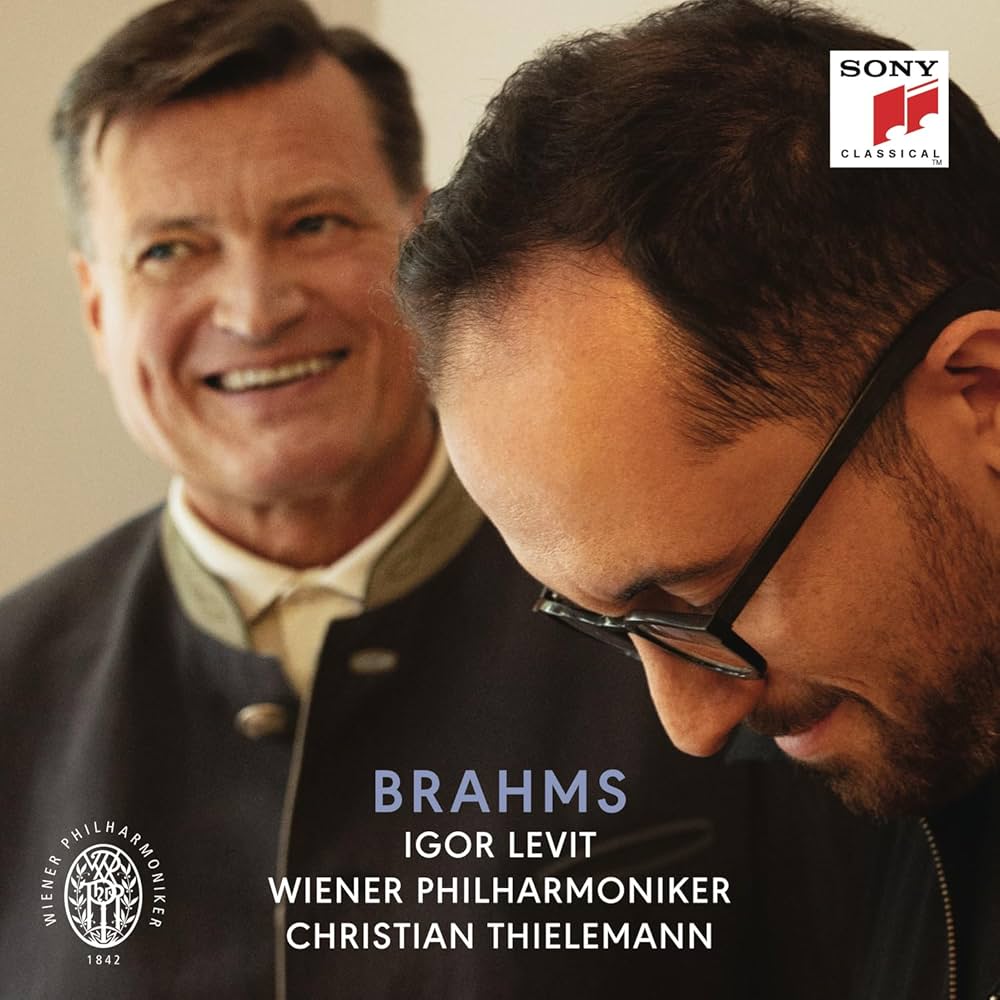

BRAHMS Piano Concertos (Igor Levit)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Sony Classical

Magazine Review Date: 11/2024

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 174

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 19658 89765-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Christian Thielemann, Conductor Igor Levit, Piano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Christian Thielemann, Conductor Igor Levit, Piano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra |

| (7) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Igor Levit, Piano |

| (3) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Igor Levit, Piano |

| (6) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Igor Levit, Piano |

| (4) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Igor Levit, Piano |

| (16) Waltzes, Movement: No. 15 in A flat |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Christian Thielemann, Piano Igor Levit, Piano |

Author: Peter J Rabinowitz

Igor Levit has a well-deserved reputation as one of the most intellectual of pianists – a ‘thinking virtuoso’ (David Fanning, 11/15) notable for his ‘engagement with the smallest detail’ (Harriet Smith, A/19). It’s therefore surprising to read the notes for this new release – a conversation between Levit and Christian Thielemann that makes the two of them sound like intuitive and improvisatory Romantics. Indeed, they tell us, they have such a ‘similar way of thinking’ that they can forego any discussion of particular details and rely instead on unarticulated ‘natural understanding’ and ‘unconditional trust’.

Fear not. Levit hasn’t abandoned his attention to detail. In the concertos, he serves up typically scrupulous performances, with clear textures, surely weighted voicing, precise gestures (trills are superb), finely honed rhythms (try the dotted figures that launch the finale of the Second) and a gorgeous sound, especially in the quieter passages (such as the leggiero passage later in the movement, beginning at bar 105). Throughout, he encourages you to notice nooks and crannies you never have before – but he brings them out subtly, without exaggeration.

Levit hasn’t given up his Apollonian stance, either. True, no one listening to the waves of sound in the first movement of the First Concerto would call the playing reticent. But you wouldn’t call it Dionysian in the manner of Horowitz and Toscanini (APR, 2/01) either. More generally, Levit’s performances are moderate in tempo, often contemplative in spirit. Indeed, many listeners may wish for a little more passion and less control. Thielemann doesn’t help matters here. Take the very opening of the First. Levit describes it as ‘a shock both brutal and cruel’, which is what we get, say, with Serkin and Szell (Philips, 7/55). Here, instead of a shock, we get a dull thud. That serves as a foretaste of the accompaniment in both works: Thielemann and his orchestra provide an impeccable backdrop, but it tends to soak up the music’s emotion.

Turning to the solo works: as in the concertos, there are jolts of vehemence, most notably his biting charge through the Capriccio Op 116 No 7. Affection, too, comes through in a series of sumptuously heart-melting moments: the Intermezzo Op 116 No 4, played at a tempo one might think was unsustainable, evokes a wistful dreamscape of unspeakable beauty; his Intermezzo Op 119 No 2 impresses with its paradoxically refined breathlessness. And throughout the recital, he reveals both flexibility of tempo and sensitivity to timbral nuance. The impressionistic shimmer of the Intermezzo Op 117 No 3 or the exquisite dynamic shading of the Intermezzo Op 119 No 1 would be enough to convince you that this is a pianist out of the ordinary.

Still, in these late pieces, too, Levit remains deeply grounded in the composure for which he is celebrated. For the most part, he’s aloof, even distant, offering nostalgia without sentimentality (listen to the superbly judged sighs that open the Intermezzo Op 116 No 2), poignancy without sharp pain, reflection rather than improvisatory zeal.

Levit came in second in the 2005 Arthur Rubinstein Competition. And in many ways, the outgoing Rubinstein, especially in his 1941 recordings of some of this repertoire, serves as an ideal point of comparison, for his rich colours, clear melodic profiles and bold contrasts bring into relief just how much the more introverted Levit depends on hints and suggestions.

Overall, I find the solo works more engaging than the concertos – and their sound is clearer as well. But it’s hard to imagine any admirer of Brahms who won’t find the concertos worth hearing, too.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.