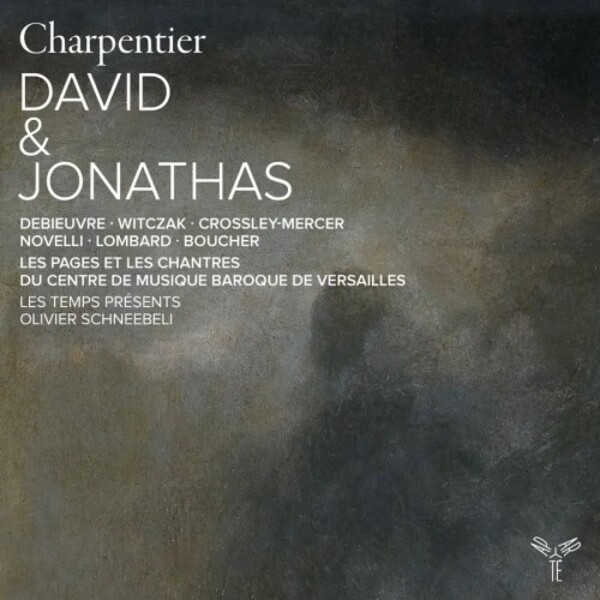

CHARPENTIER David et Jonathas (Schneebeli)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Opera

Label: Aparte

Magazine Review Date: 06/2024

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 122

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: AP342

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| David et Jonathas |

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Composer

(Les) Pages du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles Clément Debieuvre, David, Tenor David Witczak, Saül, Bass Edwin Crossley-Mercer, Achis; Ghost of Samuel, Bass Jean-François Lombard, La Pythonisse, Tenor Jean-Francois Novelli, Joabel; Captive, Tenor Natacha Boucher, Jonathas, Soprano Olivier Schneebeli, Conductor Orchestre Les Temps Présents |

Author: David Vickers

Having rejoiced in March at the first top-class interpretation of David et Jonathas to emerge in donkey’s years, just a short while later here comes another fresh perspective. This is Olivier Schneebeli’s swansong upon his retirement after 30 years of service as conductor of the combined choir of children and adult students at the Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles. Indeed, all of the soloists featured here are current or former members of the CMBV choir. As it happens, this was recorded at Versailles in conjunction with a concert at the Opéra Royal more than a year before Gaétan Jarry’s marvellous performance (fully staged, paradoxically, in the chapel).

Schneebeli explains his aim for David et Jonathas to be ‘seen insofar as possible in the light of its creation’. Charpentier and librettist Pierre Chamillart devised it as a prologue and intermède alternating with the five spoken acts of François Bretonneau’s Latin play Saül, acted by schoolboys at Paris’s Jesuit Collège Louis-le-Grand in February 1688. Accordingly, Schneebeli eschews adult female singers, and the choir and cast are entirely men and children; Jonathan is sung by the girl Natacha Boucher and four boy trebles take assorted small solo roles. To compensate for the long-lost Bretonneau play, seven acting narrators drawn from the choir recite ‘declamations’ selected from Antoine Godeau’s Paraphrase de la plainte de David sur la mort de Saül & de Jonathas (1633). These brief speeches create a distant impression of the original context of Charpentier’s music, although the last declamation is an inopportune disturbance that splits apart David’s sorrows upon the death of Jonathan in Act 5 scene 4.

The prologue’s overture springs to life vividly and is overlaid with portentous sound effects. Saul’s monologue as he is about to resort desperately to outlawed witchcraft is performed sympathetically by David Witczak (the only cast member who takes the same role for Jarry). Jean-François Lombard’s Pythoness has suitable ombra unnaturalness when conjuring the ghost of Samuel – whose prophecy of the impious king’s doom is delivered ominously by Edwin Crossley-Mercer, accompanied by pungent bassoons and violas da gamba. There is immediately a sharp contrast of atmosphere in Act 1’s celebratory trumpet march, and then assorted warriors, shepherds and liberated captives praise David’s heroic exploits in a divertissement that flows with lilting dancelike momentum; a lovely pastoral ariette is sung smoothly by boy treble Evan Bidaut (joined by recorders), and a syncopated song is performed animatedly by baritone Thierry Cartier and the boys’ choir.

Clément Debieuvre’s soft high tenor conveys the pathos of David’s assorted laments with elegant intimacy; there is also rhythmical assertion in his duet with Crossley-Mercer’s extrovert Achis (Act 1 scene 4). Jean-François Novelli applies theatrical spitefulness to the envious Joabel’s quarrel with the disinterested hero (Act 2 scene 2). The extended sequence of duets, solos and choruses at the close of Act 2 is performed as a cheerful dance rather than conveying the seductive blissfulness that the chaconne might offer. Witczak understates Saul’s paranoia in his Act 3 soliloquy, but, if anything, casting the young Boucher as Jonathan increases our impressions of the father’s cruelty and the son’s vulnerability during their strained conversation. Boucher’s singing has laudable maturity of sentimental power in Jonathan’s hopelessness on the cusp of the fatal battle (Act 4 scene 3) and his dying farewell to an insane Saul (Act 5 scene 2). There is clarity and responsive flexibility throughout proceedings from Les Temps Présents, whose instrumentalists participate fully in Charpentier’s integrated dramatisations.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.