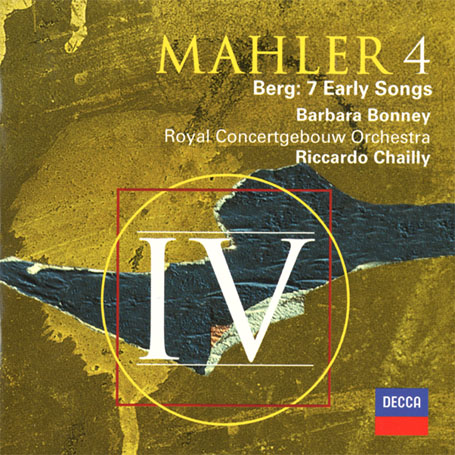

Mahler Symphony 4 & Berg 7 Early Songs

Texts and translations included A typical Chailly Mahler recording - beautifully observed, beautifully played but slightly cool in its approach

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Gustav Mahler, Alban Berg

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 4/2000

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 74

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 466 720-2DH

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 4 |

Gustav Mahler, Composer

(Royal) Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Alexander Kerr, Violin Barbara Bonney, Soprano Gustav Mahler, Composer Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

| (7) Frühe Lieder |

Alban Berg, Composer

(Royal) Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Alban Berg, Composer Barbara Bonney, Soprano Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

Author: David Gutman

When these performers launched the Concertgebouw's current season with Mahler's Fourth, it was only to be expected that Decca would be on hand to tape the results. On that occasion, the programme included the Altenberg Lieder, so perhaps these too will appear before long. As with his recording of the Fifth Symphony (Decca, 4/98), Riccardo Chailly follows hard on the heels of Daniele Gatti, and, if Chailly's is ultimately the less radical account, both interpretations inhabit an uneasy, twilight world, far removed from the lithe neo-classicism of Benjamin Britten. The Italians are broadly in agreement over how the symphony should be launched, flutes and sleighbells being wholly independent of the clarinets' and first violins' ritardando, an effect no longer uncommon on record. In an interview with the Dutch journalist Roland de Beer, Chailly has drawn particular attention to his studies of Mengelberg's copies of the Fourth and Seventh Symphonies. And yet Mengelberg's way with the opening remains unique, the first violins' quavers taken extremely slowly ('As if starting a Viennese waltz in Vienna, 'he reports Mahler as saying). Sensibly, Chailly divides his violins left and right, so that antiphonal effects register clearly (sample, if you can, from 6'35'').

Like Mengelberg, Chailly takes the second movement at quite a speed (compare Mengelberg's 8'17'' with Gatti's 11'11'') but, as usual, the detail is scrupulously observed. Every 'i' is dotted and every 't' crossed, the listener made aware of each unexpected shift of tempo and dynamic, each textural dislocation. For once, the solo violin's single semiquavers from 3'36'' (three bars after fig 6) really do sound 'very short and snatched, torn', the heel of the bow digging hard into the string. Elsewhere, Alexander Kerr is typically elegant, and you may feel that the scordatura tuning is supposed to catch more of a sense of unease. It certainly does with Gatti.

Such details apart, the quality of the orchestral playing does rather highlight the shortcomings of the RPO. The Dutch strings in particular are wonderfully lustrous in the slow movement, although triple pianos don't always register as they should and the intonation of the harmonics at the very end is surprisingly approximate. Chailly sets out at an ideally flowing poco adagio, and his conducting could never be described as laboured, for all the greater deliberation and higher seriousness that follows - the orchestral response is too sensitive. Still, the cellos' melody at 8'02'' struck me as over-phrased, Chailly transgressing the spirit of the score by sticking too rigidly to its letter.

I had been expecting the mood to lighten in the finale but it doesn't really. Not only does Chailly launch it rather limply (he is no match for Davis here), the wonderful Barbara Bonney seems unnaturally restrained, even a bit miserable. One can overlook the heavily aspirated semiquavers of 'himmlischen' - Bonney going for the adolescent peasant effect even though Mahler marks the whole phrase legato - and she takes 'Sankt Peter im Himmel sieht zu!' comfortably in one breath. Alas, however technically adroit her singing, Chailly's cool, firm hand on the tiller rather inhibits the 'final attainment of heavenly innocence', as Donald Mitchell puts it in his stimulating note. The final thrumming of the harp is a superbly articulated gesture, rather than a blissful leave-taking.

