ECCLES Semele (Perkins)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: William Wallace

Genre:

Opera

Label: AAM

Magazine Review Date: 04/2021

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 121

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: AAM012

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Semele |

John Eccles, Composer

Academy of Ancient Music Anna Dennis, Semele, Soprano Aoife Miskelly, Ino, Soprano Bethany Horak-Hallett, Cupid, Soprano Christopher Foster, Somnus, Bass Graeme Broadbent, Chief Priest, Bass Helen Charlston, Juno, Mezzo soprano Héloïse Bernard, Iris, Soprano James Rhoads, Third Priest; Second Augur, Tenor Jolyon Loy, Apollo, Baritone Jonathan Brown, Cadmus, Baritone Julian Perkins, Conductor Richard Burkhard, Jupiter, Baritone Rory Carver, Second Priest; First Augur, Tenor William Wallace, Composer |

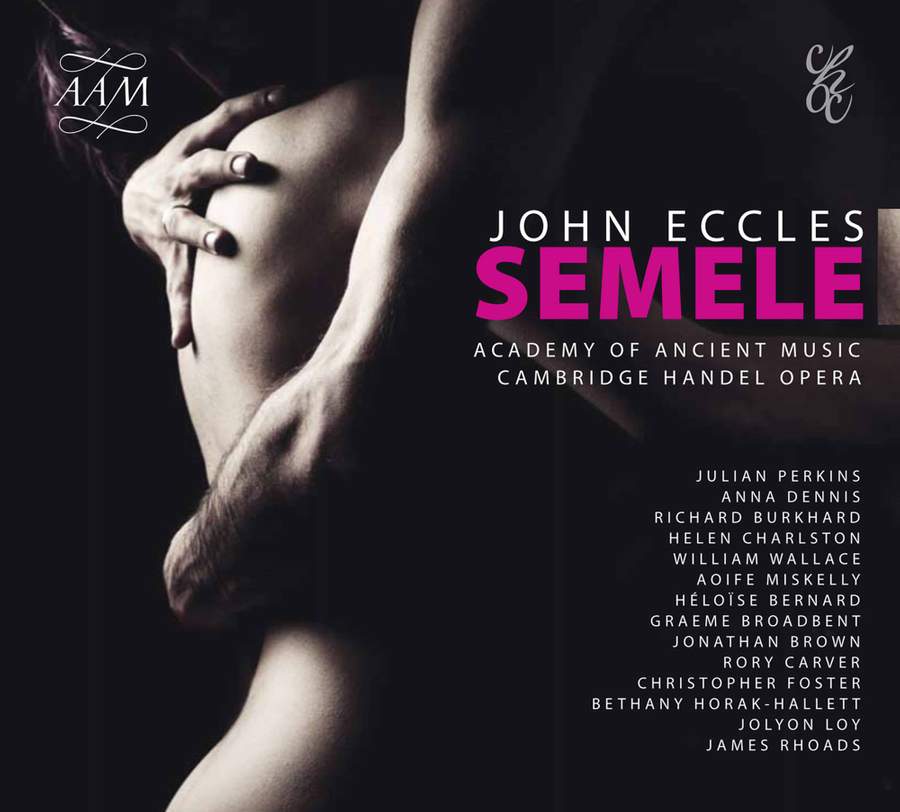

Author: Richard Wigmore

John Eccles’s setting of his friend William Congreve’s wry morality tale was one of the great might-have-beens in English operatic history. Composed around 1706 07 for the Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket, Semele was intended to capitalise on the recent fashion for all-sung English opera and the popularity of the delightfully named singing actress Anne Bracegirdle. Yet various factors, including Congreve’s acrimonious departure from the theatre and the growing taste for Italian opera, meant that it never saw the stage. After the triumph of Handel’s Rinaldo at the Queen’s Theatre in 1711, Semele did not stand a chance. Disillusioned, Eccles retired to a Thameside retreat near Kingston to indulge in his new passion for fishing. His final opera remained unperformed, apparently forgotten, until a semi-staging in the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, in 1964.

Baroque opera lovers will inevitably hear Eccles’s Semele against the background of Handel’s now-famous work – an opera thinly disguised as an oratorio. There are no obvious plums to compete with ‘Endless pleasure’ or ‘Where’er you walk’. But comparisons are unfair. Eccles was a consummate theatrical professional, with an acute dramatic sense. The plot surges forwards in a flexible sequence of recitative, arioso and short arias, plus a handful of ensembles (no chorus). Eccles’s overall tone is more intimate, more inward than Handel’s, with preening virtuosity at a minimum. Each of the characters, blinded by love, revenge or ambition, comes alive in music whose idiom might be described as Italianised English, with the occasional nod to French tragédie lyrique. Echoes of Purcell, albeit without Purcellian cross-rhythms and spicy harmonic clashes, mingle with more flamboyant – and to our ears Handelian – arias in the modish Italian style.

With the only previous recording of Semele, directed by Anthony Rooley (Forum, A/04), now unavailable, this new version has the field to itself. It will be a hard act, in both performance and presentation, for any competitor to follow. ‘This opera oozes drama’, writes Julian Perkins in his note, and goes on to prove his point. Pacing, not least in the expressive recitatives, is fluid and natural, the playing of the AAM strings tingles with theatrical life and the young cast is uniformly fine.

As Semele – a more fragile, vulnerable figure than her Handelian equivalent – Anna Dennis combines purity with a touch of sensuous richness. Hers is a lovely piece of singing and characterisation. Semele’s implacable rival Juno should steal the show whenever she appears. From her imperious opening entry to her rollicking final aria of triumph, her tone dripping with venomous glee, Helen Charlston does not miss a trick. Richard Burkhard’s Jupiter, assigned the opera’s most Italianate music, sounds slightly inhibited reassuring Semele in his first aria but quickly grows in ardour. Aoife Miskelly brings a warm, flavoursome mezzo to the role of Semele’s sister Ino. Her singing of the plangent ‘Turn, hopeless lover’, strings sighing in sympathy with the voice, is a highlight. Among the minor roles, William Wallace deftly negotiates the high tessitura of Athamas’s music, while Héloïse Bernard (Iris) and Bethany Horak-Hallett (Cupid) sing their appealing Purcellian solos with grace and guile.

The discs, superb as they are, are far from the whole story. Anyone who has acquired the AAM’s recording of Handel’s Brockes Passion (11/19) will know that their classy documentation is an education in itself. What we get is a lavishly illustrated 200-page book, with lively articles on Eccles’s career, the London theatrical scene c1700, Italian influences on English violin-playing (a brilliant essay from Judy Tarling), and the mythological background. Did you know, incidentally, that Semele was the great-great aunt of Oedipus? I certainly didn’t!

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.