BEETHOVEN Symphony No 3 (transcr Liszt) MOZART Piano Concerto No 20 (transcr Alkan) Paul Wee

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: BIS

Magazine Review Date: 12/2022

Media Format: Super Audio CD

Media Runtime: 83

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: BIS2615

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 3, 'Eroica' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Paul Wee, Piano |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 20 |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Composer

Paul Wee, Piano |

Author: Harriet Smith

In September 2015 Jeremy Nicholas lamented that José Raúl López’s performance of Mozart’s D minor Concerto as reflected through the prism of Alkan did neither composer any favours. He ended: ‘This will have to do until a Hamelin tackles it.’ Well now a Hamelin has done just that, and his name is Paul Wee: lawyer by day and pianist by night.

What’s immediately striking is how fast Alkan draws you into a world where you don’t miss the orchestral colours of Mozart’s original. That’s as much down to Wee, his Steinway and the splendid engineering (courtesy of David Hinitt at Wyastone Concert Hall) as the transcription itself. The score itself isn’t overburdened with instructions – dynamics and pedalling, yes, but not much in the way of phrasing or articulation, for instance. The imagination with which Wee brings the concerto to life is staggering and the way he differentiates between tuttis and solo writing adds much to the drama; impressive, too, is the way he dives into the development section, seething turbulence contrasting vividly with the gentler music, and even where textures become really involved (track 5, from 7'56", for instance) there’s a Hamelin-esque clarity to his thinking that ensures the vital lines always come through. The cadenza is, of course, Alkan’s own, and it’s gloriously OTT in its virtuosity, harmonic adventuring and scale, all of which Wee handles with delightful insouciance, before matters are brought back in hand with a peremptory trill signalling the return of (purer) Mozart.

The serenity of the Romanze is unerringly captured, with colouring and weighting that emulate the original textures – piano alone and then enveloped in strings. Touches of minor (track 6, from 2'36") are given with just the subtlest of slowings, while the more full-blown minor-key passage (from 4'00") is given its head without ever sounding aggressive, and the placing of the final chords is spot on. From here we launch into a finale that Alkan labels Prestissimo, rather than Mozart’s Allegro assai. There are so many challenges in this movement, especially at this tempo: obsessive repeated notes that can easily become percussive, or weighty textures merely murky, but not here. And Wee conjures, in the quieter moments such as the soloist’s new entry (track 7, 0'56") or the delicate writing in the upper reaches (3'34"), extraordinary nuance and delicacy. Again, Alkan’s cadenza could seem merely vulgar but Wee absolutely believes in it and delights in its outlandish flights of fancy. As we return to the 18th century, there’s a real sense of triumph as the minor finally transforms into the major.

Beethoven’s symphonies as rethought by Liszt are, unlike the Mozart-Alkan, almost commonplace these days. What the Third, in particular, gains by being heard in this form is the single-mindedness of its invention, the ferocious tautness of his symphonic vision. So is Wee up to it? Oh yes, absolutely. And, like the Mozart, his tempos are part of that success: he brings a real élan to the opening movement, conveying Beethoven’s obsessiveness without ever becoming aggressive. The sheer audacity of the composer’s shifting tonalities, too, is illuminated here to rare effect.

In the funeral march he’s a degree more grief-stricken than Gabriele Baldocci, whose recording impressed Jed Distler, but his tempo never drags, so clear is the sense of line and underlying tread, while the break into fugal writing (track 2, 7'29") has a barely concealed fury about it – a quality that derives as much from Wee’s absolute focus as from the notes on the page.

But it’s perhaps the Scherzo, which I’ve had on replay countless times now, where this reading really puts others in the shade: for Wee can actually take it at a tempo that emulates orchestral accounts – Katsaris, Baldocci, Howard and Biret are all slower (some much slower), but Wee has technique to spare. The repeated notes propel the music forwards in an endless dance; they go with a real sense of swing and, as the writing gets more involved, nothing fazes this pianist.

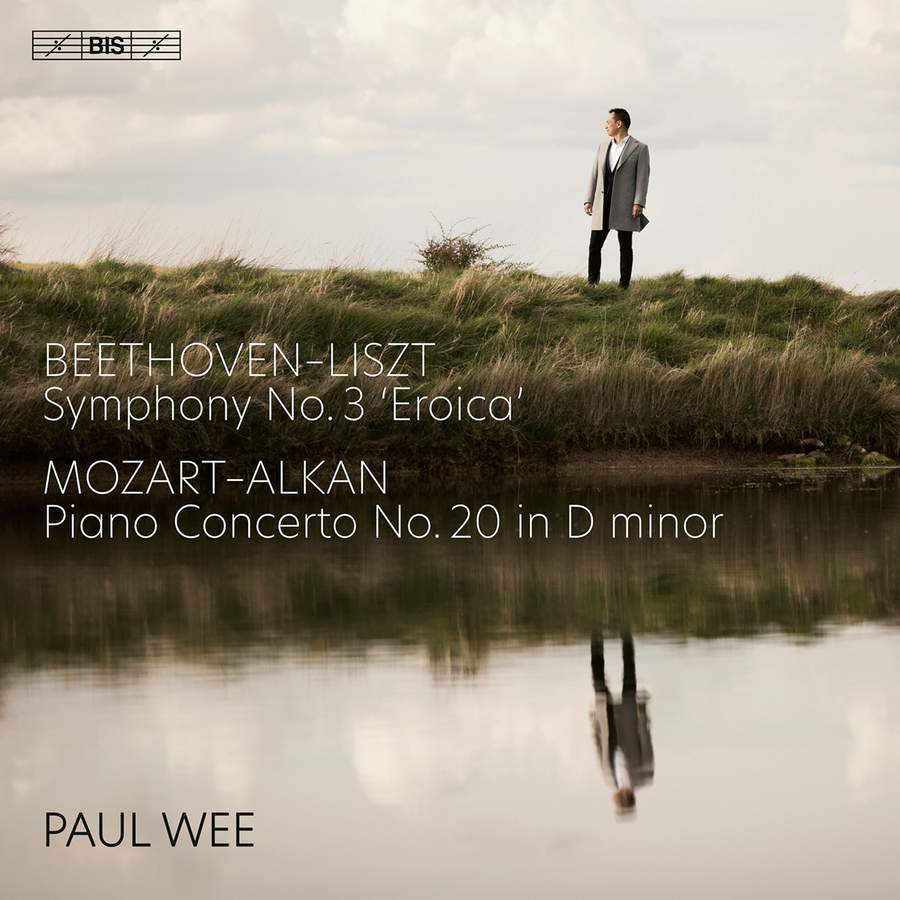

Those qualities of drive and focus, which are so fundamental to Beethoven’s symphony and which also underpin Wee’s interpretation, continue into the finale. Here, his ability to sustain the momentum is remarkable, not just in the spirit of the dance but also in the points of reflection: as the theme solidifies into a chorale (track 4, 6'20") it has true poignancy and you almost forget that this was originally a symphony – for a couple of minutes it seems to have morphed into a piano fantasy. Not for long, though: as the tempo picks up for the final Presto, Wee astounds once more with his fearless daredevilry. The cover photo, channelling Caspar David Friedrich’s solitary hero, is entirely apt.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.