WEINBERG The Passenger; The Idiot

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Mieczyslaw Weinberg

Genre:

Opera

Label: Arthaus Musik

Magazine Review Date: 02/2016

Media Format: Blu-ray

Media Runtime: 161

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 109 080

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| The Passenger |

Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Composer

Angelica Voje, Krzystina, Mezzo soprano Artur Ruciński, Tadeusz, Baritone Elena Kelessidi, Martha, Soprano Liuba Sokolova, Bronka, Mezzo soprano Michelle Breedt, Lisa, Mezzo soprano Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Composer Prague Philharmonic Choir Roberto Saccà, Walter, Tenor Svetlana Doneva, Katja, Soprano Teodor Currentzis, Conductor Vienna Symphony Orchestra |

Composer or Director: Mieczyslaw Weinberg

Genre:

Opera

Label: Pan

Magazine Review Date: 02/2016

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 208

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: PC10328

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

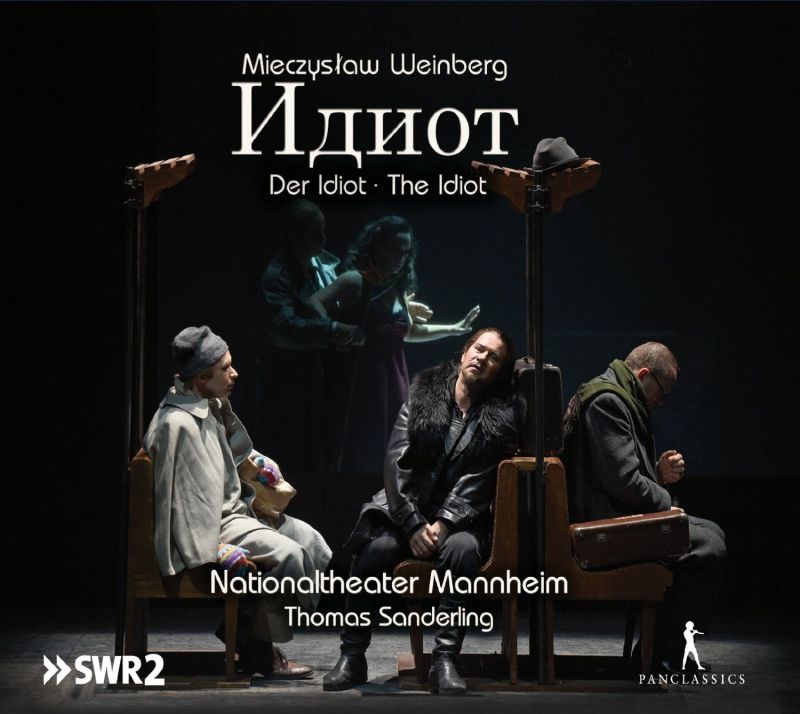

| The Idiot |

Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Composer

Anne-Theresa Møller, Aglaya, Mezzo soprano Bartosz Urbanowicz, Epanchin, Bass-baritone Bryan Boyce, Totsky, Bass Elzbieta Ardam, Epanchina, Contralto (Female alto) Juhan Tralla, Myshkin, Tenor Lars Møller, Lebedjev, Baritone Ludmila Slepneva, Nastassya Filippovna, Soprano Mannheim National Theatre Orchestra Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Composer Steven Scheschareg, Rogozhin, Baritone Thomas Sanderling, Conductor |

Author: David Fanning

The libretto is reworked from Zofia Posmysz’s novella about an ex-Auschwitz guard who re-encounters one of her captives 15 years after the war on a cruise ship (hence the title), and is forced to relive her suppressed memories. Now aged 92 and herself a former inmate, Posmysz is Roman Catholic. The libretto – by musicologist and literary advisor to Shostakovich, Alexander Medvedev – emphasises the international dimension by placing individuals from half a dozen nations among the Auschwitz population. David Pountney’s production takes this idea a stage further by having the text sung in as many different languages. All this has the effect of reducing the Jewish dimension of Auschwitz to virtually zero, and this has been, and will doubtless continue to be, a bone of contention. But it is worth bearing in mind that without Medvedev and Weinberg’s emphasis on universality, endorsed somewhat reluctantly by Posmysz herself, the chances of a production in the Soviet Union at the time of composition (the late 1960s) would also have been close to nil. As it was, plans for staging at the Bolshoi apparently fell foul of intervention ‘from above’, ostensibly on the grounds of the work’s ‘abstract humanism’.

