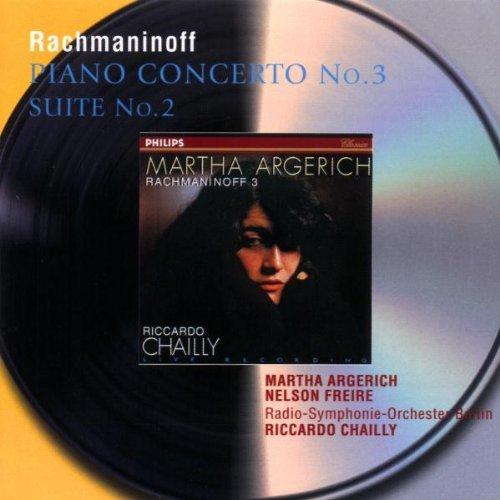

Rachmaninov Piano Concerto 3 & Suite 2

Some genuine gems‚ superbly transferred‚ from Argerich‚ Mullova‚ Richter and Brendel with just one – or two – of questionable merit

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Sergey Rachmaninov

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: 50 Great Recordings

Magazine Review Date: 9/2001

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 62

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 464 732-2PM

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Sergey Rachmaninov, Composer

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Martha Argerich, Piano Riccardo Chailly, Conductor Sergey Rachmaninov, Composer |

| Suite No. 2 |

Sergey Rachmaninov, Composer

Martha Argerich, Piano Nelson Freire, Piano Sergey Rachmaninov, Composer |

Author:

This latest batch from the Philips 50th anniversary list contains remarkably few duds. The 24bit transfers are expertly done and the design concept is consistently applied (if perhaps too obviously derived from rival series). Only the annotations‚ normally a plus point with material from this source‚ betray signs of haste. The booklets cite no recording personnel and I was disappointed by the mix of old and new programme notes‚ signed and unsigned‚ some about the works‚ some about the performances‚ and with untidy shifts of gear between the two in the case of the Argerich and Grumiaux issues.

I dare say there will be some readers who find Martha Argerich’s playing choppy and overinflected‚ but here in 1982 she is at the very top of her form in classic Rachmaninov. I am not sure to what extent her thrilling live account of the Third Piano Concerto is in any real sense a Philips production. What matters is that it has always sounded better than you might expect – if the insistent ‘clang’ of the modern piano is inescapably evident‚ so too is her breathtaking command of tone colour. Not perhaps the obvious choice for this repertoire‚ Riccardo Chailly and his then orchestra are led a merry dance yet manage to stay with her. The recoupling with the Suite is apt rather than generous. Lacking the gravitas of Vladimir Ashkenazy and André Previn on a famous rival recording (London‚ 455 2342LC6)‚ Argerich and Nelson Freire compensate with a vein of poetic fantasy and a propulsive energy that Argerich herself could not quite equal in her subsequent Teldec version (9/92). With Freire on the righthand channel taking the second part‚ the clarity of articulation is a constant delight.

Unlike Argerich‚ Viktoria Mullova has long been a Philips stalwart‚ so it is especially appropriate that the company has chosen to include her début recording‚ made after her dramatic defection to the West in 1983. I had forgotten how good this was. No player of her generation has a more powerful technique‚ and her heroic objectivity and huge dynamic range suits the Sibelius down to the ground. Even if the balance tends to relegate Ozawa’s orchestra to a frankly accompanimental role (rich‚ dark and warm but a little lost in the resonance)‚ Mullova’s own sound is caught superbly well. And what a sound it is! The Tchaikovsky is equally strong and brilliant‚ although the Iron Maiden approach suits the music less well; it may be that Mullova has since become a more adaptable if not more keenly sensitive player.

