HUMPERDINCK Königskinder (Albrecht)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Opera

Label: Naxos

Magazine Review Date: AW23

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 175

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 2 110759

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Königskinder |

Engelbert Humperdinck, Composer

Daniel Behle, King's Son, Tenor Danish National Opera Chorus Doris Soffel, Witch, Mezzo soprano Josef Wagner, Fiddler, Baritone Marc Albrecht, Conductor Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra New Amsterdam Children's Choir Olga Kulchynska, Goose Girl, Soprano |

Author: Andrew Mellor

There aren’t many operatic scores with the consistent beauty, embrace, virility and honesty of Königskinder that remain effectively outside the repertoire. Don’t think of this as Humperdinck’s ‘difficult second album’ after Hänsel und Gretel; think of it as a more mature, multifaceted, flavoursome, theatrically scored and, yes, problematic work but one that holds its true wonders back until you’ve proved your loyalty as a listener.

I’ve been listening obsessively for years to Armin Jordan’s Montpellier recording (starring Jonas Kaufmann) and to Sebastian Weigle’s more urgently theatrical Frankfurt account led by Daniel Behle, also the tenor here (Accord and Oehms, both 12/13). I confess I hadn’t the faintest idea what they were singing about until this DVD arrived, and was in bits by the end. In the finest northern European tradition, this is a fairy tale whose bleak ending leaves the faintest residual hope at best (much like the Grimms’ Hänsel before Humperdinck’s sister got to work on it).

That delicate flame of optimism is further dampened by real events. The librettist who eventually sanctioned Humperdinck’s conversion of the score from a Singspiel to a through-sung opera for the Met in 1910 was Jewish and female. She was forced to disguise herself nominally as both man and Gentile when working on the piece, which dares to hope that in the distant future, goodness might prevail over evil. It was a future that proved too distant for Elsa Bernstein-Porges (aka Ernst Rosmer), who was sent to Theresienstadt, where her sister perished. The story is of an unassuming young pair who would by rights be king and queen had the general public liked better the cut of their jib. They are abused and cast out, dying in the closing minutes to fulfil the prophecy of the girl’s crone-like adoptive mother. A ghostly children’s chorus bids us remember them as the curtain falls. If you think of Hänsel as Humperdinck’s Parsifal, Königskinder is his Tristan – minus any sense of moral or philosophical victory. It’s easy to see why, in the long term, the Americans would have preferred … well, just about anything.

