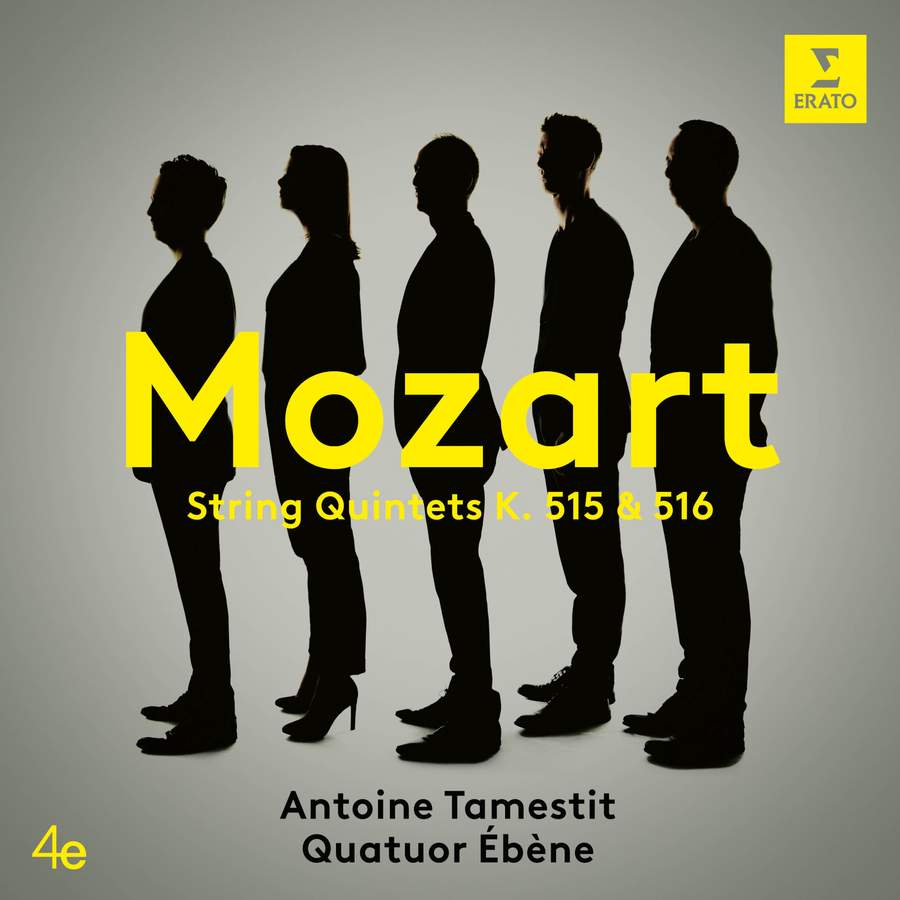

MOZART String Quintets K515 & K516

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Chamber

Label: Erato

Magazine Review Date: 04/2023

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 72

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 5419 72133-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| String Quintet No. 3 |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Composer

Antoine Tamestit, Viola Ébène Quartet |

| String Quintet No. 4 |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Composer

Antoine Tamestit, Viola Ébène Quartet |

Author: Richard Wigmore

Mozart’s most famous quintets conclude a sequence of four instrumental works from the winter and spring of 1786 87 whose first movements, at least, are on an unprecedentedly monumental scale: the Prague Symphony, the C major Piano Concerto, K503, and this complementary pair of string quintets, in C major, K515, and G minor, K516. Some 17 years before the Eroica Mozart had got there first, though revealingly he never again essayed the vast dimensions of these four masterpieces. In the quintets we can guess that the expansiveness was prompted both by the richness of sonority created by an additional viola and the increased opportunities for textural variety: say, at the opening of the G minor, where the long opening theme is presented first by the upper three strings and repeated, with an added sense of fatalism, by the lower three. The movement’s scale is already mapped out.

In a less than congested field, the standout recordings of Mozart’s quintets have been the venerable Philips set from Grumiaux and friends and the Nash Ensemble, 2010 vintage. The Quatuor Ébène and viola player Antoine Tamestit start with the advantage of a more transparent recording than either. This, allied to their care for balance, means that no detail of Mozart’s miraculous inner part-writing escapes the ear. In sheer technical polish, too, the augmented Ébène have the edge over their rivals.

As to interpretation, where the Grumiaux team and the Nash give strong, essentially Classical performances, the Ébène are more Romantically flexible. In the C major’s opening Allegro they and Grumiaux choose a comparably broad tempo, in contrast to the brisk, no-nonsense Nash. But the Ébène are more inclined to flex the pulse and vary their tone colour in response to harmony, as in the poetic dip to distant flat keys near the opening (from 1'11") or the mysteriously gliding sequences of the development (from 8'33"), where the Ébène seem to morph into an antique viol consort. Theirs is a performance con amore, yet without a whiff of indulgence. Cultivating a hushed, veiled tone, they make the strangely unstable Minuet unusually inward, even dreamlike. On the face of it they choose a dangerously slow tempo in the duetting Andante, a serene sequel to Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante. Yet the Ébène compel the ear with their beauty of tone and eloquence of line, with Pierre Colombet’s violin and Antoine Tamestit’s viola vying with each other in amorous tenderness.

From the pulsing opening bars of the C major Quintet the Ébène take special care with the shaping and balancing of routine-looking accompaniments. Everything has its own distinctive life in music that unfolds as a true democracy. In the Allegro of the G minor Quintet – arguably Mozart’s most depressive instrumental movement – they strike a fine balance between forward momentum and expressive yielding. As ever, they make you aware of the vocal nature of Mozart’s inspiration. Typically, the Nash are more urgent, emphasising agitation over pathos, though they score over both the Ébène and the Grumiaux by observing the second-time repeat, with the effect of throwing more weight on to the desolate coda.

The opening of the G major Trio, stealing in shyly after the minor-key close of the Minuet, is a characteristically magical moment from the Ébène. As in the C major, they choose a broad tempo for the Adagio, here shorn of Mozart’s ma non troppo qualification. But again they silence misgivings with their intensity and colouristic subtlety: from the prayerful opening, through the plunging disquiet of the B flat minor theme, with its cries of pain deep in the second viola, to the ecstatic release of the subsequent violin-viola duet, floated with exquisite delicacy by the Ébène.

Listeners used to the relative straightforwardness of the Grumiaux and Nash may initially find the Ébène’s playing micromanaged. Some will doubtless feel that the finale’s G minor Adagio introduction, taken Adagissimo, is over-milked for tragic import. As you’ll by now have gathered, I succumbed. In the G major Allegro that follows many commentators have accused Mozart of ducking out of the profound issues raised by the previous movements. Emerging, as if dazed, into the light, the Ébène distil a rarefied, slightly wistful playfulness, leaving a faint sense of ambiguity. Typically, apparently neutral accompanying figures dart and quiver with life. While it’s always dangerous to nominate an outright ‘winner’ in this inexhaustible music, the Ébène are second to none in colour and vitality, and unrivalled in their lyrical tenderness. For me they become a new benchmark.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.