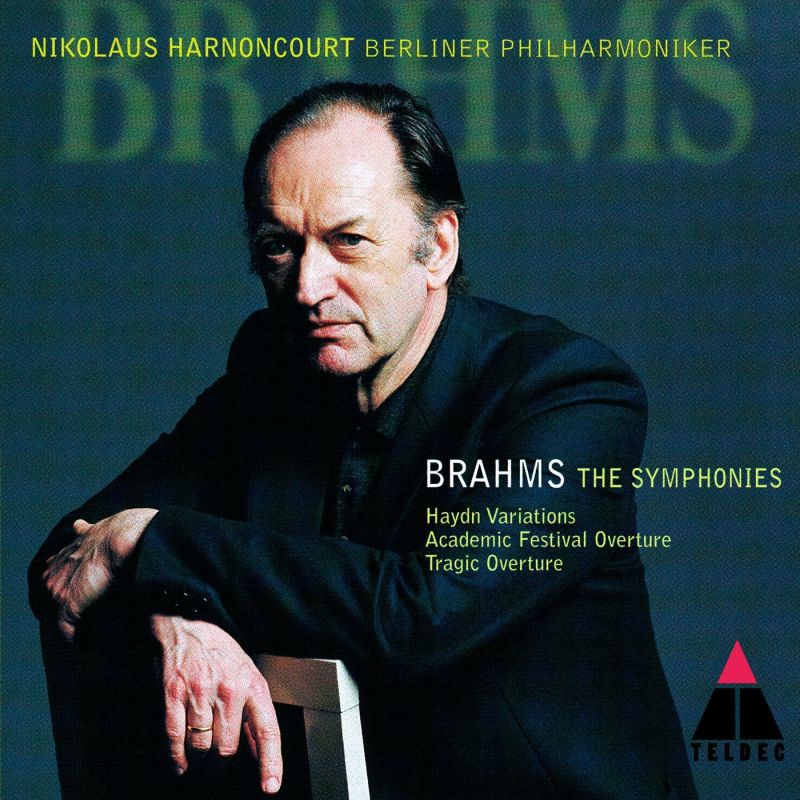

Brahms Symphonies Nos 1-4; Overtures etc

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Johannes Brahms

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Teldec (Warner Classics)

Magazine Review Date: 11/1997

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 214

Catalogue Number: 0630-13136-2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 1 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 2 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 3 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 4 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Variations on a Theme by Haydn, 'St Antoni Chorale |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Academic Festival Overture |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

| Tragic Overture |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johannes Brahms, Composer Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Conductor |

Author:

First, let me dispel any fears that Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s Brahms is quirky, provocative or abrasive. Yes, there are interpretative novelties (freshly considered articulation and clarified counterpoint) and, yes, it is true that the Berlin strings project a smooth, curvaceous profile that is quite unlike, say, Abbado’s leanness, Furtwangler’s lunging sonorities or the solid mass of tone habitually favoured by Karajan. As with Sir Charles Mackerras’s recent Telarc cycle with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Harnoncourt makes a beeline for the brass, and the horns in particular, though their freshly-won prominence is due more, I suspect, to fastidious internal balancing and specific instruments used than to any over-zealousness on the part of the players. The live recordings have remarkable presence and are mostly cough-free.

The Haydn Variations serves as a useful sampler for Harnoncourt’s Brahms style as a whole, with an unforced vitality and many salient details subtly underlined – the cello line in the first variation, the unaggressive assertiveness of the eighth, the fluidity of the ninth (like a gentle boating song) and the way the finale’s repeating bass-line is kept within earshot (though without ever being allowed to dominate what is happening ‘on top’). Like Mackerras, Harnoncourt divides his violin desks and plays all the first-movement repeats. On an initial hearing, the First Symphony’s opening Un poco sostenuto seems a trifle soft-grained – that is, until you look at the score and note forte (not fortissimo) espressivo e legato. The pounding basses from bar 25 (disc 1, track 1, 1'49'') are beautifully caught by the recording, and the first-movement Allegro is both powerful and broadly paced. The Andante sostenuto slow movement, on the other hand, is both limpid and conversational, with trance-like dialogue between oboe and clarinet and sparing use of vibrato among the strings. Harnoncourt makes real chamber music of the third movement, though he drives the trio section to a fierce climax, and the finale’s first accelerating pizzicatos are truly stringendo poco a poco – the excitement certainly mounts, but only gradually. The first horn sports a spot of vibrato in the ‘big’ tune, there is much inner detail among the strings and the main body of the movement generates considerable tension. The closing moments are overwhelmingly exciting.

The Second Symphony’s first movement is relatively restrained and I was interested to note that the staccato woodwinds at bar 66 are softened to a more expressive legato. Harnoncourt’s strategy is to deliver a sombre exposition and a toughened development (there are some savage climaxes later on, especially the fortissimo at bar 402). This of course lends an extra justification to observing the ‘false security’ of the exposition repeat; in other words, the delayed development seems doubly powerful. Again, the slow movement is fluid and intimate, with some tender string playing at bar 45 (the violas’ contribution comes across quite beautifully). The third movement’s rustling trio is disarmingly delicate and the finale, tightly held, keenly inflected and heavily accented: the coda threatens to break free and the effect – as in the First Symphony – is thrilling. First impressions of Harnoncourt’s Third suggest a marginal drop in intensity. The headstrong string theme that drives home after the opening brass chords is hardly forte passionato and the blood-red cello-viola melody that sets in near the beginning of the development (bar 79) is rather less than forte agitato. And yet, the movement’s peroration is so powerful, so insistent, that one retrospectively suspects that everything prior to it was mere preparation. The middle movements work well (the Andante delivers a fine flush of string tone around bar 110), but it is the rough-hewn, flexibly-phrased finale that really ‘makes’ the performance.

