GOUNOD La nonne sanglante (Equilbey)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Charles-François Gounod

Genre:

Opera

Label: Accentus

Magazine Review Date: 11/2019

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 143

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 2 110632

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (La) Nonne sanglante |

Charles-François Gounod, Composer

Accentus Ensemble Charles-François Gounod, Composer Enguerrand de Hys, Fritz; Nightwatchman, Tenor Insula Orchestra Jean Teitgen, Pierre l’Ermite, Bass Jérôme Boutillier, Comte de Luddorf, Baritone Jodie Devos, Arthur, Soprano Laurence Equilbey, Conductor Luc Bertin-Hugault, Baron de Moldaw, Bass Marion Lebègue, Agnès, la nonne sanglante, Mezzo soprano Michael Spyres, Rodolphe, Tenor Olivia Doray, Anna, Soprano Vannina Santoni, Agnès Moldaw, Soprano |

Author: Richard Lawrence

In both novel and opera the legend of the ghost of ‘The bleeding nun’ (unwisely called ‘The bloody nun’ in the subtitles here) is used as cover for Agnès and Rodolphe (Raymond in the book) to elope. But it’s the ghost who keeps the rendezvous. She subsequently haunts Rodolphe, holding him to the vows he swore when he believed her to be his Agnès. She will only lift the curse if Rodolphe avenges her death. Her murderer turns out to have been Rodolphe’s father, Luddorf, her betrothed. Thinking him dead, she had entered a convent; finding him not only alive but married she confronted him, whereupon he stabbed her to death. Rodolphe shrinks from parricide but his dilemma is resolved by Luddorf voluntarily getting himself killed in his son’s place. Lewis’s story is more complicated. The murdered nun is herself a murderess, and her demand is for her unburied bones to be deposited in the vault of the family to which both she and Raymond belong. And Agnès, far from being the virginal character of the opera, is also a nun (do keep up), pregnant by Raymond, given out as dead, but ultimately rescued from subterranean imprisonment.

Scribe and Delavigne relocated the story from Madrid under the Inquisition to 11th-century Bohemia, with Pierre the Hermit brokering peace between the Moldaw and Luddorf families by proposing a marriage between Agnès and Rodolphe’s elder brother. Gounod was happy to accept the libretto, a draft of which had been offered in turn to Berlioz, Félicien David and Verdi. It was only his second opera, given at the Paris Opéra on October 18, 1854: it ran for 11 performances before a change of management led to its being dropped. Less than five years later came Faust, probably the most popular opera of the 19th century.

The Overture begins with repeated notes on the horn, imitating the tolling of a bell; this is followed by spooky chromatic phrases. Gounod evidently knew Der Freischütz: as well as making much use of the diminished seventh chord, he copied Weber’s writing for sinister low clarinets. And the librettists gave him a Weber present, Pierre having an affinity with the Freischütz Hermit. During the Overture, the director David Bobée has the murder of the Nun by Luddorf enacted in dumb show.

Gounod and his librettists strike a good balance between the supernatural and the ordinary. There are two splendid waltzes in Act 3 (one of them displaced, with its companion Danse bohémienne, from Act 4), and light-hearted couplets for Arthur, Rodolphe’s page, who is clearly descended from Urbain, the trouser role in an earlier Scribe opera, Les Huguenots. Gounod’s inexperience shows in the Act 1 duet, where the same catchy tune is used for Rodolphe proposing elopement and Agnès begging him to go alone. But in general the drama is handled well. There’s a real frisson to the scene where Rodolphe is confronted by his ancestors; the audience in 1854 might have been reminded of another Meyerbeer opera, Robert le diable (Scribe and Delavigne again), and it’s not Gounod’s fault if we are more likely to think of the Ghosts’ High Noon in Ruddigore.

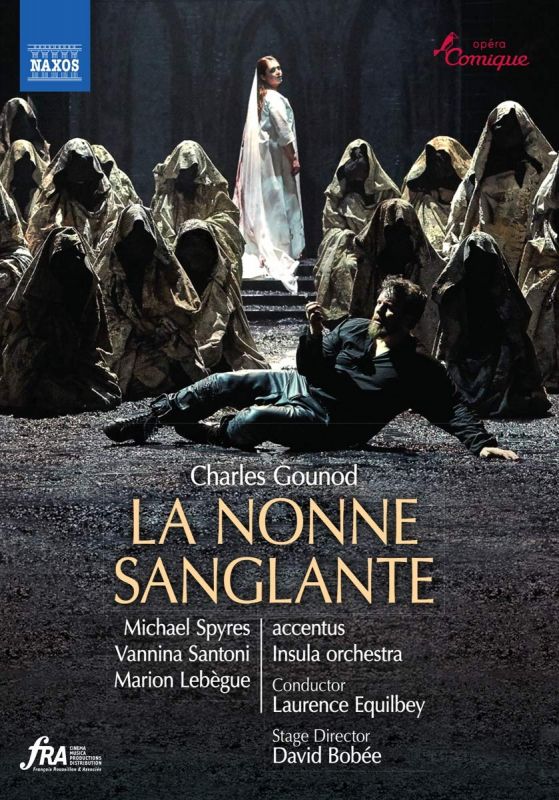

The set is plain, with video projections, and the costumes mostly monochrome. Bobée treats the drama with respect, though I do wonder why Rodolphe and Agnès are staring gloomily at the audience at the end rather than falling into each other’s arms. And when Rodolphe says that the Nun is carrying her lamp and dagger, it’s perverse for there to be a dagger but no lamp. Neither Agnès nor the Nun is given an aria but Vannina Santoni and Marion Lebègue come across strongly, especially the latter with her scary eyes. Jodie Devos makes a charming page, and Jérôme Boutillier, who learnt the part in 48 hours, is eloquent in Luddorf’s remorseful aria, ‘De mes fureurs deplorable victime’. The real weight of the action falls on the shoulders of Rodolphe. Michael Spyres is first-rate: assertive in ‘Du Seigneur, pale fiancée’, lyrical in ‘Un jour plus pur’, he sings throughout with generous, open-throated tone. And Laurence Equilbey conducts her choral and orchestral forces with passion.

There’s some carelessness in the translation of the booklet: it was Berlioz who wrote to Gounod, not vice versa, and ballet was compulsory in French opera in the 19th century, not the 20th. But do try this fine performance; then go on to read ‘Monk’ Lewis’s shocker (£8.99 from OUP or Penguin).

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.