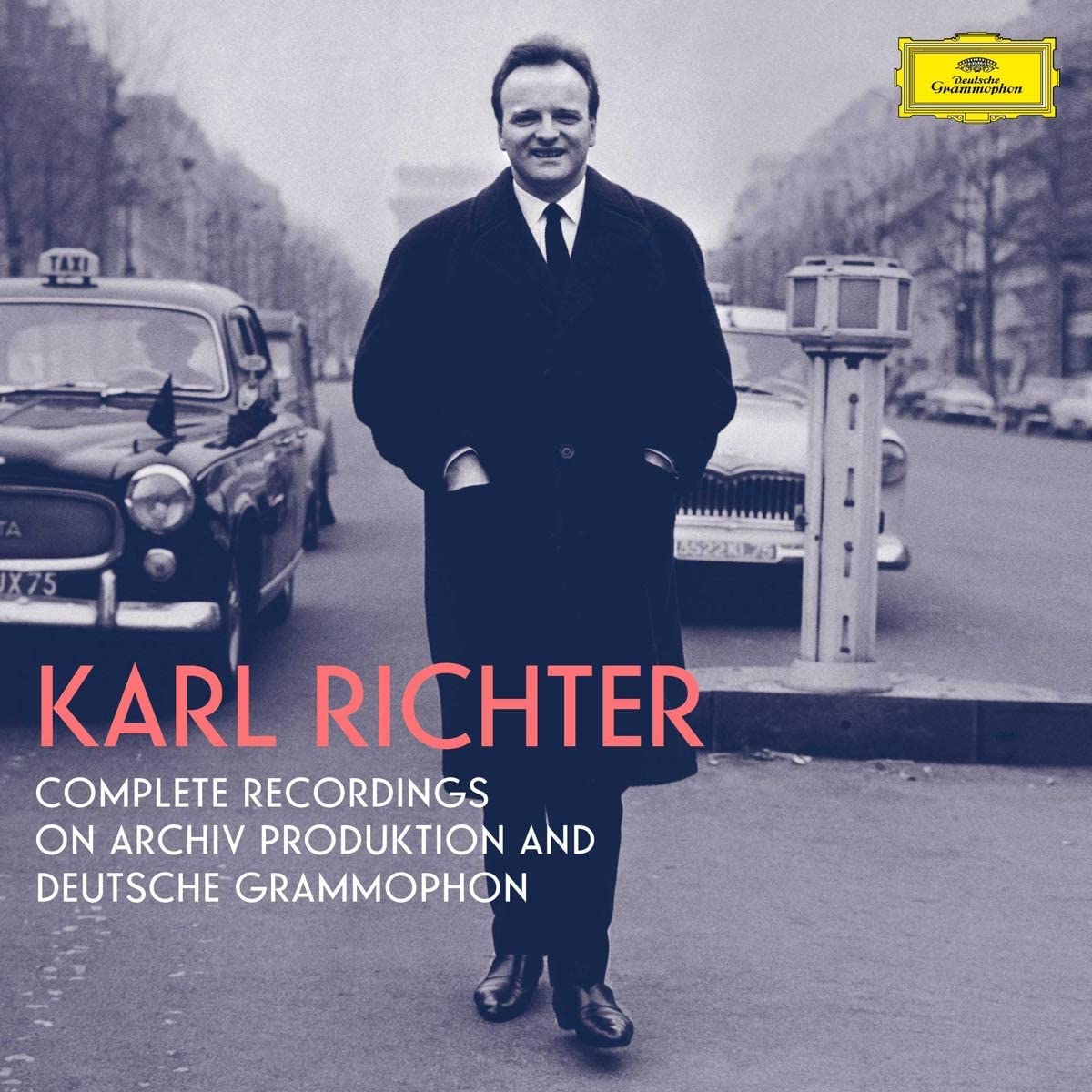

Karl Richter : Complete Recordings on Archiv Produktion and Deutsche Grammophon (97 CDs)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Magazine Review Date: 02/2021

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime:

