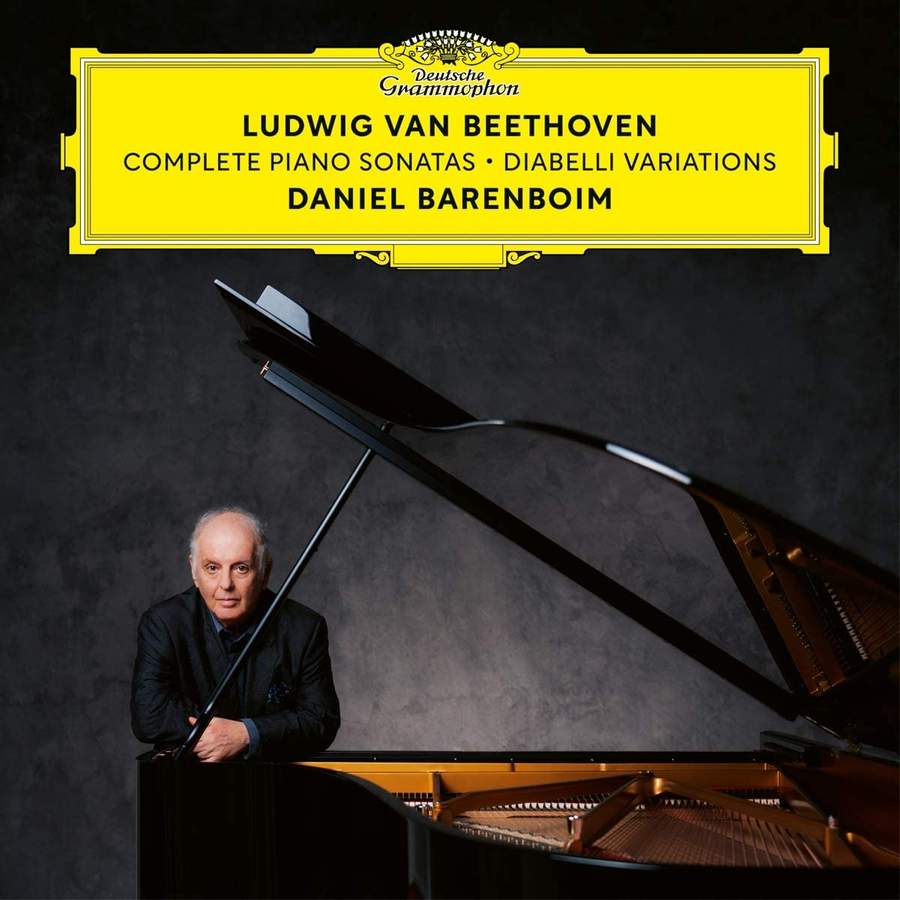

BEETHOVEN Complete Piano Sonatas. Diabelli Variations (Daniel Barenboim)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Magazine Review Date: 12/2020

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 889

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 483 9320

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Complete Piano Sonatas |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Daniel Barenboim, Piano |

| (33) Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli, 'Diabelli Variations' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Daniel Barenboim, Piano |

Author: Harriet Smith

Most of us seem to have spent much of lockdown earlier this year failing to get anywhere with optimistic to-do lists. But Daniel Barenboim isn’t, of course, most people, so it should come as no surprise that the 77-year-old spent it recording his fifth cycle of the Beethoven sonatas in the Pierre Boulez Saal in Berlin. And throwing in the Diabellis for good measure. Intriguingly, this set also includes two discs of sonata recordings made for Westminster in March 1958. But more on that anon.

How to sum up such an undertaking? Well, it’s certainly a mixed bag. Barenboimites will need no encouragement to add it to their collections alongside his earlier surveys. But for the rest of us, frankly, there are caveats. These readings are, as you’d expect, big on personality and long on experience: Barenboim’s love and respect for Beethoven is apparent in every bar. But does that make up for the physical frailty that inevitably dogs some of the more demanding writing?

It’s striking how consistent Barenboim’s approach has been over the decades, tending towards the monumental in slow movements, contrasting this with tremendous energy in quicker movements. Take the Third Sonata, Op 2 No 3, for instance. The second movement is pretty drawn out, closer to a largo than an adagio, but these days the technical difficulties posed by the Scherzo – here more strenuous than playful – and the infamous thirds-and-sixths-infused finale prove a distraction. I’m afraid that issue runs through the entire set and the movements that come off best tend to be the ones at moderate tempos. The theme-and-variation opening of Op 26, for instance, where Barenboim revels in inventive characterisation; he’s also effective in the funeral march of the same sonata, which doesn’t fall into the trap of being too slow. The Tempo d’un menuetto of Op 54 works well, with Barenboim bringing a real intimacy to its opening. The Moonlight begins promisingly, too, with a nice sheen to the first movement and an Allegretto which is limpid in effect. But the Presto is afflicted by unsteadiness and unruly accentuation. Fascinatingly, in this sonata and a handful of others, we can compare the Barenboim of today with his 15-year-old self thanks to the inclusion of two bonus discs. Strikingly, the Moonlight’s first movement is slower in 1958; and while the Allegretto is at a similar pace, it has a perkier alertness to the phrasing. The finale is drier and arguably too fast but technically irreproachable.

How to convey the dramatic extremes of Beethoven’s music is a subject that has long fascinated Barenboim, and the Waldstein is a good example – in both early and new accounts the slow-movement ‘Introduzione’ is very drawn out. The teenage Barenboim goes hell for leather in the first movement – faster than the zippy Igor Levit (Sony, A19) – but the latest version is far more portly, tempo-wise. And the finale, once so slick and easy, now sounds like serious hard work. More problematic still is the Hammerklavier: the youthful account is predictably high on chutzpah, though the slow movement is (understandably) not particularly profound. The new account lacks tension from the off, the corners sound as if they have been smoothed off and by the closing pages of the epic fugal finale the effect is shattered rather than shattering.

There are two accounts of Op 111 as well, and again it’s striking how many elements in the mature Barenboim are already there in his much younger self. The slow introduction is maestoso indeed – too much so for my taste (I much prefer the tautness of Steven Osborne’s vision here, the dotted opening possessing an underlying pulse that eludes Barenboim). And there’s an aggression to the accentation in the Allegro con brio which has become more extreme with time. The Arietta theme is slower in the new account and Beethoven’s final leave-taking of the sonata is more drawn out than previously.

The Diabellis were a brave addition and Barenboim sets off at a purposeful pace, accents nicely observed. You have to admire his refusal to take the more manic variations (such as Nos 10, 15, 19, 27 and 28) at too sedate a pace but that can result in the need for emergency rubato. And by the time he reaches the fugue (Var 32), a strenuousness has crept in.

Anne-Sophie Mutter writes a warm essay about Barenboim and Beethoven, while Julia Spinola’s note talks of Barenboim’s latest cycle having ‘exceptional vitality, clarity, subtle differentiation and precision’; to be honest these were not qualities I encountered except very fleetingly. Approach with caution

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.