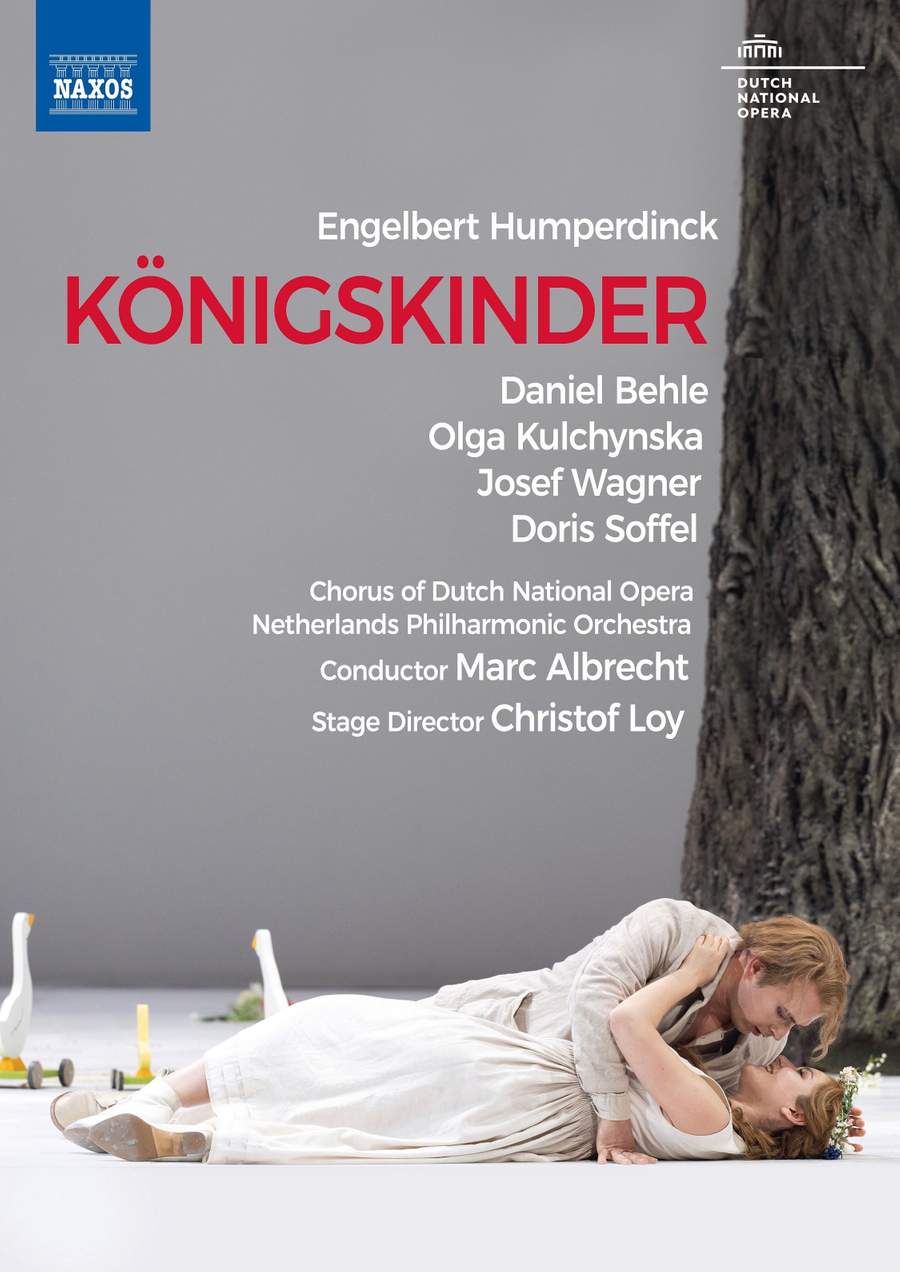

Christof Loy’s production for Dutch National Opera gives it to us pretty straight, but with a stark and timeless beauty that faintly references the Holocaust while reminding us to trust the next generation even against our own instincts. Humperdinck’s exquisite violin solos are played on stage by an acting Camille Joubert, who is listed among the dramatis personae as ‘Love’, which seems about right. Loy offers a moving, stylised silent movie with full-screen captions to bridge the chronological gap between Acts 2 and 3, and conductor Marc Albrecht has the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra draw out the Prelude to Act 3 so that, in every sense, it fits what we see.

Despite Loy’s typically disciplined colour palette and the sotto voce sophistication of Johannes Leiacker’s designs, never are we not being told a fairy tale. Olga Kulchynska’s Goose Girl plays around with toy geese on wheels; the Ukrainian soprano has that ability, so essential for Humperdinck, to elasticate a phrase. When Daniel Behle’s King’s Son meets her, you see in his eyes that he is changed for ever; his boyish tenor isn’t the most lustrous but he’s inside every phrase. Doris Soffel’s timeless Witch is dramatically brilliant; she kicks toys out of her way while lighting cigarettes and blowing smoke rings through them (ditto Kai Rüütel as the Innkeeper’s Daughter, her face a constant picture). You come to feel even for the Witch, but most of all for Josef Wagner’s Minstrel – one of opera’s few unsullied good guys – sung with oaky nobility and devastating in his dramatic trajectory from happy-go-lucky to hollowed-out.

Loy deftly deploys a small group of dancers. Sometimes they barely move at all and just look on in horror. On Europe’s widest operatic stage, they prove particularly useful in the desolate final scene, when all the lead couple can do is lie down and die. So convincing, so genuine is this passage that you feel, in the moment, as though nobody but Humperdinck could have got within touching distance of the required musical expression – that hallowed combination of depth and simplicity. Then again, he works equal magic, in an entirely different context, as his orchestra writhes and snorts at the start of Act 2 when the King’s Son arrives at a pig farm (so that’s what all those twisting woodwinds are about: turning stomachs). Nothing wrong with the conducting, and my only quibble would be a slightly underpowered children’s chorus. Otherwise, utterly captivating – every single second of it.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.