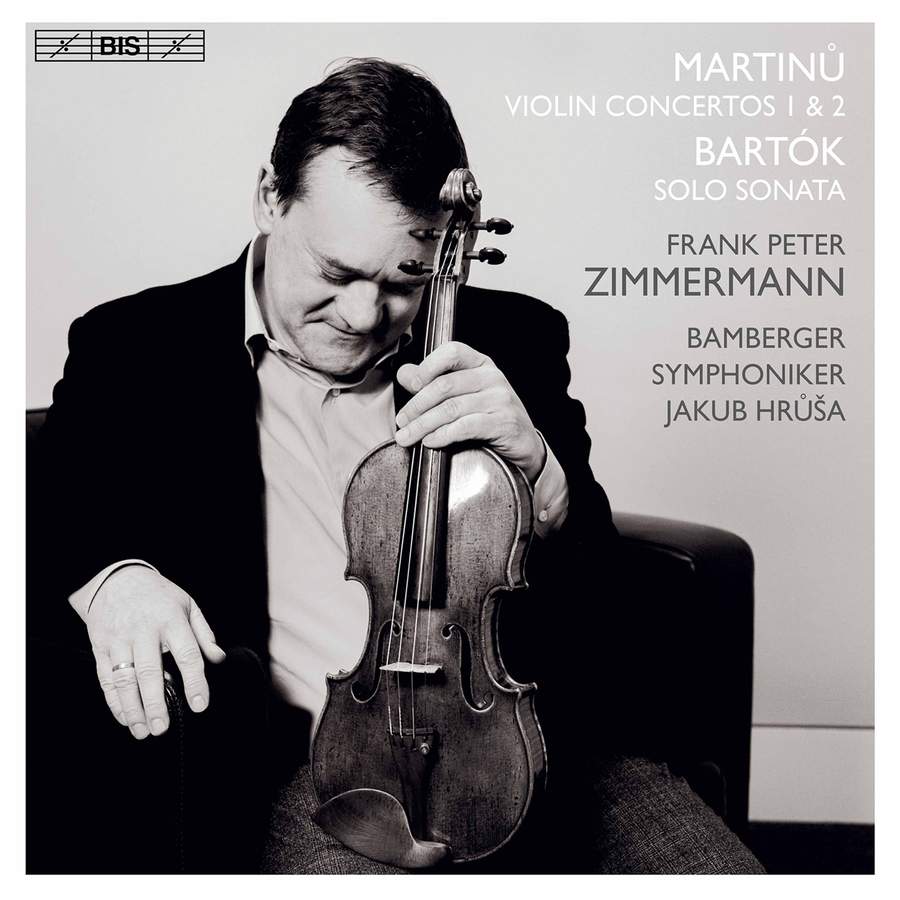

MARTINŮ Violin Concertos Nos 1 & 2 BARTÓK Sonata for Solo Violin (Frank Peter Zimmermann)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: BIS

Magazine Review Date: 01/2021

Media Format: Super Audio CD

Media Runtime: 74

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: BIS2457

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 |

Bohuslav (Jan) Martinu, Composer

Bamberger Symphoniker Frank Peter Zimmermann, Violin Jakub Hrusa, Conductor |

| Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1 |

Bohuslav (Jan) Martinu, Composer

Bamberger Symphoniker Frank Peter Zimmermann, Violin Jakub Hrusa, Conductor |

| Sonata for Solo Violin |

Béla Bartók, Composer

Frank Peter Zimmermann, Violin |

Author: Guy Rickards

Despite the eminence of the coupling of the Bartók Solo Sonata, the two Martinů concertos are the main event on this superbly engineered release. Their paths to public consciousness were markedly different from each other. The First Concerto was commissioned in 1932 by the Polish-American violinist Samuel Dushkin (1891-1976). Dushkin was fresh from his collaboration with Stravinsky for the latter’s Violin Concerto. Unlike Stravinsky, however, Martinů had been a professional violinist and knew what the instrument was capable of, but his view of the solo part was – and remained – sufficiently at variance with Dushkin’s for work to be abandoned in 1934. As Martinů had commented that ‘more work was needed’, the concerto was believed incomplete. The manuscript disappeared from view in the 1930s but found its way as part of the Moldenhauer Collection to the library of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where it was rediscovered by Harry Halbreich three decades later; the premiere – with Joseph Suk as soloist – followed in 1973. In the meantime, composer and commissioner worked awkwardly at a second commission, the Suite concertante, in 1939 but ended up with a second rather variant version five years later!

What put Dushkin off the First Concerto? It is written in the fashionable neoclassical style of the day, not so far away from that of the Stravinsky, but expressively quite different from it. However, the technical challenges of Martinů’s solo part are far greater, without necessarily appearing so. Any interpreter therefore needs to focus on the music’s irresistible flow (rather than showy virtuosity) and Zimmermann does this – I hesitate to say with ease – with consummate artistry. This performance, again, does not sound like a challenge to be overcome: rather a vibrant and hugely enjoyable piece of music. So, too, with the Second Concerto (for long believed to be Martinů’s sole contribution to the genre), a more genial and relaxed work commissioned at the end of 1942 by Mischa Elman and premiered at the end of the following year. Martinů maintained a strict distance between himself and Elman this time, which accounts in large part for the work’s straightforward route to the repertoire.

I surveyed the available rivals for the two concertos when welcoming Thomas Albertus Irnberger’s competitive accounts two years ago. These new interpretations by Frank Peter Zimmermann, however, go straight to the top of the pile. Throughout both concertos he evinces a sympathy with Martinů’s idiom that is, if anything, even stronger than Irnberger’s, a knowledge to rival Bohuslav Matoušek’s on Hyperion and a peerless technique.

Those competitors were Czech recordings but the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra has a notable pedigree in Czech music: the orchestra’s origins lie in an orchestra formed in Prague, after all, and readers may recall their very fine cycle of Martinů’s symphonies under Neeme Järvi (BIS, 9/87, 12/88). Their chief conductor Jakub Hrůša (together they were awarded the 2020 Bavarian State Prize for Music) is also principal guest conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and as fine a Martinů interpreter as anyone on the podium currently. What impresses most here, however, is the clarity and naturalness of Zimmermann’s performances, remarkable in combining an intimate knowledge of the music (the result of long study) with a freshness of approach. This is, for me, the top recommendation for these two works and, frankly, is how Martinů should always be played.

An obvious coupling would have been the Suite concertante (in either version), but Zimmermann has form in coupling concertos with unaccompanied works, as in his wonderful Hindemith album (9/13). Since Martinů never penned a solo violin sonata, Zimmermann turned to Bartók’s instead (which presumably means he will not be recording the concertos any time soon). This is a beautifully phrased account with a rhythmic precision and cleanness of sound that is second to none. The articulation is vital in what is one of the swiftest versions currently available, outpacing even James Ehnes’s brilliant account on Chandos. What commends Zimmermann’s performance above his rivals is his focus on the Bartók not as a daunting obstacle, requiring virtuosity for its own sake, but solely as magnificent music. His playing is less ferocious than Franziska Pietsch (who mightily impressed Rob Cowan two years ago), preferring a subtler, lighter approach – even more than Vilde Frang – which is entirely winning. Suffused with light, this is the most humane account of this work that I have encountered.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.