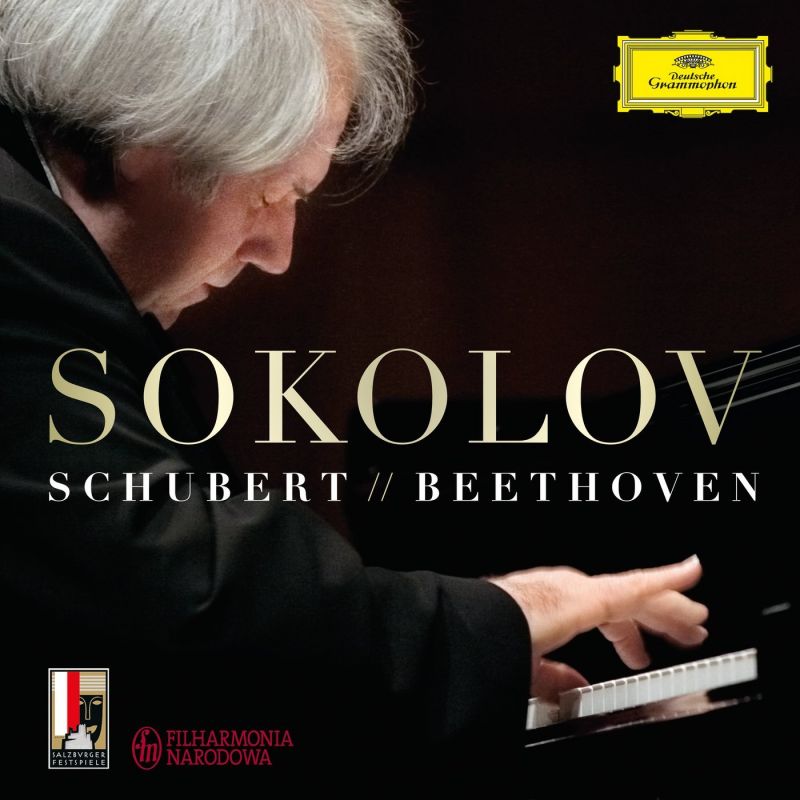

Grigory Sokolov plays Schubert & Beethoven

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Jean-Philippe Rameau, Franz Schubert, Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Magazine Review Date: 03/2016

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 138

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 479 5426GH2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| 4 Impromptus |

Franz Schubert, Composer

Franz Schubert, Composer Grigory Sokolov, Piano |

| (3) Klavierstücke |

Franz Schubert, Composer

Franz Schubert, Composer Grigory Sokolov, Piano |

| Sonata for Piano No. 29, 'Hammerklavier' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, Movement: Les tendres plaintes |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer |

| Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, Movement: Les tourbillons |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer |

| Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, Movement: Les cyclopes |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer |

| Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, Movement: La follette |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer |

| Nouvelle Suite de Pièces de Clavecin, Movement: Les sauvages |

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer |

| (3) Pieces, Movement: No. 2, Intermezzo in B flat minor |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Grigory Sokolov, Piano Johannes Brahms, Composer |

Author: David Fanning

Bafflement continues in the first of the Klavierstücke, D946, which Sokolov begins as though unaware of the notated contrasts of piano and forte. This piece feels every second of its 14 minutes, partly because – like a number of major pianists, to be sure – Sokolov includes the Andantino that Schubert (wisely, in my view) crossed out. To compensate, there is much beautiful playing in the second and third pieces.

Perhaps it’s safest to say that this is the kind of playing that divides opinion, and leave it at that. What to some may feel like hectoring rhetoric and artificial appassionato may come across to others as exhilarating freedom and compelling expressive presence. One-dimensional, mannered and predictable, or daring and inspiring…?

It is a fact, however, that at close on 53 minutes Sokolov’s Hammerklavier – from Salzburg, whereas his Schubert is from Warsaw – is exceedingly long. Probably not a world record; but those versions on my shelves clock in at anything from 37 to 48 minutes. The excess duration has nothing to do with the Scherzo, which is dispatched with a curious kind of toy-soldier peckiness but at a normal tempo, or with the fugue, which is both streamlined and superbly articulate. Rather it is down to an exceptionally grand opening movement (minim=76 or thereabouts, compared to Beethoven’s notoriously challenging 138) and a slow movement that is admittedly difficult to measure, since Sokolov’s rubato is so pervasive, but which goes by for long stretches at little more than half the notated tempo. When done with a Richterian or Yudina-esque self-negation, such things can, arguably, be made to work, and once again there is no doubting the presence of a major pianist. But with so much relentless ‘top-note’ bashing, poky pseudo-cantabile and an apparent urge to push the piano through the floor at climaxes (including an unfortunate mis-hit at the end of the first movement), I felt that my tolerance levels were being deliberately challenged, and ultimately found wanting.

Having said all that, if someone had played me Sokolov’s twinkling Rameau and dreamy Brahms encores first, I would have been champing at the bit to hear what preceded them. Go figure…

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.