Britten (The) Turn of the Screw

Memorable conducting and singing make this the best modern version of a classic chamber opera

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Benjamin Britten

Genre:

Opera

Label: Virgin Classics

Magazine Review Date: 10/2002

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 106

Mastering:

Stereo

DDD

Catalogue Number: 545521-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (The) Turn of the Screw |

Benjamin Britten, Composer

Benjamin Britten, Composer Caroline Wise, Flora, Soprano Daniel Harding, Conductor Ian Bostridge, Prologue, Tenor Ian Bostridge, Peter Quint, Tenor Jane Henschel, Mrs Grose, Soprano Joan Rodgers, Governess, Soprano Julian Leang, Miles, Treble/boy soprano Mahler Chamber Orchestra Vivien Tierney, Miss Jessel, Soprano |

Author: Alan Blyth

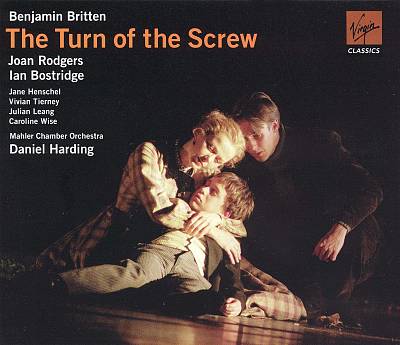

This absorbing version of Britten’s arresting masterpiece (derived from Henry James’s ever-mysterious short story) is based on the stage performances given by London’s Royal Opera in Deborah Warner’s controversial staging. It offers a considerable challenge to both the première recording, conducted by the composer, and the more recent version conducted by Steuart Bedford, originally released by Collins Classics (6/94) but alas currently unavailable. As with these, the new recording catches all the sinister fascination of Britten’s most tautly composed opera score, so aptly matched to James’s tale and to Myfanwy Piper’s evocative libretto.

Daniel Harding is a worthy successor of and rival to the composer and to Steuart Bedford in extracting the greatest tension from both the finely wrought writing for the chamber ensemble and from his well-balanced and, by and large, exemplary cast. He is helped by the clearest and most detailed recording the work has yet received. The old mono set has the advantage of catching even more of the claustrophobic nature of the piece, but it cannot, of course, equal the new one in presence or range. The Bedford set suffers a little from a slightly too backward placing of the singers, but it is as finely executed as the new one and boasts David Owen Norris’s virtuoso account of the piano variation.

When discussing the merits of the casts one is comparing three teams of undoubted excellence. Nevertheless there are distinctions to be made. As on stage, Joan Rodgers nicely balances the need to suggest the ingenuous and the excitable side of the Governess’s nature, which she conveys in a performance that combines clarity of diction with the vocal verities. Which is not to say she surpasses Felicity Lott’s wholly convincing portrayal for Bedford, let alone the perfectly sung and anguish-filled reading of Jennifer Vyvyan, the role’s creator, for Britten.Bostridge’s ethereal, other-worldly, eerily magnetic Quint provides an interesting contrast with Philip Langridge’s more forceful and present assumption for Bedford. I now prefer both to Pears’s more mannered singing on the pioneering set, but that, needless to say, has its own authority. On the other hand neither Vivian Tierney nor Nadine Secunde (Bedford) quite match the searing sadness of Arda Mandikian’s dark-hued Miss Jessel for Britten. In the case of Mrs Grose, Jane Henschel, imposingly as she sings, sounds a trifle too stock-operatic in her responses to words and notes beside the particular gentility of Joan Cross (Britten) or – even better – the marvellously detailed and intensely uttered interpretation of Phyllis Cannan (Bedford).

Warner chose to have a girl of the right age to play and sing Flora, which worked well on stage. On disc, the voice heard here is simply too slight to cope with Britten’s writing. Olive Dyer in the original cast manages to sound convincingly girlish while encompassing the notes more strongly. Julian Leang manages to catch Miles’s seemingly equivocal nature, though not quite as well as David Hemmings for Britten. Bedford’s boy is weak.

Before I made my comparisons, I must say that I was utterly absorbed by the new version and, given its masterly engineering and sense of atmosphere would, by a hair’s-breadth, prefer it to the Bedford among stereo recordings (and I have not forgotten the various merits of Sir Colin Davis’s version on Philips). The composer’s set remains both a historic document and – still – the most taut reading, but most will prefer and be satisfied with the conviction and the sound of this newcomer.

Daniel Harding is a worthy successor of and rival to the composer and to Steuart Bedford in extracting the greatest tension from both the finely wrought writing for the chamber ensemble and from his well-balanced and, by and large, exemplary cast. He is helped by the clearest and most detailed recording the work has yet received. The old mono set has the advantage of catching even more of the claustrophobic nature of the piece, but it cannot, of course, equal the new one in presence or range. The Bedford set suffers a little from a slightly too backward placing of the singers, but it is as finely executed as the new one and boasts David Owen Norris’s virtuoso account of the piano variation.

When discussing the merits of the casts one is comparing three teams of undoubted excellence. Nevertheless there are distinctions to be made. As on stage, Joan Rodgers nicely balances the need to suggest the ingenuous and the excitable side of the Governess’s nature, which she conveys in a performance that combines clarity of diction with the vocal verities. Which is not to say she surpasses Felicity Lott’s wholly convincing portrayal for Bedford, let alone the perfectly sung and anguish-filled reading of Jennifer Vyvyan, the role’s creator, for Britten.

Warner chose to have a girl of the right age to play and sing Flora, which worked well on stage. On disc, the voice heard here is simply too slight to cope with Britten’s writing. Olive Dyer in the original cast manages to sound convincingly girlish while encompassing the notes more strongly. Julian Leang manages to catch Miles’s seemingly equivocal nature, though not quite as well as David Hemmings for Britten. Bedford’s boy is weak.

Before I made my comparisons, I must say that I was utterly absorbed by the new version and, given its masterly engineering and sense of atmosphere would, by a hair’s-breadth, prefer it to the Bedford among stereo recordings (and I have not forgotten the various merits of Sir Colin Davis’s version on Philips). The composer’s set remains both a historic document and – still – the most taut reading, but most will prefer and be satisfied with the conviction and the sound of this newcomer.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.