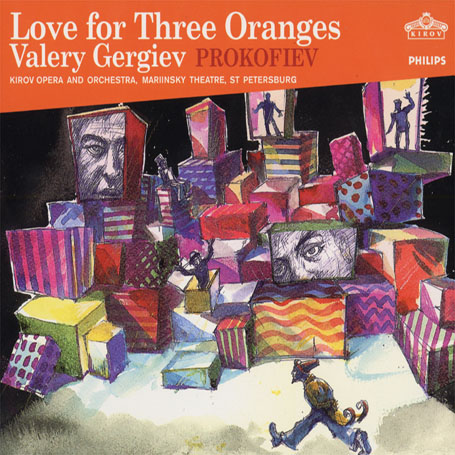

Prokofiev The Love of Three Oranges

The only complete recording of this work sung in Russian, and very fine it is, evoking all the work’s invention and subtlety

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Sergey Prokofiev

Genre:

Opera

Label: Philips

Magazine Review Date: 3/2001

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 102

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 462 913-2PH2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (The) Love for Three Oranges |

Sergey Prokofiev, Composer

Anna Netrebko, Truffaldino, Tenor Evgeny Akimov, Herald, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Linetta, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Linetta, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Celio, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Celio, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Celio, Bass Fyodor Kuznetsov, Linetta, Contralto (Female alto) Grigory Karasev, Pantalone, Baritone Kirov Opera Chorus Kirov Opera Orchestra Larissa Diadkova, Master of Ceremonies, Tenor Larissa Shevchenko, Prince, Tenor Lia Shevtsova, Leandro, Baritone Mikhail Kit, Smeraldina, Mezzo soprano Olga Korzhenskaya, Fata Morgana, Soprano Sergey Prokofiev, Composer Valery Gergiev, Farfarello, Bass Vladimir Vaneev, King of Clubs, Bass Yuri Zhikalov, Nicoletta, Mezzo soprano Zlata Bulycheva, Princess Clarissa, Contralto (Female alto) |

Author: David Fanning

Goldoni’s play of 1761, adapted by Meyerhold in 1914 and set by Prokofiev four years later, was in many respects way ahead of its time. As Lionel Salter pointed out in his review of the Lyon Opera recording under Kent Nagano, it prefigured not only Brecht but also the Theatre of Cruelty and the Theatre of the Absurd. Prokofiev fell with relish on the scenario, seeing in it an opportunity to puncture the pretensions of the opera house, rather as Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods, working from the opposite direction and with more meagre compositional resources, has more recently used fairy-tale in an attempt to add pretensions to the musical theatre.

Musically The Love for Three Oranges builds on Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel; and in turn Shostakovich’s The Nose seeks to build on Prokofiev. It’s a fabulously imaginative score, never reliant on cliche, always light on its feet and gloriously orchestrated. All credit to Gergiev and his Kirov players for provoking these observations. This is the fifth of their Prokofiev opera series, and it more than lives up to the high standards already set.

Among the evil conspirators at the court of the King of Clubs there are admittedly some dryish-sounding voices. But the main roles are superbly taken, most notably by tenor Evgeny Akimov as the whining, hypochondriac Prince (his malady, diagnosed at one point from an examination of his sputum, has been brought on by his over-exposure to ‘ancient, rotting verses and putrefying rhymes’). Other outstanding contributions come from Grigory Karasev as the giant cook who guards the Three Oranges, Feodor Kuznetsov as the demon Farfarello, and Anna Netrebko as the last of the three Princesses eventually released from the Oranges.

Although this is Prokofiev’s most popular opera, the only current rival complete recording is Kent Nagano’s. Like Gergiev he conducts a meticulously prepared account and one that is equally sharp in its etching of Prokofiev’s caustic wit. Though his cast displays less vocal distinction in the principal roles, there is more consistency in the minor ones. They sing in French, which was the language of the opera’s first performances in Chicago in 1920 (the composer himself collaborated on the translation). Given the nature of the story, the original Russian is perhaps less vital than with most of Prokofiev’s operas, and in many ways the very best way to experience the work is in the vernacular (it’s a minor scandal that Opera North’s wonderful production from the mid-1990s was never filmed). But it’s wonderful to have the choice between the Russian and French versions, each magnificently served; serious opera-collectors will ideally need to have both.

The Kirov recording was made live in Amstersdam in sessions spaced 10 months apart. I can’t say I was conscious of any joins, and the warmer ambience of the Concertgebouw amply compensates for the Maryinsky Theatre’s more concentrated atmosphere. Though there is a certain amount of variance in the miking of the voices, this is never more than the action itself invites. Inevitably the audience misses out on the visual element, which is more than usually crucial with this opera. Even so, some of the verbal and situational humour clearly gets across, and the applause is understandably tumultuous. I wonder if there is also to be a video of the recent Kirov production at the Maryinsky, of which the booklet gives us one tantalising photo?'

Musically The Love for Three Oranges builds on Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel; and in turn Shostakovich’s The Nose seeks to build on Prokofiev. It’s a fabulously imaginative score, never reliant on cliche, always light on its feet and gloriously orchestrated. All credit to Gergiev and his Kirov players for provoking these observations. This is the fifth of their Prokofiev opera series, and it more than lives up to the high standards already set.

Among the evil conspirators at the court of the King of Clubs there are admittedly some dryish-sounding voices. But the main roles are superbly taken, most notably by tenor Evgeny Akimov as the whining, hypochondriac Prince (his malady, diagnosed at one point from an examination of his sputum, has been brought on by his over-exposure to ‘ancient, rotting verses and putrefying rhymes’). Other outstanding contributions come from Grigory Karasev as the giant cook who guards the Three Oranges, Feodor Kuznetsov as the demon Farfarello, and Anna Netrebko as the last of the three Princesses eventually released from the Oranges.

Although this is Prokofiev’s most popular opera, the only current rival complete recording is Kent Nagano’s. Like Gergiev he conducts a meticulously prepared account and one that is equally sharp in its etching of Prokofiev’s caustic wit. Though his cast displays less vocal distinction in the principal roles, there is more consistency in the minor ones. They sing in French, which was the language of the opera’s first performances in Chicago in 1920 (the composer himself collaborated on the translation). Given the nature of the story, the original Russian is perhaps less vital than with most of Prokofiev’s operas, and in many ways the very best way to experience the work is in the vernacular (it’s a minor scandal that Opera North’s wonderful production from the mid-1990s was never filmed). But it’s wonderful to have the choice between the Russian and French versions, each magnificently served; serious opera-collectors will ideally need to have both.

The Kirov recording was made live in Amstersdam in sessions spaced 10 months apart. I can’t say I was conscious of any joins, and the warmer ambience of the Concertgebouw amply compensates for the Maryinsky Theatre’s more concentrated atmosphere. Though there is a certain amount of variance in the miking of the voices, this is never more than the action itself invites. Inevitably the audience misses out on the visual element, which is more than usually crucial with this opera. Even so, some of the verbal and situational humour clearly gets across, and the applause is understandably tumultuous. I wonder if there is also to be a video of the recent Kirov production at the Maryinsky, of which the booklet gives us one tantalising photo?'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.