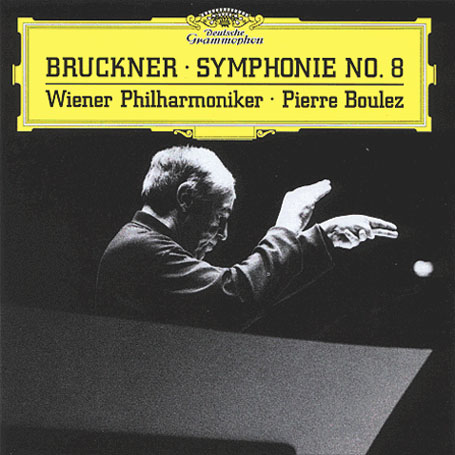

Bruckner Symphony No. 8

Boulez’s interpretative strengths are much in evidence here: form and texture are clearly articulated, the drama finely unfolded

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Anton Bruckner

Label: DG

Magazine Review Date: /2000

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 76

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 459 678-2GH

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 8 |

Anton Bruckner, Composer

Anton Bruckner, Composer Pierre Boulez, Conductor Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra |

Author: Richard Osborne

‘From the very outset, I accepted that I would undoubtedly get more from the orchestra than they would get from me.’ Thus Pierre Boulez, composer, conductor and diplomat manque, recalling the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s invitation to him to conduct Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony in the Bruckner church at St Florian in 1996. After hearing this new recording, ‘Up to a point, Lord Copper’ is the response I think | I would be most inclined to give to this modest disclaimer.

It is true that if you are planning to climb Everest only the best Sherpas will do, and where Bruckner’s Eighth is concerned the Vienna Philharmonic is the nonpareil. The work lies deep in the orchestra’s collective unconscious. It played the premiere under Hans Richter in December 1892 and, thanks to a more or less unbroken tradition of playing the work under master Brucknerians, it knows it today as well as it has ever done. But how does it know it? In the dark days of the autumn of 1944, Furtwangler directed the orchestra in the most Manichean of all recorded Eighths, tragic and actual. But they were unusual times and that is an unusual view. The most revered recent Viennese recordings – Giulini’s lyric epic or the stoic late Karajan – appear to place the symphony in the context, not of time but of eternity. Not so Boulez. His Bruckner, like his Wagner – his Bayreuth Ring (Philips, 10/92) and his 1970 Bayreuth Parsifal (Philips, 9/92) – has the sting of actuality about it.

Wagner is the key here. As Boulez has observed, it is odd how French composers and conductors steadfastly ignored Bruckner’s music whilst at the same time being obsessively interested in Wagner. Though Boulez himself is famously impatient with Wagner’s texts (‘the music purifies the bric-a-brac of the words’), he has always shown a special interest in Parsifal where music and musical forms are at their least illustrative, their most self-sufficient. From there it is a comparatively short step to late Bruckner. The only surprise is how long it has taken Boulez to take that step.

Though there were those who found his Bayreuth Parsifal restless and rootless, there was no denying the performance’s sonic translucence. A quarter of a century on, the translucence remains. The Vienna Philharmonic string- sound here is taut, tense, live, lit from within, the playing in the slow movement especially memorable. But the shape is there, too. This St Florian performance moves persistently forward yet is restful and rooted in a way that few ‘urgent’ Eighths are: Jochum’s, for example, with its absurd sudden accelerations (DG, 2/90) or Solti’s (Decca, 10/92), glib and rhythmically unstable in the longer term.

Boulez’s reading of the first movement is not especially remarkable. Eloquent as the Vienna Philharmonic playing is, the very objectivity of the approach drains the final climax and coda of tragic menace. The Scherzo is persuasive, though controversially fleet, no Allegro moderato, a kind of Austrian ‘Fetes’. It is in the slow movement and finale that greatness comes. In most performances, the finale is poorly known and poorly ordered; in the early days of Bruckner recording only Karajan seemed to have its measure. Architecturally and orchestrally, Boulez’s performance is vivid and finely marshalled.