David Pountney and his set designer Johan Engels are faithful to the main concepts of the libretto, setting the post-war scenes on an upper level and sending the camp guard down to the depths for her memories of Auschwitz. Apart from the chorus, who observe and commentate in Greek-tragedy fashion, the staging is realistic and, as a result, as moving as it should be, especially when the screw tightens in the later scenes.

Weinberg might well have made modifications and cuts earlier on had he seen the opera in rehearsal, but even as it stands his pacing is masterful. However, there is one crucial moment where the Bregenz presentation is seriously open to question. This comes in the penultimate scene, where the male inmate, Tadeusz, defies the camp commandant by performing the Bach Chaconne in place of the popular waltz as ordered. Here Medvedev and Weinberg jolt the drama from the realistic to the symbolic by having the music performed by the entire body of orchestral violins in unison and for an unfeasible length of time, before Tadeusz is dragged away and his instrument smashed. The effect, as registered in the first concert performance, given in Moscow in December 2006, is a shattering denunciation of barbarism. But not here, because Pountney has the Chaconne played onstage by a lone soloist, in front of a commandant who soon falls asleep from boredom, thus trivialising one of the most highly charged scenes in all opera.

Having said that, without Pountney’s advocacy The Passenger might never have been staged at all. The Bregenz production had the knife-edge atmosphere of a major rediscovery, and it features strong performances from most of the principals and from the Vienna Symphony Orchestra under Teodor Currentzis (most of whom have a distinct edge over their counterparts at the ENO performances in September 2011). The entire thing is superbly recorded and filmed.

If Weinberg’s first opera is essentially comprehensible without a synopsis, his last certainly needs it: unless, that is, you are familiar with Dostoevsky’s 900-page novel about the ailing and impoverished (though with prospects of a substantial legacy) Prince Myshkin. Kind-hearted to a fault and hence dubbed an ‘Idiot’, Myshkin returns to Russia from a convalescence in Switzerland and starts by visiting distant relatives in St Petersburg. There he meets, among others, the femme fatale Nastassya Filippovna. After many twists and turns, Nastassya is finally dispatched by one of her various unsavoury suitors, Rogozhin. Seemingly able to understand and forgive even this appalling act, Myshkin is seen reconciled with the murderer at the end. Dostoevksy’s own ending was rather different, but this adaptation – again by Medvedev – makes for a profoundly moving conclusion to a compellingly subtle psychological study.

Without the visual aspect – remarkably effective, as anyone present at the Mannheim performances can testify – many will probably find this a long haul, the more so because the score eschews the dramatic immediacy of The Passenger, and because not all the principal voices fall gratefully on the ear (though Juhan Tralle as Myshkin and Ludmila Slepneva as Nastassya are outstanding). But The Idiot has a slow-burn quality, and the longer you stay the course, the more you are likely to realise that Weinberg’s unflashy, flexible yet consistent harmonic language, with its Brittenish command of extended tonality, provides a superb mirror of Myshkin’s tortured soul.

The Mannheim orchestra is understandably stretched by the immensely demanding and in places very exposed scoring, and there are some patches of approximate synchronisation between stage and pit that would have been ironed out under studio conditions. Still, Thomas Sanderling’s unhurried, solicitous conducting pays handsome long-term dividends.

Along with the complete libretto (in four languages) and synopsis, Pan has reproduced the three ‘back stories’ helpfully provided in the original Mannheim Theatre booklet. The recording finds an effective balance between voices and instruments, and moments of stage-shifting noise and the occasional audible prompt are only minimally distracting.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.