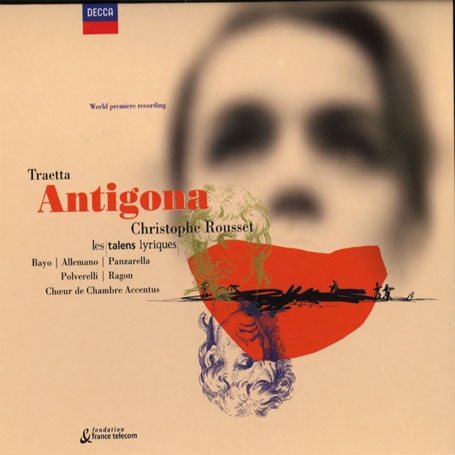

Traetta Antigona

Decca’s recording brings Antigona vividly to life, and should put it – and Traetta – back on the modern musical map

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Tommaso (Michele Francesco Saverio) Traetta

Genre:

Opera

Label: L'Oiseau-Lyre

Magazine Review Date: 3/2001

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 160

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 460 204-2OHO2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Antigona |

Tommaso (Michele Francesco Saverio) Traetta, Composer

(Les) Talens Lyriques Accentus Chamber Choir Anna Maria Panzarella, Ismene, Mezzo soprano Carlo Allemano, Creonte, Tenor Christophe Rousset, Conductor Gilles Ragon, Adrasto, Tenor Laura Polverelli, Emone, Soprano María Bayo, Antigona, Soprano Tommaso (Michele Francesco Saverio) Traetta, Composer |

Author: hcanning

In November 1772, as the 16-year-old Mozart was preparing to astonish the Milanese with his third operatic work for the Teatro Regio Ducal, his older contemporary, Tommaso Traetta (1727–79) from the Puglia region of Italy, was presenting the premiere of his second opera for the court of Catherine the Great in St Petersburg. Today, the former’s Lucio Silla is probably better known than the latter’s Antigona. But which is the finer work? On the basis of this outstanding new recorded version, I would say that Traetta’s tragedia per musica in three acts far outclasses Mozart’s opera seria for its consistent musical inspiration and sheer theatrical know-how. If Traetta’s music were at all familiar to opera-lovers today, that would not be so surprising because this contemporary and disciple of Gluck was, by 1772, an experienced composer for the theatre, already in the prime of a life that was to end, prematurely, only seven years later. His career had taken him from the conservatory in Naples to that city’s famous San Carlo, where his first commission in 1751 was Il Farnace. From there he travelled throughout Europe.

His librettist for Antigona was the celebrated Marco Coltellini, who adapted Goldoni’s La finta semplice for the 10-year-old Mozart in 1766, wrote the original text for Haydn’sL’infedelta delusa (1773) and had collaborated with Traetta on one of his greatest successes, an Ifigenia in Tauride (1763) written for the court of Empress Maria Theresia in the wake of Gluck’s mould-breaking ‘reform’ opera, Orfeo ed Euridice (1762). It was around this time – during his period as court composer in Parma – that Traetta had encountered the tragedies-lyriques of Rameau and written his own operas on similar subjects: Ippolito ed Aricia (1759) and I Tintaridi (Castor and Pollux, 1760) enriched the standard aria-recitative sequences of traditional Italian opera seria with French-style choruses.

Certainly, one can hear the French influence in Traetta’s score for Antigona, which opens with a striking and solemn choral scene including dancing and pantomime; the action depicts the fatal combat of Antigona’s brothers, Eteocles and Polynices. The unwitting listener finds himself plunged into the tragic world of Gluck or the Mozart of Idomeneo (1781) – a work manifestly influenced by Traetta’s and Gluck’s francophile style.

In her illuminating booklet essay, Giovanna Ferrara dubs Antigona ‘an outstanding example of a “reformed” tragedia per musica’, occupying ‘a position half-way between the long-established theatrical taste which saw its own ideals reflected in the spirit of Greek tragedy and the desire for an innovative language free at last from tedious long-windedness, dull moralism and mechanical convention’. In these respects Antigona is very much a transitional work, adapting and developing the opera seria tradition of the da capo aria and bringing dramatic variety to the genre through the extensive use of choruses and the larger ensembles of duet, trio and quartet (these are rare even in a masterpiece such as Mozart’s Idomeneo).

Where Traetta parts company with the reformed Gluck is in his native Italian veneration of virtuoso singing: he wrote the title-role of Antigona for the outstanding soprano, Caterina Gabrielli, and both she and the tenor Prati, creator of Creonte, must have had considerable technical ability judging by the difficulty of their music as recorded here. These parts suggest bravura singers of a stature commensurate with the creators of Mozart’s Elettra and Idomeneo.

Although Coltellini follows the action of Sophocles’ great tragedy fairly closely – he omits the character of Creon’s wife Eurydice – he inevitably adheres to the tradition of the happy end in which the apparently despotic tyrant, Creon, makes the enlightened decision to spare Antigona after his son has made a Radames-like tryst with the incarcerated heroine in her living tomb. Unusually for this period, though, there is no deus ex machina: Creon is made to see the error of his severity by the humanity and love of his son Hemon’s actions. The Tsarina would have been flattered by this picture of despotic magnanimity.