It’s no surprise to find Sviatoslav Richter’s Liszt included in this top 50. Dating from July 1961‚ these concerto recordings have been highly regarded for 30 years‚ with only the couplings and the transfers changing over time. Indeed such is the status of these performances that BBC Legends has released a tape of the Albert Hall concert that preceded the sessions (4/00). The studio sound is better of course‚ the very bold and forward effect being the result of Mercury sound engineering. Romantic swagger is here tempered by the most delicate poetry‚ with Richter on dazzling form and Kondrashin equally engaged‚ getting much more precise results from the LSO than he seemed able to elicit from Western orchestras later in life. It’s not all plain sailing – on the first piano entry in the Second Piano Concerto‚ piano and orchestra are as painfully out of tune as they always were – and I did wonder about the new choice of makeweight. Richter is a great Beethoven player‚ but need these particular works sound so austere? The shallow sonority of the piano and the high hiss levels certainly don’t help. Whereas the Liszt should be in every collection.

George Szell was a formidably toughminded figure who was often said to ‘relax’ on his European jaunts away from his Cleveland base. Be that as it may‚ the Concertgebouw Orchestra of the mid1960s was not the band it had been and has since become‚ and Szell seems here to be concentrating on getting the splenetic precision he wants at the expense of flexibility and warmth. There are some unexpected interpretative touches in the Beethoven to break up the impression of generalised aggression‚ and the recording has plenty of presence even if the orchestral image will perhaps strike younger listeners as inappropriately bloated. The Sibelius‚ much acclaimed in the past as a classicist’s rebuff to romantic excess‚ I found inappropriately tense – combustible yes but at times merely heartless‚ with some very harddriven tempos in the ‘slow’ movement. For my money‚ Toscanini had a much more natural feeling for the idiom – never mind Beecham‚ Barbirolli and the rest – and yet Trevor Harvey‚ writing in these pages in 1965‚ called it ‘the most inspired performance of Sibelius’s Second I have ever heard’. It may still be among the most disciplined but I can’t say I liked it. The damped down recording conveys little in the way of hall resonance.

Another artist with a substantial reputation who‚ for me‚ doesn’t always ‘deliver’ is Alfred Brendel‚ but he has recorded all the Mozart piano concertos for Philips at least once and in no other music is his playing more bonded to the music’s expressive life – to paraphrase the words of Stephen Plaistow. Moreover‚ Philips here very generously present three outstanding performances from his intégrale with Sir Neville Marriner’s Academy of St Martin in the Fields – K450 and 467‚ set down as recently as May 1981‚ and K488 from June 1971. Brendel keeps things moving in his radically rethought‚ supremely articulate K467‚ while the older (and broader) reading of K488‚ one of the first Mozart concertos he recorded for the label‚ still sounds fresh although the sound is differently focused. Brendel has written most eloquently of his own approach to the composer‚ rejecting ‘the cute Mozart‚ the perfumed Mozart‚ the permanently ecstatic Mozart’‚ even the incessantly poetic Mozart of players stuck ‘in a hothouse in which no fresh air can enter...Let poetry be the spice‚ not the main course.’ There is no better entrée than the present CD.

Blandness looms with the remaining Mozart offerings‚ although‚ unless you want a more incisively projected alternative informed by period practice‚ the vintage Mozart LPs of Arthur Grumiaux stand up well enough. In the concertos‚ the young Colin Davis elicits vigorous and straightforward accompaniments from the LSO of the early ’60s‚ the puretoned soloist memorably elegant and suave. In place of the Sinfonia concertante included in the concertos’ current Philips Duo manifestation‚ we have a pair of sonatas from a celebrated set of six that Clara Haskil and Arthur Grumiaux taped in the late 1950s. The much younger Grumiaux may have been the junior partner‚ but the balance of the recording distorts their relationship; one has to listen through the violinist’s accompanimental passagework to access the main melodic material in the subtly articulated piano part.

Alan Civil’s full‚ round tone graces countless recordings. A Philharmonia principal from 1955‚ moving on to the BBC Symphony in 1966‚ he set down the Mozart Horn Concertos with Klemperer and Kempe as well as Marriner. Is there perhaps a sense of going through the motions in these avuncular‚ expertly crafted retreads? (Michael Thompson on Naxos is even cheaper and incorporates the latest scholarship‚ 8/98.) And for all that Neil Black’s Oboe Concerto sounds neat and newly minted‚ I’m not sure anything on this disc belongs in a series that purports to represent the best of Philips’ 50 years in the business. But then we could most of us make lists of supposedly grievous omissions.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.