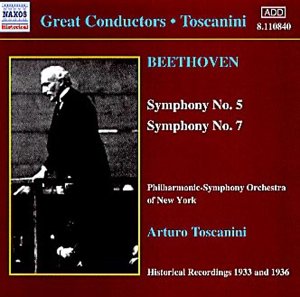

Beethoven Symphonies Nos. 5 and 7

The hoary old Maestro rockets across the years with as much force as ever‚ upstaging his wellgroomed but unchallenging new rival

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Naxos Historical

Magazine Review Date: 2/2002

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 77

Mastering:

ADD

Catalogue Number: 8 110840

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 5 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Arturo Toscanini, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra |

| Symphony No. 7 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Arturo Toscanini, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra |

Author:

I don’t know who to pity more: the budding maestro who hears this Beethoven Fifth before attempting to conduct the work himself‚ or the one who doesn’t. Either way‚ Toscanini is a nearimpossible act to follow. But then in a sense he was fortunate. He didn’t have a fat record catalogue full of Rostrum Greats to live up to and he wasn’t under pressure to say something new‚ or at least something different. On the contrary‚ Toscanini’s avowed mission was to clean up where others had indulged in interpretative excess. And he could as well have been cleaning up for the future. In November I was humming and hawing over Sir Simon Rattle’s fascinating but fussy Fifth with the VPO (EMI). Had this new Naxos release been to hand‚ I might have focused Rattle’s calculated individuality in relation to Toscanini’s directness and elasticity.

There are numerous Toscanini Fifths in public or private circulation‚ at least four of them dating from the 1930s. This one is lithe‚ dynamic and consistently commanding. It was in fact RCA Victor’s second Toscanini Fifth‚ tauter and tidier than its betterrecorded live 1931 predecessor (due out soon on Naxos and currently available on Pearl)‚ though like the earlier version it was never actually passed for commercial release. Comparing it with Toscanini’s wellknown 1952 NBC recording finds numberless instances where a natural easing of pace helps underline essential transitions‚ such as the quiet alternation of winds and strings that holds the tension at the centre of the first movement. The glow of the string playing towards the close of the second movement has no parallel with the 1952 version and while the NBC Scherzo is better drilled‚ this finale really blazes. Mark ObertThorn has done a firstrate job with the sound‚ focusing the orchestra’s whispered pianissimos (so much quieter than on Toscanini’s NBC records) while keeping surface noise to a workable minimum.

The commercially released 1936 New York Seventh has already been hailed as a classic. On this excellent transfer there’s added musical interest in that ObertThorn offers us two versions of the first movement‚ one with a broad ‘first take’ of the opening Poco sostenuto‚ another with a retake of the same passage that pushes the tempo significantly forwards. My view is that while the first version is more imposing the second facilitates a more natural segue to the main body of the movement. Either way‚ the Vivace has a valiant‚ dancing quality‚ less aggressive than its joyous but fierce NBC successor and with ample flexibility between episodes. The poised Allegretto is warmed by expressive portamentos‚ and the Scherzo must be one of the first on disc to match Beethoven’s fast metronome marking. As with the Fifth‚ Toscanini’s ability to gauge pauses to the nth degree – in this case the rests that separate the finale’s opening fortissimo rallying calls – is truly inimitable.

And so to Thomas Dausgaard and the latest leg in Simax’s wellrecorded ‘Complete Orchestral Works of Ludwig van Beethoven’. Although not played on period instruments‚ the approach is very PC. All repeats are observed and the forces employed are relatively modest. Violin desks are spatially separated; tempos more or less fit Beethoven’s printed requirements and the style of string playing favours light bowing and a minimum of vibrato. You know the sort of thing‚ I’m sure. The first movement has ample dynamic shading and the Allegretto’s opening theme is subtly accented every two bars. Dausgaard takes a bracing view of the scherzo and finale‚ not dissimilar to Toscanini’s in principle‚ but aeons removed from it in overall effect. Fresh it may be‚ but the nobility and the visceral thrill of Toscanini’s prewar version remains unchallenged.

I leave readers to take it on trust that far from donning my anorak or indulging in obsessional nostalgia‚ I do actually believe that Toscanini’s Seventh delivers a truer‚ more compelling and infinitely more powerful musical message than Dausgaard’s. The Egmont incidental music is similarly alert‚ crisper in execution than James Conlon’s recording‚ though no less imaginative. Here‚ as there‚ the Overture will not please those who prefer a tougher line in its principal arguments: Dausgaard’s breathless performance borders on the skittish. As to couplings for Egmont (if that happens to be your main priority)‚ and given the choice between Conlon and the excellent Wanderer Trio in the Triple Concerto and Dausgaard in the Seventh Symphony‚ I’d plump for the Conlon and the Concerto.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.