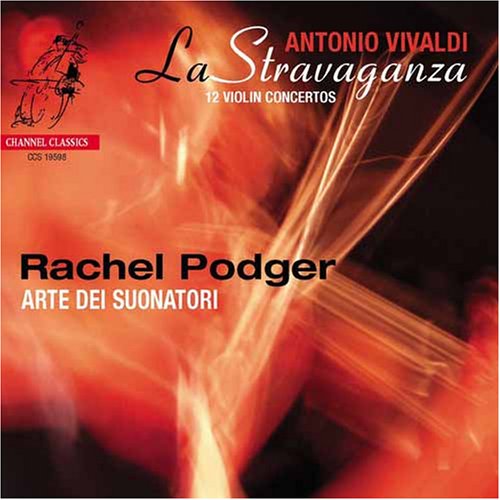

Vivaldi La Stravaganza

Performances that crackle with vitality for those who like Vivaldi at high voltage

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Antonio Vivaldi

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Channel Classics

Magazine Review Date: 5/2003

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 103

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: CCS19598

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (12) Concerti for Violin and Strings, '(La) strava |

Antonio Vivaldi, Composer

Antonio Vivaldi, Composer Arte dei Suonatori Rachel Podger, Violin |

Author: Stanley Sadie

By the standards of the average Vivaldi violin concerto, the La stravaganza set is quite extravagant stuff, full of fantasy and experiment – novel sounds, ingenious textures, exploratory melodic lines, original types of figuration, unorthodox forms. It’s heady music, and listening to its 12 concertos at a sitting, as reviewers are apt to do, isn’t (even with a short lunch interval) a mode of listening I would recommend.

Still less so in performances as high in voltage as the present one. There is a current trend in Baroque performance to get away from the coolness and objectivity which for a long time were supposed (on the whole, mistakenly) to be a part of performing practice of the time, but possibly the pendulum has swung a little wildly the other way. Perhaps here it is intended to reflect Vivaldi’s own notorious freedom of performance. But anyone who has admired earlier recordings with period instruments, such as those by Monica Huggett (L’Oiseau-Lyre, 3/87 – nla) or Simon Standage (Archiv, 1/91 – nla) – by no means cool and objective – may find these a little extravagant (which I suppose is fair enough) and hard-hitting. And they are not helped by the resonant acoustic of the church in Poland used for the recording, in Go´scikowo-Paradyz., which produces a full and bright sound but a boomy bass and less clear a texture than might be ideal. The rather heavy presence of plucked continuo instruments also seems to me a dubious advantage.

That said, however, the performances by Rachel Podger are crackling with vitality and executed with consistent brilliance as well as a kind of relish in virtuosity that catches the showy spirit, the self-conscious extravagance, of this particular set of works. There are plenty of movements here where her sheer digital dexterity is astonishing – I might cite the finale of No 6, with its scurrying figures, the second movement of No 7 (the only four-movement concerto), the finale of No 2 with its repetitive figures and leaping arpeggios, the witty sallies in that of No 3, and the simple rapidity in No 11 – or indeed half a dozen others. But perhaps even more I enjoyed the exquisitely fine detail of some of the slow movements, for example the delicately nuanced line in No 4, the precise articulation in No 1, the rhetorical flourishes in No 9. No 8 in D minor is perhaps the wildest concerto of the lot, with its extraordinary lines in the first movement, the passionate, mysterious outer sections in the second and the powerful and original figuration in the finale: that one has a performance to leave you breathless. Is the first movement too fast? – well, Vivaldi would probably have thought so, but it’s now 300 years later and you are permitted to enjoy it.

Another thing Podger is specially good at is the shaping of those numerous passages of Vivaldian sequences, which can be drearily predictable, but aren’t so here because she knows just how to control the rhythmic tension and time the climax and resolution with logic and force (for that try the first movements of No 4 or No 3, or the second of No 7). There are some movements, such as the first of No 12, that call for, and duly receive, a much lighter touch, and there is similar delicacy and refinement to the playing in the first movement of No 2. In the first movement of No 6, in G minor, she happily catches the aristocratic tone of the invention; this concerto and No 7, with its auxiliary solo violin (which appears in other concertos too) and cello, as well as the odd No 8, seem to me particularly enjoyable. As to my complaint above about hard-hitting performances, try the finale of No 4.

I would certainly recommend this set as a fine example of a modern view of Baroque performance, even if for my own part I am rather happier with performances of the kind typified by the Huggett or the Standage ones.

Still less so in performances as high in voltage as the present one. There is a current trend in Baroque performance to get away from the coolness and objectivity which for a long time were supposed (on the whole, mistakenly) to be a part of performing practice of the time, but possibly the pendulum has swung a little wildly the other way. Perhaps here it is intended to reflect Vivaldi’s own notorious freedom of performance. But anyone who has admired earlier recordings with period instruments, such as those by Monica Huggett (L’Oiseau-Lyre, 3/87 – nla) or Simon Standage (Archiv, 1/91 – nla) – by no means cool and objective – may find these a little extravagant (which I suppose is fair enough) and hard-hitting. And they are not helped by the resonant acoustic of the church in Poland used for the recording, in Go´scikowo-Paradyz., which produces a full and bright sound but a boomy bass and less clear a texture than might be ideal. The rather heavy presence of plucked continuo instruments also seems to me a dubious advantage.

That said, however, the performances by Rachel Podger are crackling with vitality and executed with consistent brilliance as well as a kind of relish in virtuosity that catches the showy spirit, the self-conscious extravagance, of this particular set of works. There are plenty of movements here where her sheer digital dexterity is astonishing – I might cite the finale of No 6, with its scurrying figures, the second movement of No 7 (the only four-movement concerto), the finale of No 2 with its repetitive figures and leaping arpeggios, the witty sallies in that of No 3, and the simple rapidity in No 11 – or indeed half a dozen others. But perhaps even more I enjoyed the exquisitely fine detail of some of the slow movements, for example the delicately nuanced line in No 4, the precise articulation in No 1, the rhetorical flourishes in No 9. No 8 in D minor is perhaps the wildest concerto of the lot, with its extraordinary lines in the first movement, the passionate, mysterious outer sections in the second and the powerful and original figuration in the finale: that one has a performance to leave you breathless. Is the first movement too fast? – well, Vivaldi would probably have thought so, but it’s now 300 years later and you are permitted to enjoy it.

Another thing Podger is specially good at is the shaping of those numerous passages of Vivaldian sequences, which can be drearily predictable, but aren’t so here because she knows just how to control the rhythmic tension and time the climax and resolution with logic and force (for that try the first movements of No 4 or No 3, or the second of No 7). There are some movements, such as the first of No 12, that call for, and duly receive, a much lighter touch, and there is similar delicacy and refinement to the playing in the first movement of No 2. In the first movement of No 6, in G minor, she happily catches the aristocratic tone of the invention; this concerto and No 7, with its auxiliary solo violin (which appears in other concertos too) and cello, as well as the odd No 8, seem to me particularly enjoyable. As to my complaint above about hard-hitting performances, try the finale of No 4.

I would certainly recommend this set as a fine example of a modern view of Baroque performance, even if for my own part I am rather happier with performances of the kind typified by the Huggett or the Standage ones.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.