HANDEL Timotheus

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: George Frideric Handel

Genre:

Vocal

Label: Sony Classical

Magazine Review Date: 09/2013

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 103

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 88883 70481-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Timotheus oder die Gewalt der Musik |

George Frideric Handel, Composer

George Frideric Handel, Composer Gerald Finley, Bass Roberta Invernizzi, Soprano Vienna Concentus Musicus Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Singverein Werner Güra, Tenor |

Author: David Threasher

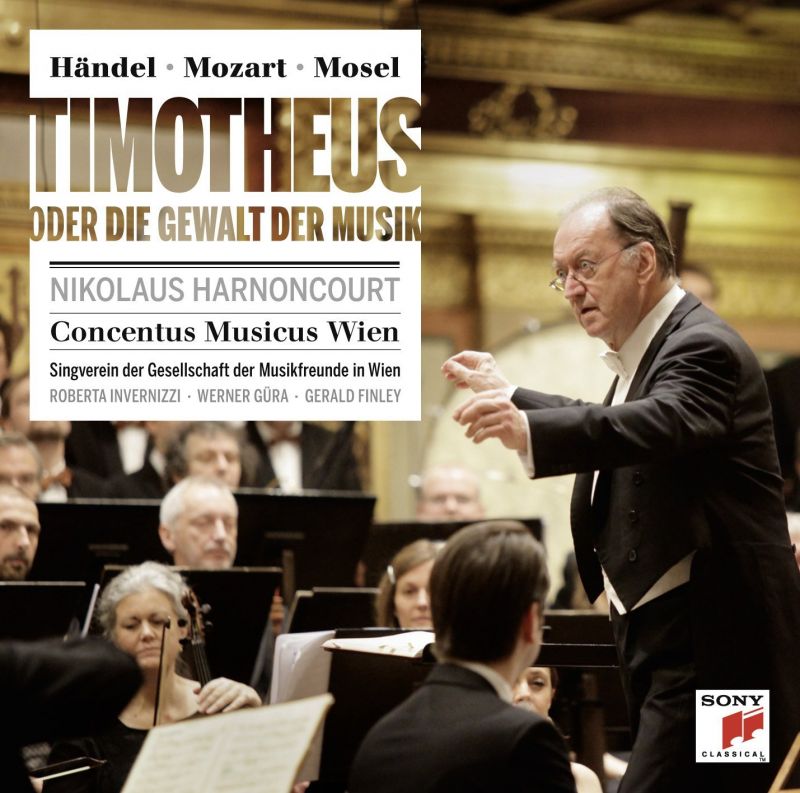

This is a recording which ticks so many worthwhile boxes that it’s difficult to know where to begin. It’s a great souvenir of a grand occasion, for sure; it’s a recording of a work that’s perhaps performed less often than a number of other similar pieces by Handel; to my knowledge, it’s the only one currently available that presents the work in Mozart’s 1790 arrangement; and it’s a score whose eventfulness plays admirably to Harnoncourt’s individual brand of theatricality.

Timotheus, though? Well, thereby hangs a tale. What we hear in terms of musical substance is to all intents and purposes Alexander’s Feast, or The Power of Musick, the pastoral ode first performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in the Lenten season of 1736. The libretto (based on Dryden) was translated into German in 1766 by CW Ramler, who saw Timotheus as the protagonist and thus adopted his name for the new libretto’s title. It was this German version that Mozart used when he updated the instrumentation for performance in Vienna in 1790 by Gottfried van Swieten’s Gesellschaft der Associierten Cavaliere; and it was Mozart’s version that was performed at the inaugural concert in 1812 of Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of the Friends of Music). This recording comes from a performance marking the bicentenary of that concert.

Why update Handel’s score? The feeling was that Handel’s instrumentation, based largely upon oboes and violins, often in unison, was too austere for the tastes of Viennese connoisseurs half a century on. And anyway, such early-18th-century techniques as clarino trumpet-playing (think of ‘The trumpet shall sound’ in Messiah) had fallen out of fashion and were no longer practised. So not only did Mozart adapt Handel’s music to the performance style of the day but he also updated the sound world, relocating the innocence of Handel’s pastoral baroquerie in the sophisticated milieu of the European Enlightenment. It was natural that Mozart’s adaptation should have been used for the 1812 performance but its conductor, Ignaz Franz von Mosel, ‘touched up’ Mozart’s score, further enriching the woodwind-writing and even adding a bass drum for added depth (and volume): watch out for it when the chorus join in the aria ‘Bacchus, ever fair and young’, and fear for your speakers! Harnoncourt prepared his performance materials for the 2012 concert from Mosel’s score and parts, still in the possession of the Gesellschaft.

Mosel had a cast of somewhere around 600700 musicians on stage, singing and playing to an audience of around 2500. Harnoncourt doesn’t muster quite so many – the booklet doesn’t enumerate but says there were ‘as many players as could be accommodated’ in the Musikverein, along with 100 chorus singers – but the right effect is achieved, the richness of Mozart’s scoring amplified by the use of wind choirs and massed brass. You hear it right from the very first note, Mozart’s characteristic woodwindwriting providing a luxurious cushion for Handel’s jagged rhythms, and again when the clarinets enter at the first chorus – a sound Handel couldn’t have imagined in 1736 but which seems so right in this context. Following the recording armed only with Handel’s score, the ear is continually delighted by a series of remarkable instrumental combinations; a particular highlight is the ghostly pairing of flute and clarinet in the soprano aria ‘He sung Darius great and good’.

There’s fun to be had, too. After an interval schnapps – and a six-minute speech by Harnoncourt in German – the trumpets and horns (and that bass drum) really go to war in the military chorus ‘Break his bands of sleep asunder’, which is rapturously received and encored, setting the scene for Gerald Finley, who hisses and sparkles with evident glee in the showstopper bass aria ‘Revenge, Timotheus cries’.

Finley is matched by the impeccable Handelian credentials of soprano Roberta Invernizzi and the ardent tenor of Werner Güra. The choir of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde revel in the choruses that are such a Handel hallmark. The audience (about the same size in 2012 as it was in 1812) only makes its presence felt when necessary. Concentus Musicus and friends convey the joy of this multicoloured score. The queasy changes of tempo in the soprano aria ‘The prince, unable to conceal his pain’ seem somewhat contrived: they’re not marked in Handel’s or Mozart’s scores but they may be Mosel’s mannerism rather than Harnoncourt’s, as too may be the inégalités in the central section of ‘Revenge, Timotheus cries’. Not that any of this can really dampen such a memorable performance. Handel loved hearing his music played with gargantuan forces and his music gave rise to a tradition of such large-scale gatherings – in Britain, at least. The ‘authentic’ movement resulted in so many anaemic, small-scale recordings that it’s a relief and a pleasure to welcome this big Timotheus, performed in such a way as Handel all too rarely is these days.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.