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 483 9068

Author: Jonathan Freeman-Attwood

The summa totalis of Karl Richter’s DG recordings (from 1959 to 1980) affords us the greatest sense yet of an exceptional and pivotal figure in the post-war studio. Forty years after his death, Richter still divides opinion. At the start of his career, he was the byword for pioneering ‘authenticity’ – a Lutheran pastor’s son, partly reared at St Thomas’s in Leipzig, who was viewed by many as a kind of modern-day reincarnation of Bach and a beacon of hope in the demoralising aftermath of the war. As one of the great keyboard talents of his age and conductor-founder of the Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra, Richter’s spiritual zeal, precision and muscular virtuosity offered a radical alternative to the many soft-centred and tired-sounding Bach performance practices of the 1940s and ’50s. For someone whose work was centred primarily on Bach (exactly two-thirds in this box), Richter survived long enough to know that towards the end his values were being challenged by a new ideal of ‘authenticity’: the ‘period’ revolution was gathering steam under his very nose at Archiv – the label that had dominated his recording career – and from the late 1970s to his death in 1981 at the age of only 54, Richter ‘left the world an embittered man’, in the words of Nicholas Anderson.

John Eliot Gardiner’s damning description of Richter’s Bach, in his book Music in the Castle of Heaven, as ‘grim, sombre, po-faced, lacking in spirit, humour and humanity’ feels very wide of the mark on the evidence of this collection of 97 CDs and three Blu-ray Audio discs. Albeit from a different era, Richter regularly advances musical insights that are both profoundly illuminating and joyous, and with an unusual inward purity and honesty, even a naivety, that is bursting with humanity. His recorded oeuvre is certainly strikingly inconsistent, and it appears especially so now when changing fashions can curiously move us closer and further away from Richter at the same time. One imagines the same to be partly true of Herbert von Karajan, the other of those prolific DG maestros on the yellow label from this period. To add to an enigma of contradictions, despite his disapproval of Richter, Gardiner’s own Mass in B minor from 1985 (on the same label) moves, consciously or otherwise, towards the visceral and large-limbed territory Richter had recently vacated.

Not dissimilar to Karajan, Richter’s greatest strengths and failings rest on the unequivocal decisions at the heart of every interpretation. Each disc here offers a richly coloured perspective, rarely diluted by either distraction or nonchalance. Richter applies a hierarchy of musical characteristics which can either grip the listener in fervent emotional engagement or lose him/her in muffled heft. Rarely does an interpretation leave you feeling indifferent. If that’s the archetypal curate’s egg – and in general Richter’s recorded output becomes less, rather than more, distinguished over the years – the mystique of the man is never far beneath the surface. In his heyday, Richter the echt master-craftsman was famously indefatigable. Living on his nerves as he gave virtuoso organ and harpsichord recitals at the same time as playing the charismatic Kapellmeister, his reputation spread fast from Europe to the US, South America, the USSR and Japan, where he achieved a status not that far behind Glenn Gould, in Bachian terms at least.

In 1995 Teldec released a box of Richter’s early forays from the mid-1950s – a combination of cantatas, Passions and solo keyboard music – but the choral recordings especially feel like a man gathering his materials for the serious DG journey to come: only a glorious trio of cantatas (Nos 67, 108 and 127), including an evergreen Peter Pears from 1959, and a characterful set of Handel organ concertos can stand alongside the best from this new collection. In fact, DG had started to record the Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra shortly before, a contract that was to run alongside Telefunken (as Teldec then was) until such time as Richter was given free rein on the yellow and silver labels.

To enjoy Richter’s Bach, you have to submit to intellectual and emotional values quite alien to the sensibilities, conceits and inflections of what has become our historical-performance mainstream. Musical truth for Richter is about the intense and direct projection of the text as he reads it. You see it in those burning eyes, shooting the meaning of the Word with a fervour, nobility and sense of architecture that unashamedly imbue in every sinew of Richter’s being from his first down-beat. From this early period, the 1958 recording of the St Matthew Passion remains a gold standard. The final half an hour has never been bettered, complete with Fischer-Dieskau’s unforgettable ‘Mache dich’ and the abject sorrow of the final chorus. The 1979 reading is a mawkish reflection of Richter’s enervating last years, with its interminable tempos and over-embellished continuo.

