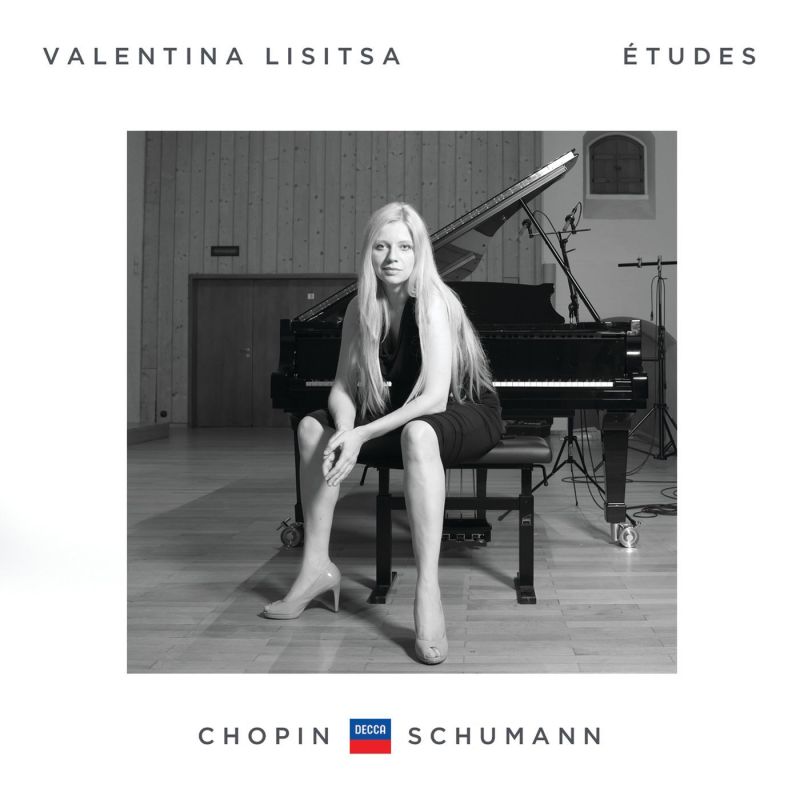

CHOPIN Etudes SCHUMANN Symphonic Etudes

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Robert Schumann, Fryderyk Chopin

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 02/2015

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 85

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 478 7697DH

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Etudes |

Fryderyk Chopin, Composer

Fryderyk Chopin, Composer Valentina Lisitsa, Piano |

| Etudes symphoniques, 'Symphonic Studies' |

Robert Schumann, Composer

Robert Schumann, Composer Valentina Lisitsa, Piano |

| (5) Études symphoniques |

Robert Schumann, Composer

Robert Schumann, Composer Valentina Lisitsa, Piano |

Author: Harriet Smith

Neither of these images is accurate. There’s no doubt that Vinocour has put a lot of research and thought into his readings, and he contributes a fascinating booklet essay. This research reveals itself in all sorts of ways, such as his fleet tempi for Op 10 No 8 and Op 25 No 4 or the rethinking of the so-called ‘Butterfly’, Op 25 No 9, which, as he points out, changes its character entirely when Chopin’s forte and fortissimo markings are observed. But where Vinocour falls down is in matters of technique. The right hand in Op 10 No 2, for instance, just isn’t as even as it needs to be; and too often there’s a sense that he’s right on the edge of his technique – in Op 10 No 8, where he sounds breathless and rushed; or in Op 25 No 11, which is a touch stodgy. Compare him to Sokolov here and you find so much more colour in the Lento opening, which precedes a scorching Allegro con brio.

There’s no such concern with Lisitsa, who has technique in abundance and whose affinity for Chopin is well known. However, she is concerned less with virtuosity and more with revealing the music’s contrapuntal intricacies, which she conveys very strikingly in études such as Op 10 No 7. The opening of the same set is also alluring in its colour and dynamic range, while Op 25 No 1 shimmers evocatively. At times she gets a little carried away, perhaps – her left hand in Op 10 No 4 is arguably overemphatic, while No 5 has none of the glistening airiness of Freire, Perahia or the youthful Pollini. But in the final number of the set she is wonderfully nuanced and reveals plenty of soul.

I have more reservations about her Schumann. For a start, Lisitsa seems to view it less as a coherent piece and more as a set of freestanding virtuoso études; the pianists listed below all offer more of a sense of a unified whole. As with the Chopin, Schumann’s technical demands hold no fear for her (she’s spectacular in numbers such as the Presto possibile of Etude No 9, though even here the insouciant ending is better conveyed by Romanovsky and Cortot). She also tends to be overly generous in her rubato, for instance in the theme itself and in the second and fourth posthumous variations. She takes the finale at a good lick, however, though I was left with the uneasy impression that she sees this as a showpiece, which it certainly isn’t. But her Chopin Etudes are well worth a listen.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.