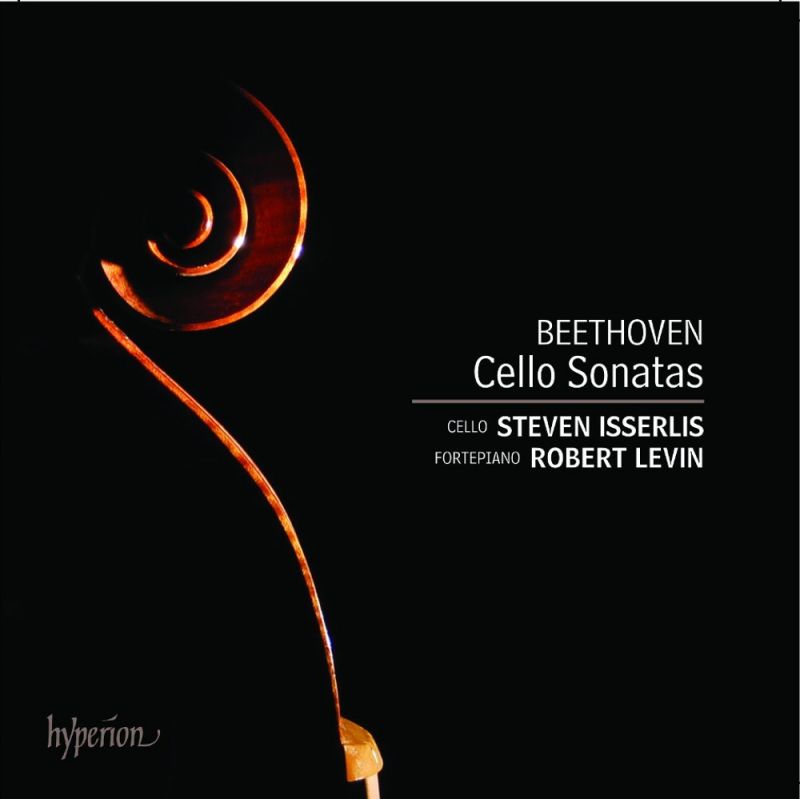

BEETHOVEN Cello Sonatas and Variations

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Chamber

Label: Hyperion

Magazine Review Date: 02/2014

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 159

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: CDA67981/2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Robert Levin, Fortepiano Steven Isserlis, Cello |

| Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 2 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Robert Levin, Fortepiano Steven Isserlis, Cello |

| Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Robert Levin, Fortepiano Steven Isserlis, Cello |

| Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Robert Levin, Fortepiano Steven Isserlis, Cello |

| Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 5 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Robert Levin, Fortepiano Steven Isserlis, Cello |

Author: Nalen Anthoni

A cellist who tends towards introversion; a fortepianist who tends the other way. Put them together and something magical happens within the tensions they engender. Beethoven’s directions for the introduction to Op 102 No 1 are explicit – Andante, softly singing, sweetly, tenderly – and Steven Isserlis, playing a gut-strung 1726 Stradivarius, invokes its beauty in hushed, withdrawn tones. Robert Levin, the moderator on Paul McNulty’s copy of a 1805 Walter & Sohn instrument equalising dynamics, matches him in essence and aura. Think of repose in C major for 27 bars until the switch to the main movement; and the sudden shock of a fortissimo chord in A minor is ruder than it would be on a modern piano. No politesse from Levin. What follows is an untrammelled Allegro vivace, two-in-a-bar as marked, tempo changes graphic, every sforzando or accent stabbing the texture, Isserlis unfurling the vehemence also implicit in his lines.

Recover from the onslaught and return to the beginning, to Op 5 No 1. Repose in C major wasn’t a one-off. It manifests itself again, but now in F major and at a slower tempo, Adagio sostenuto. Isserlis has the theme but Levin is no mere accompanist, fastidious in his role as a partner yet one who never overwhelms the cello, even in the chords and roulades during a brief spell of agitation towards the end of this introduction. Rapid pacing isn’t demanded in the ensuing Allegro – now a plain instruction without an oft-added stipulation, and in common time – of mercurial moods ever present; and laid bare by a duo with no inhibitions about extremes in expressive flexibility.

What did Beethoven often add? Try Allegro molto più tosto presto in the first movement of Op 2 No 2. Pretty quick, pretty specific about how quick too; but Isserlis and Levin are also thoughtful in ensuring that the running triplets for the keyboard aren’t reduced to a frantic, unchecked clatter. Yet power and thrust are unassailable, reinforced by lacerating bowing from Isserlis in the development where screws are tightened – in a movement believed to be one of Beethoven’s most notable achievements, no less so for its expectantly prefaced, grandly fantasia-like 44-bar Adagio sostenuto ed espressivo, for Isserlis and Levin an arch, declamatory and lyrical. With something more – a trenchant edge, probably arising from the timbres of the fortepiano, its light action and fast transients.

It can sing too. Try Allegro ma non tanto, the direction for the first movement of Op 69, probably the best-known work in the set. Isserlis leads expansively, the melody marked p dolce, which is matched by Levin whose part is similarly marked, both locking in to a breadth of scale as suggested by the tempo qualification. Not only does breadth equal magnitude, it includes leeway too. We’re back to expressive flexibility; and we stay with individuals who speak as corporate souls. Tenderness to turbulence, the frames of mind or spirit alter and are neither ignored nor glossed over. Instead they are profoundly felt and candidly declared, through dynamics spanned across the grades end to end, tempi stretched and snapped back into a pulse that doesn’t sag or lose grip. Pick this movement if you fancy trying before buying. But be warned: attracted or repelled, Beethoven may well have the last word. He advocated Gehfühlstempo, the tempo of feeling.

Thus it is that kaleidoscopic distinctions are never underestimated. Neither is attention to detail. Repeats are observed, some decorated. Reactions to emotional currents governing the expansion and contraction of phrases are unflinchingly dramatic. The pliant line is always present, introspectively so in the slow movement of Op 102 No 2, Adagio con molto sentimento d’affetto, for Anton Schindler ‘among the richest and most deeply sensitive inspirations of Beethoven’s muse’, its third section (from 6'21") a whispered exchange between the musicians. In contrast is the Scherzo of Op 69 – with a difference, not new to disc but now far more resolutely proffered. The second of two similar notes tied across bar-lines isn’t silent, for, according to Czerny, Beethoven wanted it to resound like a vibrato. Levin varies his choice of pairs, Isserlis does not; and his repetitions are like echoes feverishly urging the music onwards.

Theirs is a shared experience of audacity and spirituality. Small changes in recorded levels plus a few sniffs are insignificant. They don’t detract from the riches born of scant regard for the superficiality of toeing conventional lines or selecting safe options, shared with listeners in even the less mighty works, the variations and Horn Sonata. This is Beethoven fleshed out by Levin and Isserlis – and anodyne he ain’t here.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.