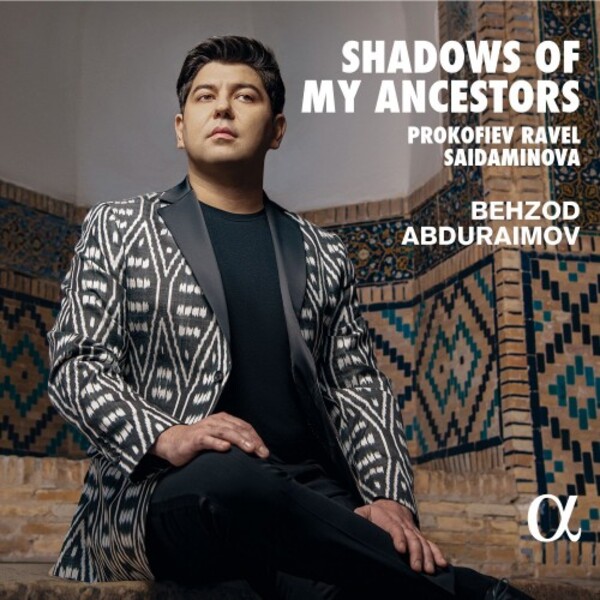

Behzod Abduraimov: Shadows of My Ancestors

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Alpha

Magazine Review Date: 02/2024

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 71

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: ALPHA1028

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| (10) Pieces from Romeo and Juliet |

Sergey Prokofiev, Composer

Behzod Abduraimov, Piano |

| The Walls of Ancient Bukhara |

Dilorom Saidaminova, Composer

Behzod Abduraimov, Piano |

| Gaspard de la nuit |

Maurice Ravel, Composer

Behzod Abduraimov, Piano |

Author: Jed Distler

Visual art and literature are at the core of the three piano cycles featured on Behzod Abduraimov’s latest solo release for Alpha. Originally commissioned by the Kirov in 1934, Sergey Prokofiev’s ballet based upon Shakespeare’s tragedy Romeo and Juliet had to wait until 1938 for its official premiere in Brno. By that time, however, the composer had already extracted two orchestral suites from the full ballet, along with 10 excerpts transcribed for piano solo. ‘Fantasias in the style of Rembrandt and Callot’ is the subtitle for Aloysius Bertrand’s collection of 66 prose-poems entitled Gaspard de la nuit, which planted the seeds for Maurice Ravel’s triptych of the same name. The Walls of Ancient Bukhara by Uzbek composer Dilorom Saidaminova (b1943) is a link in yet another three-way chain of inspiration. She regards this work as a homage to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, aiming to depict the ancient south-central Uzbek city’s historic centre in sound. Mussorgsky’s composition, in turn, took its cue from the artwork of Viktor Hartmann.

What’s more important, however, is the abundance of colour and poetry characterising Abduraimov’s stunning artistry. It takes only a handful of bars into Romeo and Juliet’s opening ‘Folk Dance’ to recognise that we are listening to a pianist who simply transcends his instrument. Throughout this release, one consistently gets caught up in Abduraimov’s gorgeous and focused sonority, his rock-solid rhythm, his boundless portfolio of shadings and nuances, plus a specificity of articulation that conveys a sense of air between the notes and the utmost in characterisation. The détaché chords and melodies of the second-movement ‘Scene’ evoke diverse woodwind timbres, while the Minuet’s bass lines are sung out rather than hammered. Because Abduraimov doesn’t race through ‘Young Juliet’, the scurrying scales truly dance on point. Have the arpeggiated chords of ‘Montagues and Capulets’ ever sounded so appropriately menacing as in this recording?

Abduraimov commences ‘Friar Laurence’ with a muted reserve that does not hint at the powerfully resonant climaxes just around the corner. The pianist’s deft alignment of the scurrying right-hand melodies and left-hand rhythmic displacements in ‘Mercutio’ evokes the asymmetric momentum in the Allegro precipitato finale of Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata. Notice, too, the lilting inner tension in the ‘Dance of the Girls with Lilies’, where Abduraimov infuses his seemingly steady tempo with tiny rubato droplets. All I can say is that if the minuscule dynamic gradations in the 10th piece’s final pages don’t take your breath away, you haven’t been listening.

Whatever Dilorom Saidaminova owes to her professed Mussorgsky role model, her evocative music entirely inhabits its own world. The sparse and incantatory lines of the opening ‘Mosque Kalon’ seem to emit from different pianos in different acoustics via Abduraimov’s hand balances. Imagine ‘The Chase’ from Bartók’s Out of Doors suite transcribed for a Middle Eastern Qanun and you’ll have an idea of the second movement, ‘Samanid Kingdom’, where Abduraimov’s suave rapid scales and mellifluous repeated notes also emerge in three-dimensional perspective. ‘Tomb of Ismail Samani’ largely consists of soft, slow-moving melodic lines embellished by occasional flourishes. All of this material brackets a brief , harrowing central climax.

The open fifths that launch ‘Domes’ quickly evolve into a variety of arpeggiated figurations; check out Abduraimov’s magical handling of the gorgeously disembodied keyboard-writing between 1'26" and 1'51". Then there’s the menacing asymmetry of ‘Minaret of Death’ to digest, as well as the sixth and seventh movements’ fragile left-hand lament in tandem with gentle high-register clusters. Saidaminova has a most caring and sensitive interpreter in Abduraimov, and I hope that his recording will inspire pianists to investigate this cycle; it’s a major find.

Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit, of course, needs no special pleading. Nor does it need yet another recording, considering the amount of standard-setting and bar-raising performances that have stuffed the catalogue beyond capacity. Since pianophiles know the great recorded Gaspards like the back of their hands, what can one possibly add to the legacy of Walter Gieseking’s 78s, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s 1959 BBC traversal, Robert Casadesus, Martha Argerich, Ivo Pogorelich, Beatrice Rana, Abbey Simon, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Herbert Schuch, Steven Osborne and so on, ad infinitum? However, I’ve always maintained that artistic excellence is its own justification, and Abduraimov’s Gaspard easily takes a place at the table among the reference versions.

From the start, ‘Ondine’ stands out for the sheer evenness and glowing transparency with which Abduraimov shapes the persistent alternating right-hand chord/single-note patterns. He’s also more attentive to bass lines than most pianists, while the cannily timed glissandos further enhance the performance’s seductive subtext. In an era when young pianists often mistake ‘Le gibet’ for late Beethoven and stretch out the music to death, Abduraimov’s straightforward fluidity is just the antidote. The billowy chords, obsessively tolling B flats and accented motifs occupy their own textural planes, coexisting yet never colliding or turning into mush.

Following such focused, controlled and intensely calibrated music-making, Abduraimov pounces upon ‘Scarbo’, casting all inhibitions to the wind and allowing his virtuosic impulses to go for broke in the climaxes. He matches and sometimes surpasses Pogorelich’s daring pedalling gambits, while his clear and variegated voicing of low-register chords enables one to hear pitches instead of mud. Likewise, you infer long and shapely lines within the streams of repeated notes instead of percussive pellets. What is more, Abduraimov proves consistently cognisant of the music’s darkly mercurial narrative, especially in regard to his scaling of dynamics for maximum dynamic and emotional effect. Abduraimov’s compelling musicianship and awe-inspiring pianism also benefit from the concert-hall realism and top-to-bottom impact of Alpha’s superb recorded sound. Naturally, it’s too early to declare ‘Shadows of my Ancestors’ Gramophone’s best piano release of 2024. Yet it unquestionably deserves to be a contender, and reaps new rewards with each rehearing.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.