BRAHMS The Final Piano Pieces (Stephen Hough)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Johannes Brahms, Stephen Hough

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Hyperion

Magazine Review Date: 01/2020

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 69

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: CDA68116

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (7) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Stephen Hough, Composer |

| (3) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Stephen Hough, Composer |

| (6) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Stephen Hough, Composer |

| (4) Pieces |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Stephen Hough, Composer |

Author: Michelle Assay

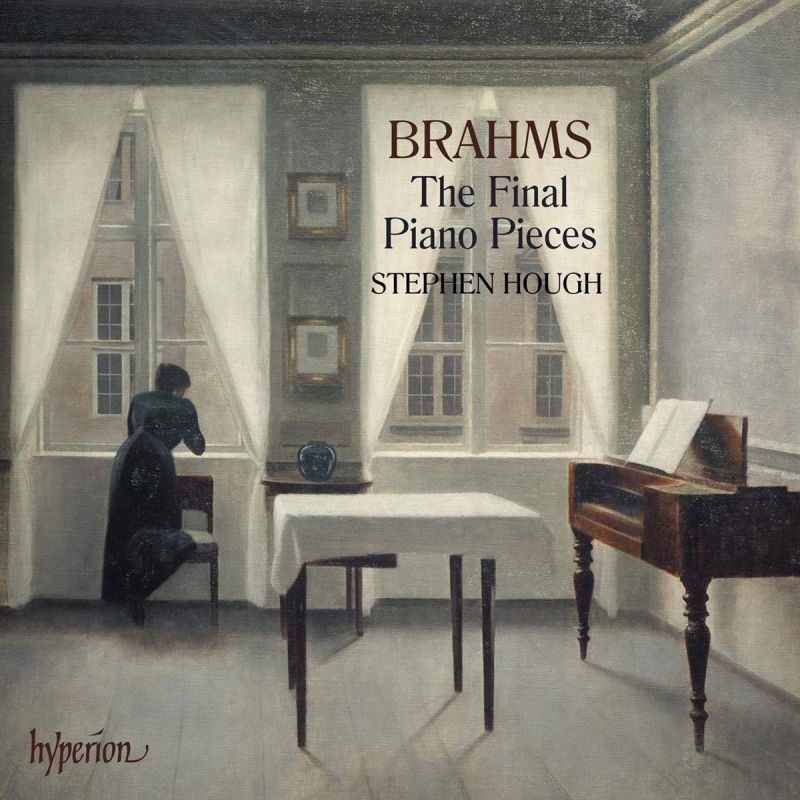

Blend imaginative yet learned interpretation, profound sensitivity and poetry, and personal charisma, and you have here one of the finest accounts of Brahms’s late piano works on record, one that stands head and shoulders above most contenders in an ever-growing catalogue. I always revel in the prospect of a new disc by Stephen Hough. The superlative piano-playing aside, the whole presentation is so thoughtful: the choice of cover illustration, the imaginative programming (remember his Janáček and Scriabin pairing) and his essays or booklet contributions. In this case the booklet notes are largely a reprint of Misha Donat’s text for Hyperion’s previous recording with Garrick Ohlsson but they are crowned by a short yet highly charged note from Hough. And the quietly evocative atmosphere of Vilhelm Hammershøi’s painting on the cover sets the scene for what is inside. So much to enjoy, even before hearing a note.

The picture and Hough’s words are key to understanding his approach to these so often played works, though admittedly his ravishing colouristic palette has no analogy in the shades of grey of Hammershøi’s masterpiece. In much more eloquent words than mine, Hough comments on late style in general and how Brahms fits, or rather refuses to fit, with the clichés of mortality and decay, of a return to simplicity, transparency of texture and so on. Brahms transcends all these. His are intimate, even lonely creations, with autumnal but multicoloured emotional shades, ranging from the stirring outbursts of the three Capriccios of Op 116 to perhaps the closest music has come to depicting sunset, in the first Intermezzo of Op 119. Hough is supremely sensitive to the passage of time between these two opuses. What a journey he takes us on from the stormy, surging quality of much of Op 116, to the nostalgia that predominates in Op 119; it’s as if the shadow of Schumann is gradually effaced as we travel between these works.

Hough reveals each miniature as a compact piece of theatre, putting an array of timbres and varied accentuation at its service. For him late Brahms is evidently not so much Prospero hanging up his magic garments as a compilation of many characters and soliloquys, and certainly much more than ‘lullabies of his grief’. I wonder if Brahms would have regretted those words about his Op 117 Intermezzos (if indeed he ever actually said them) had he heard the self-indulgent sentimentality that bedevils so many modern recordings. Hough takes his cue rather from the often ignored moderato and con moto that qualify the Andante markings in the first and third of this set. As well-intentioned as some of the more conventional rival readings may be – Plowright (too plodding), Ohlsson (remarkably flat and two-dimensional) and even, dare I say, Volodos – Hough’s noble and cleansing version (closer to the tempos of Kempff in 1963 than anyone else) makes it hard to go back to hearing these pieces that way.

Take the final Intermezzo of Op 118, for instance. How persuasively it grows out of the resignation of the preceding F major Romance, via its own solitary opening gesture, into a full-blown tragedy, culminating in an earth-shattering outcry of protest. Remembering this as the last piece I ever heard my own teacher play before her death, I have cried to many interpretations; but for me none has reached the profundity of Hough’s. Naturalness, nobility and simplicity in the face of apparent complexity are his main weapons. Compared to him, Volodos, for all the equal mastery of his pianism, feels theatrical and impersonal. You feel you are somehow sitting beside Hough’s Brahms at the piano, being taken right inside the music; whereas Volodos is on a big stage where you can only marvel from afar.

The steely brightness of Hough’s Yamaha in the more explosive numbers may raise some eyebrows. But hear how he turns it to his advantage in the G minor Ballade of Op 118, for instance, to create a three-dimensional soundscape. And hear how subtly his pedalling works with the acoustics of the room and the resonance of the instrument to make the richest of textures as lean and suggestively meaningful as Hammershøi’s painting. In his natural, unmannered freedom, Hough can be ranged alongside Radu Lupu (though the 1982 Decca recording quality cannot compare). Both join hands with the treasurable few Brahms recordings that have survived from Ilona Eibenschütz, friend of the composer who gave the private premieres of Op 118 and Op 119.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.