It is no surprise to learn that he was chary of recording Bruckner in a church acoustic. DG’s recording team appears to have responded to his fears by creating what amounts to a virtual-reality St Florian. The strings have a studio-like immediacy, the winds an ambient glow which is probably as much electronic as it is ecclesiastical. Occasionally, the balance seems to be reversed, winds to the fore, the strings pulsing beneath and beyond. The bottom line is, it works for this performance. Compare this with the muddle Gunter Wand and his North German Radio engineers got into in Lubeck Cathedral in 1987 (RCA, 8/88 – nla) and it is starred alphas all round to the DG team.

Played at high levels the recording is terrifying in its power. Happily, it works well at lower levels, too. You don’t have to deafen yourself to experience the Brucknerian actuality, Boulez-style.'

It is true that if you are planning to climb Everest only the best Sherpas will do, and where Bruckner’s Eighth is concerned the Vienna Philharmonic is the nonpareil. The work lies deep in the orchestra’s collective unconscious. It played the premiere under Hans Richter in December 1892 and, thanks to a more or less unbroken tradition of playing the work under master Brucknerians, it knows it today as well as it has ever done. But how does it know it? In the dark days of the autumn of 1944, Furtwangler directed the orchestra in the most Manichean of all recorded Eighths, tragic and actual. But they were unusual times and that is an unusual view. The most revered recent Viennese recordings – Giulini’s lyric epic or the stoic late Karajan – appear to place the symphony in the context, not of time but of eternity. Not so Boulez. His Bruckner, like his Wagner – his Bayreuth Ring (Philips, 10/92) and his 1970 Bayreuth Parsifal (Philips, 9/92) – has the sting of actuality about it.

Wagner is the key here. As Boulez has observed, it is odd how French composers and conductors steadfastly ignored Bruckner’s music whilst at the same time being obsessively interested in Wagner. Though Boulez himself is famously impatient with Wagner’s texts (‘the music purifies the bric-a-brac of the words’), he has always shown a special interest in Parsifal where music and musical forms are at their least illustrative, their most self-sufficient. From there it is a comparatively short step to late Bruckner. The only surprise is how long it has taken Boulez to take that step.

Though there were those who found his Bayreuth Parsifal restless and rootless, there was no denying the performance’s sonic translucence. A quarter of a century on, the translucence remains. The Vienna Philharmonic string- sound here is taut, tense, live, lit from within, the playing in the slow movement especially memorable. But the shape is there, too. This St Florian performance moves persistently forward yet is restful and rooted in a way that few ‘urgent’ Eighths are: Jochum’s, for example, with its absurd sudden accelerations (DG, 2/90) or Solti’s (Decca, 10/92), glib and rhythmically unstable in the longer term.

Boulez’s reading of the first movement is not especially remarkable. Eloquent as the Vienna Philharmonic playing is, the very objectivity of the approach drains the final climax and coda of tragic menace. The Scherzo is persuasive, though controversially fleet, no Allegro moderato, a kind of Austrian ‘Fetes’. It is in the slow movement and finale that greatness comes. In most performances, the finale is poorly known and poorly ordered; in the early days of Bruckner recording only Karajan seemed to have its measure. Architecturally and orchestrally, Boulez’s performance is vivid and finely marshalled.

It is no surprise to learn that he was chary of recording Bruckner in a church acoustic. DG’s recording team appears to have responded to his fears by creating what amounts to a virtual-reality St Florian. The strings have a studio-like immediacy, the winds an ambient glow which is probably as much electronic as it is ecclesiastical. Occasionally, the balance seems to be reversed, winds to the fore, the strings pulsing beneath and beyond. The bottom line is, it works for this performance. Compare this with the muddle Gunter Wand and his North German Radio engineers got into in Lubeck Cathedral in 1987 (RCA, 8/88 – nla) and it is starred alphas all round to the DG team.

Played at high levels the recording is terrifying in its power. Happily, it works well at lower levels, too. You don’t have to deafen yourself to experience the Brucknerian actuality, Boulez-style.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.