ROSSINI Il barbiere di Siviglia (Rhorer)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Gioachino Rossini

Genre:

Opera

Label: Naxos

Magazine Review Date: 12/2019

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 159

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 2 110592

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (Il) Barbiere di Siviglia, '(The) Barber of Seville' |

Gioachino Rossini, Composer

Annunziata Vestri, Berta, Mezzo soprano Catherine Trottmann, Rosina, Soprano Florian Sempey, Figaro, Baritone Gioachino Rossini, Composer Guillaume Andrieux, Fiorello, Baritone Jérémie Rhorer, Conductor Le Cercle de l’Harmonie Michele Angelini, Almaviva, Tenor Peter Kálmán, Doctor Bartolo, Bass-baritone Robert Gleadow, Don Basilio, Bass-baritone Stéphane Facco, Ambrogio, Bass Unikanti |

Author: Richard Osborne

It was in the 1920s that musicians began recognising the neoclassical nature of Rossini’s comic art. First, there was his use of form as the seedbed of wit, a skill mainly learnt from Haydn’s instrumental works. Second, there was his debt to commedia dell’arte with its use of caricature and mime, and its own bespoke choreography. The wonder of Il barbiere, and the reason for its survival as an operatic classic, lies in the skill with which Rossini melded these two disciplines.

Not that I have ever seen this fully realised – until now, and this pitch-perfect telecast of Pelly’s own pitch-perfect staging. The experience calls to mind Furtwängler’s memory of a performance of Die Meistersinger in Bayreuth in 1912 conducted by Hans Richter: ‘There was no sense of our being in an opera house. The impression was of a conversation piece, with all the points made as they would be made in a spoken play. One was not conscious of the music, yet the performance took place in so musical an atmosphere that the effect was utterly overwhelming.’ It’s the same here. One hangs on to the drama’s every word, oblivious of the form the ‘backing’ music is taking, be it aria, duet, secco recitative or madcap finale.

‘The whole joyous point of Il barbiere’, Rodney Milnes once remarked, ‘is that all the characters are opportunist monsters, which is why, gazing into the proscenium mirror, we all love it so much.’ The monster-in-chief, Pelly rightly divines, is the tyrannical (the libretto’s word) Dr Bartolo, played in comic caricature with pinpoint precision by the great Hungarian singer-actor Peter Kálmán.

Outwitted by Figaro, and hypnotised by Robert Gleadow’s imperturbably seedy Basilio (his Calumny aria brilliantly staged by Pelly), the good doctor gets his ultimate comeuppance from Count Almaviva in a bazooka of a performance by Michele Angelini of ‘Cessa di più resistere’, the big end-of-opera aria that’s usually cut but, as Pelly proves, is crucial to the drama’s resolution.

Given that Pelly works with players of quality, while ensuring that the production’s every detail is of a piece with itself, it’s not surprising that this is a wonderfully well-acted Il barbiere, whether played straight or, in a couple of musical divertissements, vaudeville-style with follow-spots.

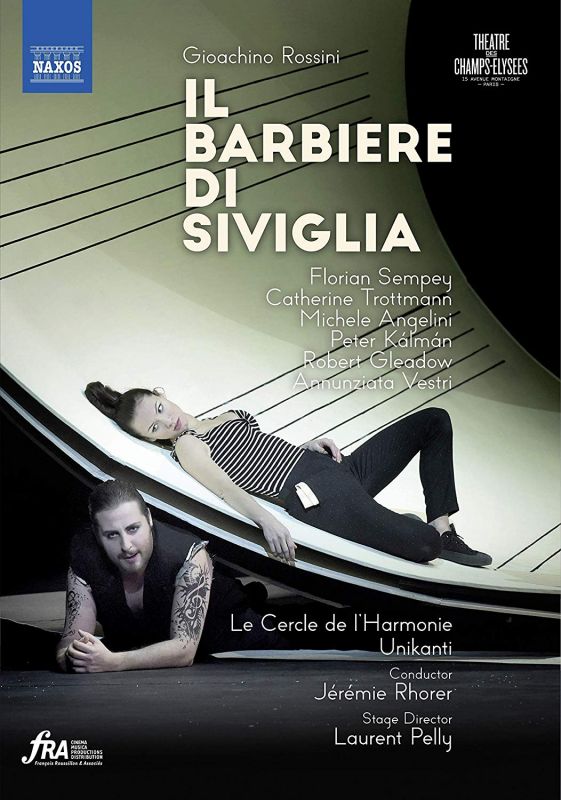

Florian Sempey’s Figaro is a tattooed bruiser in commando boots and a cut-away tailcoat who, swearing by the ‘eternal gods’, twice makes his entry from above like some deus ex machina. Since Dr Bartolo is manifestly the cause of his own downfall, Figaro can happily revert to type as the peripatetic intriguer. Meanwhile, Catherine Trottmann’s diminutive Rosina, every inch the alluring teenage troublemaker with her tight black jeans and karate-chop mobility, fights like a ferret in a sack to escape this strange world of deranged old men. Like everyone else, she sings with aplomb from just about every conceivable pose and position.

Music itself is often mentioned in Beaumarchais’s Le barbier de Séville, a point Rossini seized on with avidity. Hence the use of a musical trope in Pelly’s elegantly designed (mainly black-and-white) costumes and sets, as the action is played within and around giant sheets of ivory-coloured music paper. The grilles which guard Bartolo’s gated domain resemble staves of music. Amid the mayhem of the Act 1 finale – superbly staged by Pelly – it is folding music stands, not muskets, that are the local militia’s weapon of choice.

Rossini learnt his theatre craft as an improvising cembalist, yet I doubt whether even he could have provided a wittier or more pertinent commentary on the action than that conjured up by the matchless Paolo Zanzu.

The final salute, however, must go to Jérémie Rhorer and the period instrumentalists of his Le Cercle de l’Harmonie. Rhorer looks younger than his 46 years, but premier cru wines are not made overnight and this, by any measure, is premier cru conducting. Verdi praised Rossini’s ‘truth of declamation’ in Il barbiere. That’s the gold standard by which Pelly’s cast operates, yet it takes some doing to follow every twist and turn of conversation, without once allowing us to feel that the Rossini express isn’t running smoothly and to time. My, what skills are on display in every department of this astonishing production!

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.