To these ears, Bonney and Chailly sound more at home in the post-Wesendonck idiom of the Berg. There is more of the warmth eschewed in the Mahler, and no risk of the soprano being swamped as can happen in live performance. The comparable alternative from Anne Sofie von Otter and Claudio Abbado is part of an all-Berg collection with a much less generous playing time. Jessye Norman and Pierre Boulez operate on a larger scale altogether, combining operatic amplitude with expressionistic colour.

How to sum up? Chailly's clear-sighted, weighty reading of the main work is blessed with superlative playing and top-notch sound, resonant yet detailed. If in the final analysis other interpreters are more distinctive, none offers such a stimulating coupling. Those who prize Chailly's not dissimilar recording of the Fifth will not hesitate. And even if you hanker after more temperament in your Mahler, the Berg songs are a splendid bonus, characteristic of this conductor's imaginative programming.'

Like Mengelberg, Chailly takes the second movement at quite a speed (compare Mengelberg's 8'17'' with Gatti's 11'11'') but, as usual, the detail is scrupulously observed. Every 'i' is dotted and every 't' crossed, the listener made aware of each unexpected shift of tempo and dynamic, each textural dislocation. For once, the solo violin's single semiquavers from 3'36'' (three bars after fig 6) really do sound 'very short and snatched, torn', the heel of the bow digging hard into the string. Elsewhere, Alexander Kerr is typically elegant, and you may feel that the scordatura tuning is supposed to catch more of a sense of unease. It certainly does with Gatti.

Such details apart, the quality of the orchestral playing does rather highlight the shortcomings of the RPO. The Dutch strings in particular are wonderfully lustrous in the slow movement, although triple pianos don't always register as they should and the intonation of the harmonics at the very end is surprisingly approximate. Chailly sets out at an ideally flowing poco adagio, and his conducting could never be described as laboured, for all the greater deliberation and higher seriousness that follows - the orchestral response is too sensitive. Still, the cellos' melody at 8'02'' struck me as over-phrased, Chailly transgressing the spirit of the score by sticking too rigidly to its letter.

I had been expecting the mood to lighten in the finale but it doesn't really. Not only does Chailly launch it rather limply (he is no match for Davis here), the wonderful Barbara Bonney seems unnaturally restrained, even a bit miserable. One can overlook the heavily aspirated semiquavers of 'himmlischen' - Bonney going for the adolescent peasant effect even though Mahler marks the whole phrase legato - and she takes 'Sankt Peter im Himmel sieht zu!' comfortably in one breath. Alas, however technically adroit her singing, Chailly's cool, firm hand on the tiller rather inhibits the 'final attainment of heavenly innocence', as Donald Mitchell puts it in his stimulating note. The final thrumming of the harp is a superbly articulated gesture, rather than a blissful leave-taking.

To these ears, Bonney and Chailly sound more at home in the post-Wesendonck idiom of the Berg. There is more of the warmth eschewed in the Mahler, and no risk of the soprano being swamped as can happen in live performance. The comparable alternative from Anne Sofie von Otter and Claudio Abbado is part of an all-Berg collection with a much less generous playing time. Jessye Norman and Pierre Boulez operate on a larger scale altogether, combining operatic amplitude with expressionistic colour.

How to sum up? Chailly's clear-sighted, weighty reading of the main work is blessed with superlative playing and top-notch sound, resonant yet detailed. If in the final analysis other interpreters are more distinctive, none offers such a stimulating coupling. Those who prize Chailly's not dissimilar recording of the Fifth will not hesitate. And even if you hanker after more temperament in your Mahler, the Berg songs are a splendid bonus, characteristic of this conductor's imaginative programming.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.