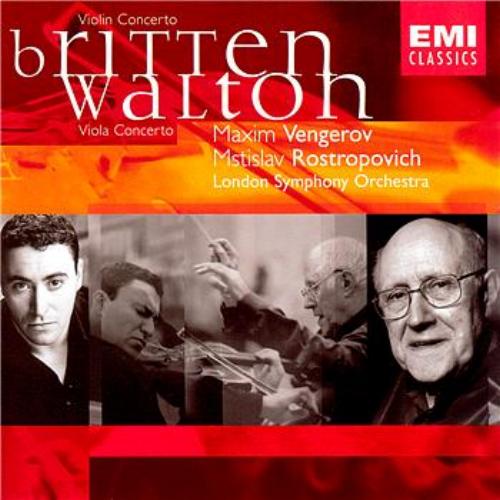

Britten Violin Concerto; Walton Viola Concerto

Gripping, if hardly conventional, readings of two major English string concertos

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: William Walton, Benjamin Britten

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: EMI Classics

Magazine Review Date: 7/2003

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 64

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: 557510-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Violin and Orchestra |

Benjamin Britten, Composer

Benjamin Britten, Composer London Symphony Orchestra Maxim Vengerov, Violin Mstislav Rostropovich, Conductor |

| Concerto for Viola and Orchestra |

William Walton, Composer

London Symphony Orchestra Maxim Vengerov, Violin Mstislav Rostropovich, Conductor William Walton, Composer |

Author: Edward Greenfield

When artists of the stature of Vengerov and Rostropovich tackle English music it is often a revelation, and here you have some of the most ravishing string-playing I have ever heard in either of these masterpieces. This is music-making as a love affair. That said, these readings do not always follow convention, let alone metronome markings, and there is at least one choice of tempo which I can imagine will have traditionalists spluttering in protest. Yet even there the gains and insights demand that these performances should be heard by the widest audience, not just devotees of Britten and Walton. The greatness of both works is reinforced.

As one might expect with Rostropovich as conductor, the Britten is the less controversial of the two readings. The soloist’s first entry over crisply sprung ostinato repetitions on bassoon and harp is marked dolcissimo, and the sweetness of Vengerov’s playing in the high-lying cantilena is nothing short of heavenly. Here and throughout the work the soloist’s free expressiveness, his use of rubato, far from sounding forced, reflects a seemingly spontaneous understanding, the creative insight of a major artist, rapt and intense. Rostropovich and the LSO match him in their warm expressiveness, so that when on the reprise of that first subject the roles are reversed, the orchestral violins are just as sweet and tender in the melody, while Vengerov points the nagging rhythm of the ostinato with a delectable spring, far more delicate than Mark Lubotsky on the recording with Britten himself conducting.

Vengerov’s resilience in the ‘dance of death’ rhythms of the central Scherzo is just as winning. Where Lydia Mordkovitch on the Chandos version conveys a Russian wildness in her similarly brilliant performance, Vengerov conveys exuberance, the fun behind this demonic music when a virtuoso so completely masters a challenge. The long Passacaglia finale finds Vengerov and Rostropovich both so concentrated that each succeeding section builds up with unstoppable momentum. Vengerov’s first entry reflects the marking inquieto more hauntingly than I have ever known, while the long epilogue ends on a breathtaking pianissimo. Here and throughout, the full-blooded recording not only covers the widest dynamic range, but brings out many inner details in the orchestral writing normally obscured.

That is also true of the Russians’ reading of the Walton Viola Concerto, with Vengerov evidently just as much at ease on the larger instrument as on his violin. Yet the timings alone will bear witness to the individuality of the reading. Ever since Menuhin recorded the work with the composer conducting, I have regularly suggested that the lyrical first movement, Andante comodo, should not be taken too slowly, remembering the early recordings of Frederick Riddle and William Primrose (both with Walton conducting). If I say that Vengerov is even more expansive than Kennedy or Bashmet on the versions I have listed, the wonder is that, with Rostropovich in total sympathy, he sustains the slow tempo with rapt intensity, pure and tender with no hint of soupiness of the kind that mars the Kennedy version. The beauty of the movement is even intensified. In the central Scherzo Vengerov with lifted rhythms, as in the Britten, brings out the fun, jazzing the syncopations seductively, but the really controversial speed is left to the Allegro moderato finale, which takes an astonishing 16'23", or three-and-a-half minutes longer than even the expansive Bashmet, and six minutes longer than Riddle.