Like the Third, the Fourth opens with less import than some of its older rivals. The second set sounds oddly cool and clipped (though note how clearly one hears horns backing cellos and basses from bar 55) and yet the development intensifies perceptibly, the recapitulation’s hushed piano dolce opening bars are held on the edge of a breath and the coda is recklessly headstrong. Harnoncourt makes a heartfelt statement of thepiano dolce cello melody at bar 41 in the slow movement (violin embellishments are also beautifully done), though its reprise some minutes later is moremezzo forte than forte espressivo. The top-gearScherzo is quite exhilarating – I cannot think of a more bracing stereo rival – and the finale, forged with the noble inevitability of a baroque passacaglia. Ultimately, Harnoncourt delivers a fine and tragic Fourth.

The two overtures are hardly less absorbing. TheTragic is a doggedly insistent Allegro non troppo, with finely-gauged tempo relations – though the opening is something less thanfortissimo. In the Academic Festival Overture, brass and timpani all but drown out upward leaps on the strings (i.e. at bar 84), though the tumbling horn triplets (at bar 181) add real fibre to the orchestral texture. ‘Stopped’ horns are especially effective later on and the closingGaudeamus igitur sounds appropriately resplendent.

This set gave me enormous pleasure and if, ultimately, I would return to various of its predecessors as a first port of call, Harnoncourt’s Brahms is the perfect antidote to routine, predictability and interpretative complacency. I urge you to hear it.'

The Haydn Variations serves as a useful sampler for Harnoncourt’s Brahms style as a whole, with an unforced vitality and many salient details subtly underlined – the cello line in the first variation, the unaggressive assertiveness of the eighth, the fluidity of the ninth (like a gentle boating song) and the way the finale’s repeating bass-line is kept within earshot (though without ever being allowed to dominate what is happening ‘on top’). Like Mackerras, Harnoncourt divides his violin desks and plays all the first-movement repeats. On an initial hearing, the First Symphony’s opening Un poco sostenuto seems a trifle soft-grained – that is, until you look at the score and note forte (not fortissimo) espressivo e legato. The pounding basses from bar 25 (disc 1, track 1, 1'49'') are beautifully caught by the recording, and the first-movement Allegro is both powerful and broadly paced. The Andante sostenuto slow movement, on the other hand, is both limpid and conversational, with trance-like dialogue between oboe and clarinet and sparing use of vibrato among the strings. Harnoncourt makes real chamber music of the third movement, though he drives the trio section to a fierce climax, and the finale’s first accelerating pizzicatos are truly stringendo poco a poco – the excitement certainly mounts, but only gradually. The first horn sports a spot of vibrato in the ‘big’ tune, there is much inner detail among the strings and the main body of the movement generates considerable tension. The closing moments are overwhelmingly exciting.

The Second Symphony’s first movement is relatively restrained and I was interested to note that the staccato woodwinds at bar 66 are softened to a more expressive legato. Harnoncourt’s strategy is to deliver a sombre exposition and a toughened development (there are some savage climaxes later on, especially the fortissimo at bar 402). This of course lends an extra justification to observing the ‘false security’ of the exposition repeat; in other words, the delayed development seems doubly powerful. Again, the slow movement is fluid and intimate, with some tender string playing at bar 45 (the violas’ contribution comes across quite beautifully). The third movement’s rustling trio is disarmingly delicate and the finale, tightly held, keenly inflected and heavily accented: the coda threatens to break free and the effect – as in the First Symphony – is thrilling. First impressions of Harnoncourt’s Third suggest a marginal drop in intensity. The headstrong string theme that drives home after the opening brass chords is hardly forte passionato and the blood-red cello-viola melody that sets in near the beginning of the development (bar 79) is rather less than forte agitato. And yet, the movement’s peroration is so powerful, so insistent, that one retrospectively suspects that everything prior to it was mere preparation. The middle movements work well (the Andante delivers a fine flush of string tone around bar 110), but it is the rough-hewn, flexibly-phrased finale that really ‘makes’ the performance.

Like the Third, the Fourth opens with less import than some of its older rivals. The second set sounds oddly cool and clipped (though note how clearly one hears horns backing cellos and basses from bar 55) and yet the development intensifies perceptibly, the recapitulation’s hushed piano dolce opening bars are held on the edge of a breath and the coda is recklessly headstrong. Harnoncourt makes a heartfelt statement of the

The two overtures are hardly less absorbing. The

This set gave me enormous pleasure and if, ultimately, I would return to various of its predecessors as a first port of call, Harnoncourt’s Brahms is the perfect antidote to routine, predictability and interpretative complacency. I urge you to hear it.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.