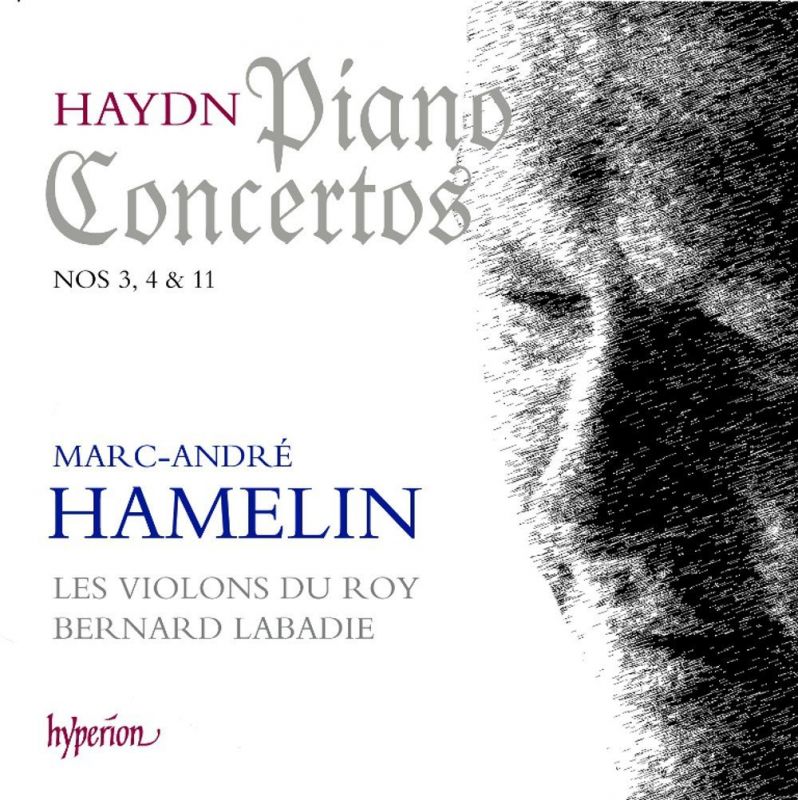

HAYDN Keyboard Concertos Nos 3, 4 & 11

Delight in a new recording of Haydn’s three keyboard concertos

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Joseph Haydn

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Hyperion

Magazine Review Date: 05/2013

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 61

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: CDA67925

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Keyboard and Orchestra |

Joseph Haydn, Composer

(Les) Violons du Roy, Québec Bernard Labadie, Conductor Joseph Haydn, Composer Marc-André Hamelin, Musician, Piano |

Author: David Threasher

These are the three indubitably authentic keyboard concertos of Joseph Haydn: No 3 in F, the earliest, possibly even dating from before Haydn’s employment with the Esterházy family; No 4 in G, audibly a later, harmonically richer work and one which was performed by the blind pianist Maria Theresia von Paradis (also the recipient of Mozart’s K456) in Paris in 1784; and No 11 in D, the best-known and most advanced of the three, composed some time between 1779 and 1783. Comparison is often made (not in Haydn’s favour) with the piano concertos of Mozart; and while it’s true that they don’t display the melodic generosity or orchestral richness of Mozart’s miraculous string of Vienna piano concertos of the 1780s, Haydn could not have heard those works before writing even the latest of his three, the D major. That’s not to say, however, that Haydn’s keyboard concertos are primitive or suffer from paucity of imagination, either thematically or orchestrally. Enjoy these works on their own terms and they’re every bit as rewarding in their own way as, say, Mozart’s K414 (1782).

Andsnes’s Award-winning disc was notable, among many other fine attributes, for the crystalline clarity of his fingerwork, especially in all those stretches of almost minimalistic patterning and the runs and scalic passages that are such a feature of this music. Naturally Hamelin is no slouch either – hardly surprising, given that the sort of virtuosity called for here is no more difficult than rolling over in bed for players of this exalted calibre. Listen, though, to the way Hamelin almost ‘falls into’ the runs towards the end of the first movement of the G major Concerto (No 4), then picks up on them for his (own) cadenza.

In fact, the cadenzas are among the special joys of this new disc. Hamelin’s reference points range, I’d say, from Bach up to Beethoven or thereabouts in the two earlier concertos – with perhaps a light dusting of Saint-Saëns in the F major’s slow movement – while Andsnes’s cadenzas (also his own) are in every case shorter and perhaps a touch less individual. (In every movement but one – see below – Hamelin’s tempi are near enough on a par with Andsnes’s, so it is largely through the cadenzas alone that he adds a little over eight minutes to Andsnes’s playing time across the disc.) In the D major Concerto, however, both pianists opt for earlier cadenzas: in Andsnes’s case, a pair composed by Haydn (although the primary source for Haydn’s cadenzas is considered less than trustworthy); in Hamelin’s case, two by Wanda Landowska, which range wider stylistically – perhaps as far as Debussy or Ravel. Richard Wigmore’s notes give no details about these Landowska cadenzas: presumably they were composed for the piano rather than the harpsichord. Whichever, they are a delightful discovery and so ear-tweaking and unusual (especially the one in the slow movement) that they alone are almost worth the price of the disc.

Hamelin and his Québécois band (the strings of Les Violons du Roy are joined by the subtle but telling presence of les hautbois et cors du roy in the D major) are recorded with a touch more presence than Andsnes and his Norwegian players, imparting a welcome earthiness to the sound – listen especially to the more muscular approach Hamelin takes in the opening movement of the G major Concerto. Other minor differences between the two discs include the use of tutti strings at the opening of the Largo cantabile of the F major (No 3), as opposed to Andsnes’s solo violin; at a rather slower tempo (7'49" against the Norwegian’s 4'59"), Hamelin here weaves an enchanting spell, approaching an almost Mozartian pathos. And where Andsnes, in the finale of the D major Concerto, holds back the tempo into the all’ungherese episode in the finale (the section referred to in official musicological circles as ‘the one that sounds like “Three Blind Mice” with trills’), Hamelin pushes forwards without dropping the tempo, heightening the delirium of this whirling gypsy dance. Add to that some unmarked col legno earlier in the same movement for an authentic touch of Hungarian paprika and the result cannot fail to raise a smile.

If one were to bring it down to the level of national stereotypes, one might say that Andsnes et al impart Haydn’s wit and wisdom with a Nordic coolness, Hamelin and friends with a Gallic shrug. Both bring different, valuable and irresistibly delicious attributes to Haydn’s music. So I’m left like a child having to choose between sweets or chocolate – and in this case, it’s hardly piggy to want both.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.