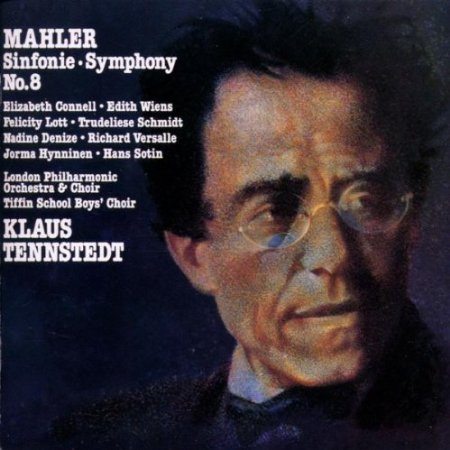

Mahler Symphony No 8

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Gustav Mahler

Label: EMI

Magazine Review Date: 3/1987

Media Format: Vinyl

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: EX270474-3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 8, 'Symphony of a Thousand' |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

Edith Wiens, Soprano Elizabeth Connell, Soprano Felicity Lott, Soprano Gustav Mahler, Composer Hans Sotin, Bass Jorma Hynninen, Baritone Klaus Tennstedt, Conductor London Philharmonic Choir London Philharmonic Orchestra Nadine Denize, Mezzo soprano Richard Versalle, Tenor Tiffin School Boys' Choir Trudeliese Schmidt, Mezzo soprano |

Author:

What would Mahler think of us sitting in our homes listening in a confined space to his ''planets and suns revolving'' in his Eighth Symphony? If ever a work was designed for an exhibition hall on a special festival occasion this was it. Yet, such is the miracle of modern recording techniques, it transfers well to the gramophone record, always allowing that a vital ingredient—that of a huge audience engrossed by the music—is missing. Most of us who love Mahler and aim to study him to the best of our ability have confessed to doubts about the Eighth; I keep changing my mind about it and am content to continue to do so; it is part of a continuous process of getting to grips with it.

It is gratifying to learn from Edward Seckerson's interview (see page 1237) that Klaus Tennstedt has no doubts about it. He conducts it in that frame of mind and he is so convincing that he may well sweep away others' doubts too. I can only say that when I listened first to this recording I was profoundly moved, almost to tears. It comes over, for all its immensity of scale, as a deeply intimate personal statement, not only from Mahler but from Tennstedt himself.

There is, of course, also the Solti/Decca recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra recorded in Vienna. That is still a marvellous achievement, artistically and technically, and anyone who possesses it really does not need another performance but ought to have this Tennstedt also because the two conductors' approach is very different and each is valid and successful. You will learn different things about the symphony from each performance.

Solti's is the more dynamic. His closing five minutes are apocalyptic, whereas Tennstedt's—slower but not too slow—are supplicating and ecstatic. The respective engineers have perfectly matched the character of both interpretations. The soloists and choir in Solti's are more forward and are very brightly recorded. For Tenndstedt they are—as he told Edward Seckerson he required—another and integrated strand in the orchestral texture. The effect is often surpassingly beautiful. I have not heard a performance of Part 1, ''Veni Creator Spiritus'', that better succeeds in being both strenuously massive and lyrically relaxed. Take the passage from fig. 19, where the voices sound like the bells in the orchestra and the solo violin's delicate figurations are like detail in a great religious painting.

Solti's soloists are perhaps individually superior, but Tennstedt and the engineers score in Part 2 with their placing of Felicity Lott so that the Mater Gloriosa's rapturous solo seems to reach our ears from another sphere. I also very much like the tenor Richard Versalle's singing of Doctor Marianus.

But the glory of this recording is the playing of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the singing of the London Philharmonic Choir and the Tiffin School Boys' Choir. Woodwind chording near the start of Part 2 is exceptionally fine, and the strings' playing throughout—but especially from fig. 96 to 100—is of a richness and tenderness that even Solti's Chicagoans cannot match. The choir's diction is outstanding and the contrapuntal passages in Part 1 are clearly defined. Obviously the decision to have a smaller choir for recording purposes was wise and has led to unusual clarity at the climax of the development. And there is no sacrifice in volume—the return of the ''Creator Spiritus'' theme in the recapitulation is overwhelming. The Westminster Cathedral organ has evidently been dubbed on to the recording highly successfully. Such 'cheating' is justified, for one must have that kind of organ-sound in this work.

Tennstedt's scrupulous regard for dynamics is a feature of the performance. When Mahler has called for pppp, that is really what Tennstedt gives him. Listen, too, for the lovely phrasing of the Adagissimo theme at its first appearance (fig. 106) and the ideal balance between choir and harps (beautifully played here, as they are at the magical Ruhig at 197). I could go on, but this is the finest of the Tennstedt cycle and one of the superlative Mahler performances on record.'

It is gratifying to learn from Edward Seckerson's interview (see page 1237) that Klaus Tennstedt has no doubts about it. He conducts it in that frame of mind and he is so convincing that he may well sweep away others' doubts too. I can only say that when I listened first to this recording I was profoundly moved, almost to tears. It comes over, for all its immensity of scale, as a deeply intimate personal statement, not only from Mahler but from Tennstedt himself.

There is, of course, also the Solti/Decca recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra recorded in Vienna. That is still a marvellous achievement, artistically and technically, and anyone who possesses it really does not need another performance but ought to have this Tennstedt also because the two conductors' approach is very different and each is valid and successful. You will learn different things about the symphony from each performance.

Solti's is the more dynamic. His closing five minutes are apocalyptic, whereas Tennstedt's—slower but not too slow—are supplicating and ecstatic. The respective engineers have perfectly matched the character of both interpretations. The soloists and choir in Solti's are more forward and are very brightly recorded. For Tenndstedt they are—as he told Edward Seckerson he required—another and integrated strand in the orchestral texture. The effect is often surpassingly beautiful. I have not heard a performance of Part 1, ''Veni Creator Spiritus'', that better succeeds in being both strenuously massive and lyrically relaxed. Take the passage from fig. 19, where the voices sound like the bells in the orchestra and the solo violin's delicate figurations are like detail in a great religious painting.

Solti's soloists are perhaps individually superior, but Tennstedt and the engineers score in Part 2 with their placing of Felicity Lott so that the Mater Gloriosa's rapturous solo seems to reach our ears from another sphere. I also very much like the tenor Richard Versalle's singing of Doctor Marianus.

But the glory of this recording is the playing of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the singing of the London Philharmonic Choir and the Tiffin School Boys' Choir. Woodwind chording near the start of Part 2 is exceptionally fine, and the strings' playing throughout—but especially from fig. 96 to 100—is of a richness and tenderness that even Solti's Chicagoans cannot match. The choir's diction is outstanding and the contrapuntal passages in Part 1 are clearly defined. Obviously the decision to have a smaller choir for recording purposes was wise and has led to unusual clarity at the climax of the development. And there is no sacrifice in volume—the return of the ''Creator Spiritus'' theme in the recapitulation is overwhelming. The Westminster Cathedral organ has evidently been dubbed on to the recording highly successfully. Such 'cheating' is justified, for one must have that kind of organ-sound in this work.

Tennstedt's scrupulous regard for dynamics is a feature of the performance. When Mahler has called for pppp, that is really what Tennstedt gives him. Listen, too, for the lovely phrasing of the Adagissimo theme at its first appearance (fig. 106) and the ideal balance between choir and harps (beautifully played here, as they are at the magical Ruhig at 197). I could go on, but this is the finest of the Tennstedt cycle and one of the superlative Mahler performances on record.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.