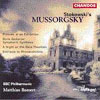

Mussorgsky (arr Stokowski) Orchestral Works

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Modest Mussorgsky

Label: Chandos

Magazine Review Date: 9/1996

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 69

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: CHAN9445

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (A) Night on the Bare Mountain |

Modest Mussorgsky, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Matthias Bamert, Conductor Modest Mussorgsky, Composer |

| Boris Godunov, Movement: Symphonic Synthesis (arr/orch Stokowski) |

Modest Mussorgsky, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Matthias Bamert, Conductor Modest Mussorgsky, Composer |

| Khovanshchina, Movement: Prelude (Scene 2) |

Modest Mussorgsky, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Matthias Bamert, Conductor Modest Mussorgsky, Composer |

| Pictures at an Exhibition |

Modest Mussorgsky, Composer

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Matthias Bamert, Conductor Modest Mussorgsky, Composer |

Author: Ivan March

In his excellent biography of Stokowski (Dodd and Mead: 1982) Oliver Daniel talks in detail of doubts expressed by various musicians that Stokowski’s orchestral transcriptions were entirely his own work. Certainly in the earlier days Lucien Cailliet (a clarinet player in the Philadelphia Orchestra) had a considerable hand in the Bach scores and he very likely did a good deal of the physical work of score-writing. Yet Cailliet himself stated that the conductor and he discussed each piece in detail first, and it is known that Stokowski was always amending the instrumentation in the course of performances. In any case, Cailliet’s association with the conductor ended in 1938 and while he might have contributed to the skilfully tailored 24-minute Boris Godunov synthesis (according to Daniel, dating from November 1936), the Pictures at an Exhibition (1939) was all Stokowski’s own and Night on Bald Mountain (the correct title, and nearer the original Russian meaning) was scored for Disney in 1940.

Anyone who has seen Fantasia finds the imagery in this last piece unforgettable and the powerfully plangent orchestration (especially the use of percussive effects) is in many respects nearer to Mussorgsky’sSt John’s Night on the Bare Mountain than the Rimsky version. It sounds really superb here, as indeed does the Pictures – far preferable to the bloated Phase 4 sound of Stokowski’s own earlier recordings for Decca. The sombre power of the operatic synthesis, with its Kremlin bells and chanting monks and the haunted portrait of Boris himself, emerges with distinction. The Entr’acte from Khovanshchina is even finer, one of Stokowski’s most effective transcriptions, rich in sonority and played very movingly under Matthias Bamert.

I like the vividness of Stokowski’s Pictures too, particularly the way in which the orchestration is varied – the unison horns sing out splendidly near the climax of “Bydlo”, while to feature a cor anglais for the main theme in “The old castle” is quite as telling as Ravel’s saxophone, perhaps more so. Stokowski uses the violins rather more than Ravel, as instanced by the opening “Promenade”. The one moment when Ravel’s scoring is truly inspired is the interchange between Goldenburg and Schmuyle; Stokowski has the woodwind echo the solo trumpet and the effect, mockingly piquant though it is, becomes less bleatingly obsequious than Ravel’s version. Not surprisingly the “Catacombes” sequence makes a sumptuously weighty impact and “Baba-jaga” is searingly grotesque and bizarrely full of imaginative orchestral comments. Two numbers are omitted: “Tuileries” and “Limoges”, as Stokowski considered them “too French” and “not Mussorgskian”. (Edward Johnson’s authoritative notes suggest that the conductor did not have access to the original piano score, but if not, what did he use to make his transcription?) “The Great Gate of Kiev”, scored for massive forces, including bells and organ, makes a huge final apotheosis – how Stokowski must have revelled in its grand climax.'

Anyone who has seen Fantasia finds the imagery in this last piece unforgettable and the powerfully plangent orchestration (especially the use of percussive effects) is in many respects nearer to Mussorgsky’s

I like the vividness of Stokowski’s Pictures too, particularly the way in which the orchestration is varied – the unison horns sing out splendidly near the climax of “Bydlo”, while to feature a cor anglais for the main theme in “The old castle” is quite as telling as Ravel’s saxophone, perhaps more so. Stokowski uses the violins rather more than Ravel, as instanced by the opening “Promenade”. The one moment when Ravel’s scoring is truly inspired is the interchange between Goldenburg and Schmuyle; Stokowski has the woodwind echo the solo trumpet and the effect, mockingly piquant though it is, becomes less bleatingly obsequious than Ravel’s version. Not surprisingly the “Catacombes” sequence makes a sumptuously weighty impact and “Baba-jaga” is searingly grotesque and bizarrely full of imaginative orchestral comments. Two numbers are omitted: “Tuileries” and “Limoges”, as Stokowski considered them “too French” and “not Mussorgskian”. (Edward Johnson’s authoritative notes suggest that the conductor did not have access to the original piano score, but if not, what did he use to make his transcription?) “The Great Gate of Kiev”, scored for massive forces, including bells and organ, makes a huge final apotheosis – how Stokowski must have revelled in its grand climax.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.