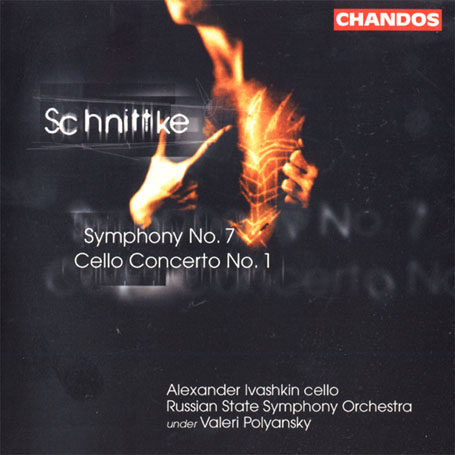

Schnittke Symphony 7 & Cello Concerto 1

Severe music, expertly performed, that will appeal to admirers of Schnittke, but others may be dissuaded by its relentless morbidity

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Alfred Schnittke

Label: Chaconne

Magazine Review Date: 9/2000

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 64

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: CHAN9852

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 7 |

Alfred Schnittke, Composer

Alfred Schnittke, Composer Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valéry Polyansky, Conductor |

| Concerto for Cello and Orchestra No. 1 |

Alfred Schnittke, Composer

Alexander Ivashkin, Cello Alfred Schnittke, Composer Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valéry Polyansky, Conductor |

Author: Michael Oliver

After his catastrophic stroke in the summer of 1985 Alfred Schnittke’s music changed radically, becoming violently expressionistic and often brutally dissonant. The First Cello Concerto was written immediately after that close approach to death, the Seventh Symphony nine years later, but although the concerto is the more savage of the two (and is, besides, almost twice as long), the symphony is even more bleakly pessimistic. They make a very grim coupling indeed.

From its gloomy opening (a sad violin solo gradually joined by other strings in harsh counterpoint), the Symphony soon proceeds, especially in its long last movement, to a series of isolated gestures. Some are marginally less bleak (a brief moment of tranquillity in the horns), but all die or falter in a depiction of frustrated despair. There is a brief gleam of grace from the woodwind, but then all the lowest instruments of the orchestra (tuba, contrabassoon, double-bass, bass drum) join in a banal funereal waltz. The Concerto begins rather similarly: a mournful cello solo over a drone. But this is quickly snuffed out by shrieking dissonance and soon a pattern is built up of repetitious conflict between tearfulness and ferocity. In the second movement the cello grieves at greater if histrionic length; the Scherzo has grim energy, alongside a Shostakovich-and-water main idea and further roars of pain. There follows a grindingly dissonant quasi-passacaglia (described by Schnittke as a ‘prayer’) which becomes ‘increasingly ecstatic’. It does indeed rise to a huge climax which requires the solo cello to be amplified.

This is the Concerto’s fifth recording (and the Symphony’s second) and I cannot imagine it being played with more commanding virtuosity or more rhetorical intensity; like the symphony it is finely recorded. Any reaction to a contemplation of death is bound to be subjective, but to me both these works seem not only intensely depressing but hysterically over-stated.'

From its gloomy opening (a sad violin solo gradually joined by other strings in harsh counterpoint), the Symphony soon proceeds, especially in its long last movement, to a series of isolated gestures. Some are marginally less bleak (a brief moment of tranquillity in the horns), but all die or falter in a depiction of frustrated despair. There is a brief gleam of grace from the woodwind, but then all the lowest instruments of the orchestra (tuba, contrabassoon, double-bass, bass drum) join in a banal funereal waltz. The Concerto begins rather similarly: a mournful cello solo over a drone. But this is quickly snuffed out by shrieking dissonance and soon a pattern is built up of repetitious conflict between tearfulness and ferocity. In the second movement the cello grieves at greater if histrionic length; the Scherzo has grim energy, alongside a Shostakovich-and-water main idea and further roars of pain. There follows a grindingly dissonant quasi-passacaglia (described by Schnittke as a ‘prayer’) which becomes ‘increasingly ecstatic’. It does indeed rise to a huge climax which requires the solo cello to be amplified.

This is the Concerto’s fifth recording (and the Symphony’s second) and I cannot imagine it being played with more commanding virtuosity or more rhetorical intensity; like the symphony it is finely recorded. Any reaction to a contemplation of death is bound to be subjective, but to me both these works seem not only intensely depressing but hysterically over-stated.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.