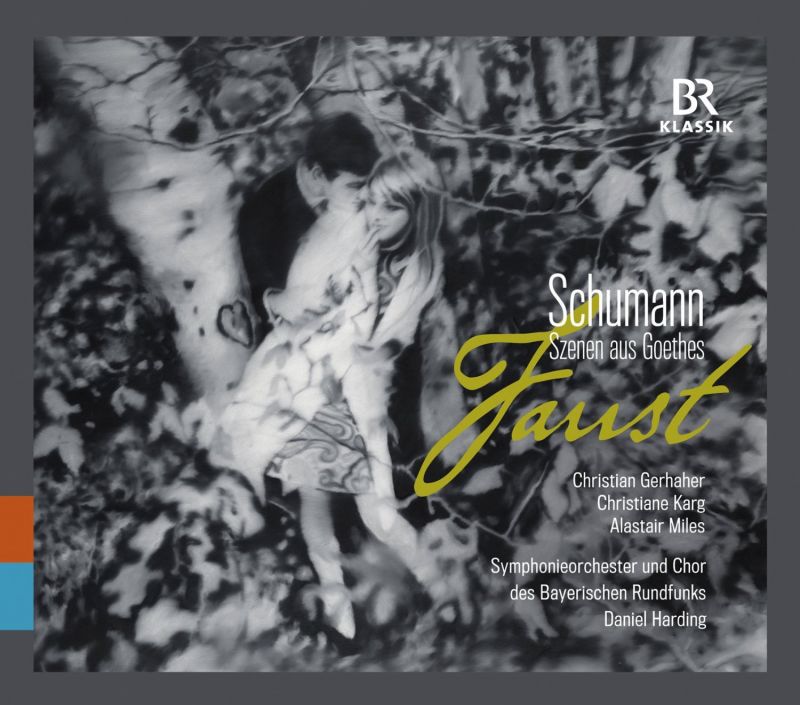

SCHUMANN Scenes from Goethe's Faust

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Robert Schumann

Genre:

Vocal

Label: BR Klassik

Magazine Review Date: 12/2014

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 115

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 900122

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Szenen aus Goethes Faust |

Robert Schumann, Composer

Alastair Miles, Bass Andrew Staples, Tenor Bernarda Fink, Mezzo soprano Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks Christian Gerhaher, Baritone Christiane Karg, Soprano Daniel Harding, Conductor Kurt Rydl, Bass Mari Eriksmoen, Soprano Robert Schumann, Composer Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Tareq Nazmi, Bass |

Author: Peter Quantrill

This experience all tells to the good. Past the blocky formalities of the Overture (composed last, in 1853), it’s quickly apparent how text-driven and song-soaked is this marvellous live recording. When people criticised Schumann’s orchestral music, they were criticising him for not being Beethoven or Brahms. Whether or not the Bavarian radio orchestra is at full strength – and the cathedral scene of the first part lacks nothing in impact, led by Alastair Miles at his most stentorian as the Evil Spirit – they play with the easy mobility of a chamber group, reduced but not minimal vibrato and the dynamic restraint needed to register Schumann’s particular orchestral tinta with its emphasis on wind and brass at the extremes of their registers: the high piccolos and low trombones used not to represent superficial heaven/hell polarities but as a scenic backdrop (after Mendelssohn’s example in The Hebrides, and prefiguring Gurrelieder in this regard), lending perspective to Faust, the baritone in the centre of the picture. The German oratorio tradition seems less relevant to both piece and recording than the late canvases of Turner such as The Great Western Railway, in which man stands at the edge of abstraction, as if setting Goethe’s words for Faust’s death. In Harding’s chorale-like chord-placing of the sublime orchestral epilogue to Part 2, we may hear both the Bach evoked by Schumann as he substitutes Goethe’s ‘Es ist vorbei’ for the biblical echoes of ‘Es ist vollbracht’, and, in its aching suspensions, Mahler the songsmith. Gerhaher contends that this substitution shows how Faust has been canonised by Schumann, and calls up cross-motifs in the Chorus Mysticus as supporting evidence, but I hear more musical than religious motivation in the opus summum of a composer whose faith was anything but steadfast or conventional.

As Faust, Christian Gerhaher is more intimate with us and with Goethe than on Harnoncourt’s recording, even (this may be heresy for some) besting his teacher Fischer-Dieskau, who had such feeling for and experience of this role. Besides the philosopher-king side of the character, with which Gerhaher shows himself intellectually at home in a fascinating interview reprinted in the booklet, he has at his disposal the charm of the teasing lover as he banters in the garden with Christiane Karg’s Gretchen. His ‘Lebt wohl’ at the end of this scene is a small masterpiece of regret, ardour, bravado and hope, as rich in nuance as a fine Marschallin’s ‘Ja ja’. Backed by some pointful conducting and beautifully dovetailed playing of Gretchen’s stock confession scene, Karg brings to it a softer, more yielding but less personal vocal profile than the piercing tremulousness of Elizabeth Harwood for Britten.

Harding’s tripping pulse and tenderly drawn legato is ideal for the twilit prelude to Part 2; and while he doesn’t quite conjure the Mendelssohnian magic of Abbado, he has Andrew Staples (the tenor for his Peri performances), who as Ariel sustains an elevated line and mood better than the slightly stiff approach of Werner Güra for Harnoncourt and the curiously miscast Wagnerian tenor Endrik Wottrich for Abbado. The smaller roles are all well taken but in parts such as the midnight scherzo it is the orchestra who say even more than the singers, with many subtle variations of string vibrato and wind colour. At the centre of Part 2 is Faust’s wondering hymn to nature’s glories, and this finds Gerhaher at his finest, using consonants to spring across phrases like stones in a brook.

Considering the Scenes have no narrative thread to speak of, it might even be thought useful to listen to them as Schumann composed them, backwards, for the third part, begun in 1844, breathes an air of sustained inspiration scarcely less rarefied than the second part of Peri from the previous year. The narrative flow imparted by Harding (and Schumann) is even more evident and admirable, however, if the solemn, Rhenish prelude to Part 3 is heard in the light of the end of Part 2. Here the chorus breaks free from call-and-response conventions, happily given due prominence in the warm Herkulessaal acoustic and well balanced across the parts so we can relish Schumann’s hovering, sixth-tinted harmonies. The boys from Augsburg are, indeed, as ‘blessed’ as Goethe commands, bright, fragile and perfectly tuned.

When the Chorus Mysticus is reached, Schumann’s apotheosis – kept flowing and light-filled by Harding – does make Mahler’s setting in the Eighth feel as overblown as his detractors would have you believe. Here are no suns and planets revolving but a human soul finding rest. Talking of Schumann, Gerhaher remarks that ‘this is a version of Faust one can really indulge in’. Of this performance, I can only echo his sentiments.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.