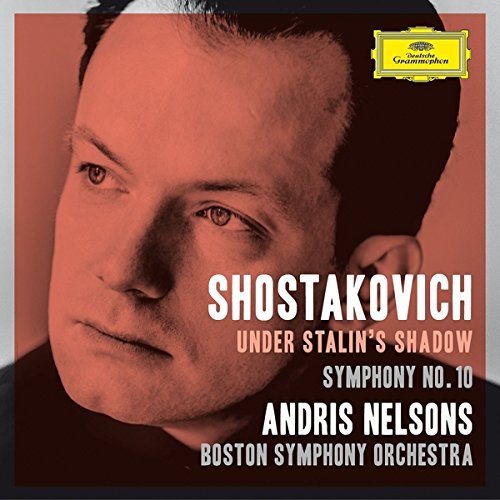

SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No 10

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Dmitri Shostakovich

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Magazine Review Date: 08/2015

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 65

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 479 5059GH

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 10 |

Dmitri Shostakovich, Composer

Andris Nelsons, Conductor Boston Symphony Orchestra Dmitri Shostakovich, Composer |

| Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk district, Movement: Passacaglia |

Dmitri Shostakovich, Composer

Andris Nelsons, Conductor Boston Symphony Orchestra Dmitri Shostakovich, Composer |

Author: Edward Seckerson

So shock-and-awe arrives with a vengeance in the screaming organ-like chords which portend Katerina Izmailova’s destiny – the State bearing down on this liberated woman for the crimes to which she has been driven. It is the musical embodiment of oppression, this extraordinary interlude, and the irony is that Stalin should not recognise it as such but rather find offence in its crushing dissonance. And, my goodness, Nelsons lays down the monster climax with almost obscene relish, howls of derision from the woodwind choir and the Boston trumpets recalling a thrilling stridency from days of yore when the principal from the Münch and Leinsdorf eras would lend a steely, blade-like gleam to the tutti sound.

It’s a really affecting segue then from the impenetrable darkness of its closing bars into the long string bass-led introduction of the Tenth Symphony. Nelsons’s performance is mighty, marked by a wonderful nose for atmosphere and a way of making space for the succession of desolate wind solos – first clarinet, later bassoons and piccolos.

The inexorability of this beautifully proportioned, arch-like first movement is judged to perfection. There is that forlorn little dance for flute that morphs into a cry of such despair in the huge development climax and later emerges in clarinets striving hope against hope to keep the spirit of optimism alive.

I mentioned the despairing climax of this movement, an upheaval so great and so protracted as to seem insurmountable – but what makes Nelsons so lethally impressive here is the precision with which he addresses every accent, every ferocious sforzando. He is the most rhythmic of conductors and the trumpet topped brass here are possessed of a unanimity that makes them absolutely implacable.

I should add that every thematic motif, every cross-reference and transformation is clearly delineated. Not in any sense forensic, as in sterile, just startlingly clear. And as Nelsons negotiates the aftermath of this crisis with great intakes of breath from his cellos and basses, we come full-circle into the bleak coda, where two piccolos vainly attempt a consoling roundelay.

The whirlwind scherzo ensues – and whether or not this was intended as a thumbnail sketch of Stalin tearing through the fabric of the symphony is immaterial: something destructive this way comes, and at great speed. Well, more the illusion of speed (emphatic and imperative) because again it’s the rhythmic precision, the snap of the syncopations and absolute security in the playing of them that takes the breath away. When the trombones make their invasive presence felt midway through the movement there is more than a hint of Red Army bullyboy tactics in the attitude they convey and, by contrast, Nelsons makes much of that eerie motoric passage in the strings which follows, as if quietly generating more energy for the closing bars.

So much for the ‘before’. Emerging from the dust of the scherzo comes the ‘after’ – the composer reasserting his identity in the coded musical form of his own monogram, DSCH. It’s there almost before you know it, offsetting evocative horn solos (beautifully attended by the BSO principal) and reiterating itself through the folk dance at the heart of the Allegretto. What a mysterious movement this is (closer to a Mahlerian Nachtmusik than anything else in Shostakovich) and how subtly Nelsons explores its shadowy subtext.

I have mentioned the beauty and personality of the wind-playing throughout this performance, and the plaintive oboe solo which first scents a new dawn at the start of the finale is especially poignant. Be in no doubt that this is one of the finest performances that I have ever heard of this great piece (it must surely bid fair for ‘best in catalogue’) and to say that it augurs well for Nelsons’s future with the Boston Symphony is an understatement and then some. This was a shrewd appointment.

Symphony Hall, Boston (modelled after Vienna and Amsterdam) sounds wonderful, too, the thunderous restatement of the DSCH motif at the heart of the finale packing a huge punch and preparing us for the fireworks of the coda, where defiant timpani have almost the last word with it. Almost, but not quite. Stalin may have been dead but his pernicious legacy was very much alive.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.