Yet with the jaunty opening theme on bassoon so deliciously pointed, sounding like a cakewalk from Facade, this is a new revelation which may defy convention to the point of perversity but which proves magnetic from first to last, thanks to the concentration of soloist and conductor. Here, again, Vengerov’s ethereal playing above the stave brings many moments of total magic. Unconventional as it is, this is a reading that demands to be heard, even if Waltonians will hardly want it as their only choice. For a modern reading that comes nearer than any to the original approach sanctioned by the composer, my own choice is Paul Neubauer with Andrew Litton and the Bournemouth orchestra, but for a unique experience don’t miss the new disc.

As one might expect with Rostropovich as conductor, the Britten is the less controversial of the two readings. The soloist’s first entry over crisply sprung ostinato repetitions on bassoon and harp is marked dolcissimo, and the sweetness of Vengerov’s playing in the high-lying cantilena is nothing short of heavenly. Here and throughout the work the soloist’s free expressiveness, his use of rubato, far from sounding forced, reflects a seemingly spontaneous understanding, the creative insight of a major artist, rapt and intense. Rostropovich and the LSO match him in their warm expressiveness, so that when on the reprise of that first subject the roles are reversed, the orchestral violins are just as sweet and tender in the melody, while Vengerov points the nagging rhythm of the ostinato with a delectable spring, far more delicate than Mark Lubotsky on the recording with Britten himself conducting.

Vengerov’s resilience in the ‘dance of death’ rhythms of the central Scherzo is just as winning. Where Lydia Mordkovitch on the Chandos version conveys a Russian wildness in her similarly brilliant performance, Vengerov conveys exuberance, the fun behind this demonic music when a virtuoso so completely masters a challenge. The long Passacaglia finale finds Vengerov and Rostropovich both so concentrated that each succeeding section builds up with unstoppable momentum. Vengerov’s first entry reflects the marking inquieto more hauntingly than I have ever known, while the long epilogue ends on a breathtaking pianissimo. Here and throughout, the full-blooded recording not only covers the widest dynamic range, but brings out many inner details in the orchestral writing normally obscured.

That is also true of the Russians’ reading of the Walton Viola Concerto, with Vengerov evidently just as much at ease on the larger instrument as on his violin. Yet the timings alone will bear witness to the individuality of the reading. Ever since Menuhin recorded the work with the composer conducting, I have regularly suggested that the lyrical first movement, Andante comodo, should not be taken too slowly, remembering the early recordings of Frederick Riddle and William Primrose (both with Walton conducting). If I say that Vengerov is even more expansive than Kennedy or Bashmet on the versions I have listed, the wonder is that, with Rostropovich in total sympathy, he sustains the slow tempo with rapt intensity, pure and tender with no hint of soupiness of the kind that mars the Kennedy version. The beauty of the movement is even intensified. In the central Scherzo Vengerov with lifted rhythms, as in the Britten, brings out the fun, jazzing the syncopations seductively, but the really controversial speed is left to the Allegro moderato finale, which takes an astonishing 16'23", or three-and-a-half minutes longer than even the expansive Bashmet, and six minutes longer than Riddle.

Yet with the jaunty opening theme on bassoon so deliciously pointed, sounding like a cakewalk from Facade, this is a new revelation which may defy convention to the point of perversity but which proves magnetic from first to last, thanks to the concentration of soloist and conductor. Here, again, Vengerov’s ethereal playing above the stave brings many moments of total magic. Unconventional as it is, this is a reading that demands to be heard, even if Waltonians will hardly want it as their only choice. For a modern reading that comes nearer than any to the original approach sanctioned by the composer, my own choice is Paul Neubauer with Andrew Litton and the Bournemouth orchestra, but for a unique experience don’t miss the new disc.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.