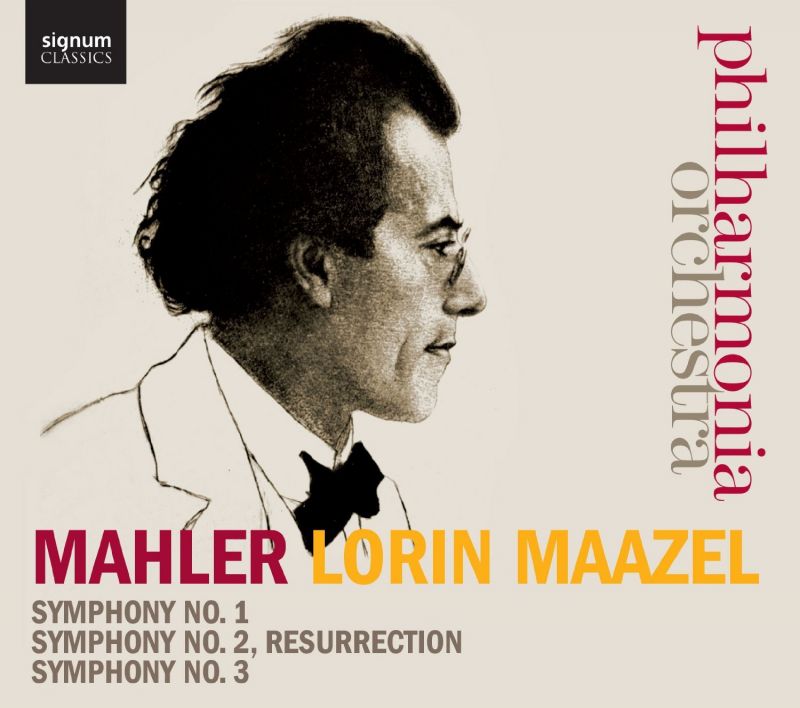

MAHLER Symphonies 1-3

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Gustav Mahler, Lorin Maazel

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Signum Classics

Magazine Review Date: 03/2014

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: SIGCD360

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 1 |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

Gustav Mahler, Composer Lorin Maazel, Composer Philharmonia Orchestra |

| Symphony No. 2, 'Resurrection' |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

BBC Symphony Chorus Gustav Mahler, Composer Lorin Maazel, Composer Michelle DeYoung, Mezzo soprano Philharmonia Orchestra Sally Matthews, Soprano |

| Symphony No. 3 |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

Gustav Mahler, Composer Lorin Maazel, Composer Philharmonia Orchestra Philharmonia Voices Sarah Connolly, Mezzo soprano Tiffin School Boys' Choir |

Author:

The downtrodden quiet marching episode at around 8'57" into the first movement of the Resurrection has more tension in London (a little more breathing space too, as does the huge finale), the terror-filled, brass dominated return of the opening alarm (12'50"), greater shock value. The Andante’s opening has a subtler lilt as shared among the Philharmonia strings but the sheer classiness of the Viennese string sound brings with it a uniquely seductive appeal that for some may well swing the balance in its favour. Then again, the Philharmonia Scherzo has an impishness that the Viennese alternative lacks (sample the opening). When it comes to ‘Urlicht’, for all the warmth and inwardness that Michelle DeYoung brings to this sublime song, Jessye Norman in Vienna, with her veiled tone and tighter vibrato, delivers a performance of surpassing beauty that DeYoung doesn’t quite match, at least not on this occasion. But then there’s the finale, a canvas as vast as it’s rich in perspectives. Maazel’s approach is fairly consistent in both versions, Sally Matthews in London every bit as affecting as Eva Marton in Vienna. As a performance, it works well; though, to be truthful, once heard complete, I came away less moved than I have been under other conductors. Maazel has as fine an ear as any maestro on this planet but somehow, unless I’m missing something, the uplifting denouement of this symphony remains strangely earthbound.

Scale is a crucial attribute of the Third Symphony, and you need only sample this new version of the opening, replete with thunderous bass drum thwacks, to realise that its predecessor packs less of a wallop. The mock military march episode at 22'58", with its squealing woodwinds, is virtually identical tempo-wise to the Vienna performance but Signum’s recording achieves a fuller canvas, with a more clearly defined bass drum at the end. I prefer the freer, swifter tempo for the balletic Scherzando second movement (the Vienna version sounds a mite plodding), though the second section is similarly sedate. The one disappointment here is that the posthorn solo, beautifully played though it is, sounds as if set within the orchestra rather than somewhere offstage, as is the case – to magical effect – on the VPO recording. Mezzo Sarah Connolly is a fair match for Agnes Baltsa in the Nietzsche fourth movement and it’s interesting how Maazel has his oboist play with eerie-sounding glissandos, something he didn’t call for from his Viennese counterpart. The paean to love that concludes the work ends in a blaze of glory, though its opening bars rather lack affection.

Summing up, I feel that it would be unfair to call on comparisons when I have yet to hear the rest of the cycle. That way the pros and cons become meaningful; but what I can say, given the evidence of this particular set, is that in general I prefer Maazel’s London Mahler to its Viennese predecessor.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.