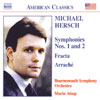

Hersch Symphonies Nos 1 and 2

Grand sweeps of musical cliché from a late bloomer

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Michael Hersch

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: American Classics

Magazine Review Date: 2/2007

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 64

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: 8 559281

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No 2 |

Michael Hersch, Composer

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Michael Hersch, Composer |

| Fracta |

Michael Hersch, Composer

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Michael Hersch, Composer |

| Symphony No 1 |

Michael Hersch, Composer

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Michael Hersch, Composer |

| Arraché |

Michael Hersch, Composer

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Michael Hersch, Composer |

Author: Philip_Clark

Brahms was knocking the big 4-0 when he wrote his first symphony; American composer Michael Hersch is now 35 and has written two, although I don't believe a note of them. “Anguished…searing yet breathtaking”, “harrowing and intense” and, bizarrely, a “late bloomer and a prodigy” are the quotes Naxos has chosen to promote his music, and perhaps the company is sending us a subliminal message. Hersch's symphonies are written in grand sweeps of cliché that freeload from Mahler and Berg shamelessly, reducing the gestural palette of these great composers into tepid patterning.

Perhaps I'm being too harsh. It's plain that Hersch can navigate around the orchestra like he knows the way around his own house. His harmonic language rejects fashionable post-minimalist doodling in favour of a not-unoriginal tonal patois that's spiced by embedded tone-clusters. But as his First Symphony (1998) begins with tubular bells supposedly symbolic of death and then hurtles into turgid, self-important string counterpoint, his vocabulary sounds decidedly second-hand. The Second Symphony (2001) begins with an explosion that provides enough energy to motor the music onwards; the third movement obsesses over a banal tune while abrupt insertions of material keep dramatic contrast in our minds even if, in reality, the material can't deliver.

Fracta (2002) and Arraché (2004) are marginally better because Hersch doesn't feel shackled by the expectations of the symphony. But he's feeding orchestras with what they already know, rather than subjecting our institutions to a post mortem and seeing what can be rescued from the bones.

Perhaps I'm being too harsh. It's plain that Hersch can navigate around the orchestra like he knows the way around his own house. His harmonic language rejects fashionable post-minimalist doodling in favour of a not-unoriginal tonal patois that's spiced by embedded tone-clusters. But as his First Symphony (1998) begins with tubular bells supposedly symbolic of death and then hurtles into turgid, self-important string counterpoint, his vocabulary sounds decidedly second-hand. The Second Symphony (2001) begins with an explosion that provides enough energy to motor the music onwards; the third movement obsesses over a banal tune while abrupt insertions of material keep dramatic contrast in our minds even if, in reality, the material can't deliver.

Fracta (2002) and Arraché (2004) are marginally better because Hersch doesn't feel shackled by the expectations of the symphony. But he's feeding orchestras with what they already know, rather than subjecting our institutions to a post mortem and seeing what can be rescued from the bones.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.