As I have indicated, Traetta’s music is of a very high quality, if perhaps lacking the spark of genius that distinguishes Idomeneo or Iphigenie en Tauride as two of the 18th century’s greatest operas. He writes beautifully for women’s voices – his duets for Antigona and her sister, Ismene, for Ismene and Emone – a mezzo-soprano castrato part – foreshadow that of Fiordiligi and Dorabella in Cosi fan tutte or Servilia and Annio in La clemenza di Tito. His approach to the aria is often highly innovative: Act 2 closes with a bravura number for the heroine whose ‘coda’ is a duet for Ismene and Emone. One of the most striking passages in the score is the funerary chorus at the beginning of Act 2 in which Antigona illegally cremates the remains of her degraded brother and cries out his name, Polinice – like Orpheus bemoaning Eurydice in the opening chorus of Gluck’s opera.

Decca’s recording certainly deserves to put Antigona – and Traetta – back on the modern musical map: Christophe Rousset’s musical direction of his Talens Lyriques is evangelical in its fervour. The French conductor – with his experience oftragedie-lyrique and Italian opera seria – really knows how to bring a hybrid piece such as this vividly to life. Although the recording is based on concert performances at the Beaune International Festival of Baroque Music (strictly speaking Traetta is high-classical), it has a highly charged theatrical atmosphere thanks to Rousset’s dynamic and expressive conducting. It is possible, I think, to imagine more vocally charismatic singers for the leading roles; listening to Maria Bayo’s fluent, effortless coloratura and sweet but slightly soubrettish timbre in the title-role, I hankered for the richer sound and more tragic demeanour of, say, a Cecilia Bartoli, but we can’t have Bartoli in everything and Bayo’s singing is never less than accomplished. A nobler, darker tone than that possessed by Carlo Vincenzo Allemano might lend greater gravitas to Creon’s part, but the Italian tenor copes extremely well with the demanding fioriture of the part and is especially successful at suggesting the pent-up fury of the Theban tyrant when his orders are flouted by his niece. Anna Maria Panzarella’s warm, slightly husky tone contrasts well with the brightness of Bayo’s in their duets, and the Italian mezzo Laura Polverelli blends well with both voices as Antigona’s betrothed, Emone.

Gilles Ragon completes the cast of soloists stylishly in the role of Creon’s confidant, Adraste. The choral singing is superb in an issue which ought to do for the composer of Antigona what Rene Jacobs’ pioneering recording of Croesus (Harmonia Mundi, 12/00) has done for Reinhard Keiser. More Traetta, please.'

His librettist for Antigona was the celebrated Marco Coltellini, who adapted Goldoni’s La finta semplice for the 10-year-old Mozart in 1766, wrote the original text for Haydn’s

Certainly, one can hear the French influence in Traetta’s score for Antigona, which opens with a striking and solemn choral scene including dancing and pantomime; the action depicts the fatal combat of Antigona’s brothers, Eteocles and Polynices. The unwitting listener finds himself plunged into the tragic world of Gluck or the Mozart of Idomeneo (1781) – a work manifestly influenced by Traetta’s and Gluck’s francophile style.

In her illuminating booklet essay, Giovanna Ferrara dubs Antigona ‘an outstanding example of a “reformed” tragedia per musica’, occupying ‘a position half-way between the long-established theatrical taste which saw its own ideals reflected in the spirit of Greek tragedy and the desire for an innovative language free at last from tedious long-windedness, dull moralism and mechanical convention’. In these respects Antigona is very much a transitional work, adapting and developing the opera seria tradition of the da capo aria and bringing dramatic variety to the genre through the extensive use of choruses and the larger ensembles of duet, trio and quartet (these are rare even in a masterpiece such as Mozart’s Idomeneo).

Where Traetta parts company with the reformed Gluck is in his native Italian veneration of virtuoso singing: he wrote the title-role of Antigona for the outstanding soprano, Caterina Gabrielli, and both she and the tenor Prati, creator of Creonte, must have had considerable technical ability judging by the difficulty of their music as recorded here. These parts suggest bravura singers of a stature commensurate with the creators of Mozart’s Elettra and Idomeneo.

Although Coltellini follows the action of Sophocles’ great tragedy fairly closely – he omits the character of Creon’s wife Eurydice – he inevitably adheres to the tradition of the happy end in which the apparently despotic tyrant, Creon, makes the enlightened decision to spare Antigona after his son has made a Radames-like tryst with the incarcerated heroine in her living tomb. Unusually for this period, though, there is no deus ex machina: Creon is made to see the error of his severity by the humanity and love of his son Hemon’s actions. The Tsarina would have been flattered by this picture of despotic magnanimity.

As I have indicated, Traetta’s music is of a very high quality, if perhaps lacking the spark of genius that distinguishes Idomeneo or Iphigenie en Tauride as two of the 18th century’s greatest operas. He writes beautifully for women’s voices – his duets for Antigona and her sister, Ismene, for Ismene and Emone – a mezzo-soprano castrato part – foreshadow that of Fiordiligi and Dorabella in Cosi fan tutte or Servilia and Annio in La clemenza di Tito. His approach to the aria is often highly innovative: Act 2 closes with a bravura number for the heroine whose ‘coda’ is a duet for Ismene and Emone. One of the most striking passages in the score is the funerary chorus at the beginning of Act 2 in which Antigona illegally cremates the remains of her degraded brother and cries out his name, Polinice – like Orpheus bemoaning Eurydice in the opening chorus of Gluck’s opera.

Decca’s recording certainly deserves to put Antigona – and Traetta – back on the modern musical map: Christophe Rousset’s musical direction of his Talens Lyriques is evangelical in its fervour. The French conductor – with his experience of

Gilles Ragon completes the cast of soloists stylishly in the role of Creon’s confidant, Adraste. The choral singing is superb in an issue which ought to do for the composer of Antigona what Rene Jacobs’ pioneering recording of Croesus (Harmonia Mundi, 12/00) has done for Reinhard Keiser. More Traetta, please.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.