In 2018 DG released Richter’s 75 cantatas – the majority recorded in the 1970s and grouped in seasons rather than cycles – in a satisfyingly compact 24-bit Blu-ray edition and they sound wonderfully sprung, with the superb balance that characterised the engineering from which Richter benefited throughout his career. Revisiting many of these performances, one is struck repeatedly by the distinction, if not always the ideal judgement, of the solo singing and almost unreservedly by the supreme obbligato playing. Richter had the magnetism to attract the very best that the Continent could offer, hence the likes of flautist Aurèle Nicolet, oboists Edgar Shann and Manfred Clement, the horn player Hermann Baumann and the trumpeter Maurice André. The latter is unforgettable in the celebrated Christmas Oratorio with Gundula Janowitz, Fritz Wunderlich et al from 1965.

If Fischer-Dieskau is ubiquitous, he is the one singer of the ‘very regulars’ (the bombproof Edith Mathis is another in this category) who can drift into automatic pilot, relying too much on his celebrated timbre and over-seasoned mannerisms. More in thrall to Richter’s direction are the tenors Ernst Haefliger and Peter Schreier, who cover almost the whole of Richter’s Bach discography. One of the glories of the latter years is the contralto Anna Reynolds, who offers a natural line and depth of sentiment that only Helen Watts (sadly, never a Richter recruit) can muster in Bach recordings of this era. The Advent, Christmas and earlier-recorded Trinity cantatas represent the pick of the bunch. Out of the 75 cantatas, at least 75 per cent contain something memorable. From this period, only Fritz Werner and the smaller output of Helmut Winschermann can really rival Richter for depth and range.

The instrumental Bach recordings are full of hits and misses. Several of them are new to CD, including a suffocating Goldberg Variations best left in its dust jacket. The finest keyboard work is dazzling – a good number of the harpsichord concertos, especially with his trusty lieutenant Hedwig Bilgram, and several of the organ preludes and toccatas. The F major Toccata from Freiburg Cathedral is awe-inspiring with its architectonic growth, rhetorical swagger and just its sheer brilliance. Helmut Walcha and Ralph Kirkpatrick respectively took the lion’s share of Archiv’s organ and harpsichord fare but there is enough here for Richter, especially alongside his earlier forays on Telefunken. The Brandenburgs and Orchestral Suites are executed with extraordinary aplomb and bravura, though with modern ears they are likely to be admired in small doses. The pleasant surprises I had failed to pick up (in so-called ‘licensed’ releases during trips to Japan) include the six sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord with Wolfgang Schneiderhan. There’s a theatrical flair and narrative that imparts a very different starting point to the music-making of today and yet, despite the gothic undertows in the allegros, there are moments of deeply felt poetic duetting.

The non-Bach recordings are dominated by an extraordinary miscellany of delectable surprises from Schütz to Reger (though not Bruckner, where he started his orchestral conducting career). Not many of them, alas, involve Handel, which is a shame given how much Handel he recorded. As was de rigueur at the time, countertenor opera roles were often taken by baritones, of which the most egregious example is Fischer-Dieskau in the title-role of Giulio Cesare. Yet the problem lies more fundamentally with Richter. He seems to eschew those characteristics that bring Handel’s music alive: elegance, sprightliness, humour (I’m with Gardiner here) and heart. His two Messiahs with his own forces and the LPO stubbornly avoid Handel’s penchant – even in his sacred works – for entertainment. That Richter stayed rigidly on his own mono-dramatic Handelian course is born out in his weighty set of Op 6 Concertos, although this fastidiously compiled box (it even includes a disc where it says that it was unlikely Richter was present at the sessions!) includes the Fritz Lehmann Op 6 set from 1952 in which a young Richter plays continuo; if only the apprentice could have absorbed the older man’s shaping and whim. There is one Handelian exception to relish: the Fireworks Music and two Due cori concertos in which the English Chamber Orchestra appear to have made a pact with Richter to leave them to ‘do their stuff’. The result is greater fluency, bounce and tenderness, the latter apparent in an enchanting Largo from the F major Concerto. Less than a decade later, we had Trevor Pinnock’s Handel concerto recordings – again on the same label – and we never looked back.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.