers a strong Figaro, with a wide range of voice – angry and determined in ‘Se vuol ballare’, nicely rhythmic with some softer colours in ‘Non più andrai’, and pain and bitterness in ‘Aprite’. The Count of Simon Keenlyside is powerful, menacing, lean and dark in tone. Marie McLaughlin sings Marcellina with unusual distinction. As in Mozart’s performances, the male comprimario parts are doubled, Bartolo/Antonio and Basilio/Curzio, and following the precedent of the original singer, Michael Kelly, the Curzio has a stammer – Mozart initially objected to that, but Kelly (or so he says in his reminiscences) won him over.

Strongly cast, imaginatively directed: it’s a Figaro well worth hearing, though I wouldn’t suggest that it challenges the best in the catalogue. And which is that? Well, I’m not really sure, but I get as much pleasure from the Östman version made in Drottningholm by the much lamented Peter Wadland as any.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.