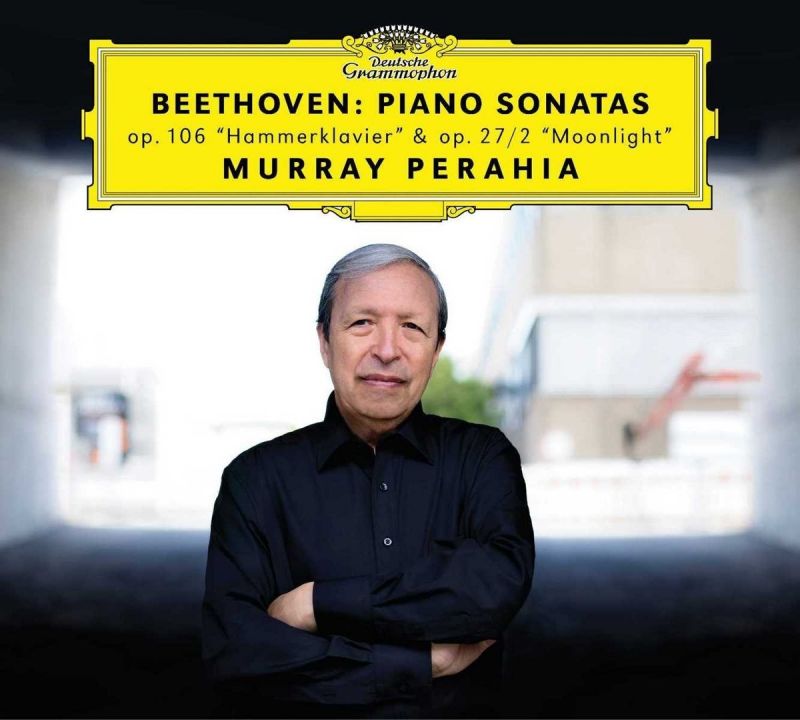

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonatas Nos 14 & 29 (Perahia)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Genre:

Instrumental

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Magazine Review Date: 03/2018

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 56

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 479 8353

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Sonata for Piano No. 14, 'Moonlight' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Murray Perahia, Piano |

| Sonata for Piano No. 29, 'Hammerklavier' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Murray Perahia, Piano |

Author: Richard Osborne

A further assumption it might be useful to set aside, as we attend to what Murray Perahia calls ‘two of the most radically groundbreaking of the composer’s 32 piano sonatas’, is that the Hammerklavier is the more difficult of the two pieces. I’m not thinking here of the finger-wrenching challenge of actually delivering the Hammerklavier, something the unbridled fury of the finale of the earlier sonata interestingly presages. Rather, I’m thinking of the imaginative and technical challenges that the emotionally complex Sonata quasi una fantasia in the then alien key of C sharp minor presents to the player: first in seeking out its essence, then in distilling that essence on whatever keyboard circumstance or time provides. (As Charles Rosen observed, the sonata’s finale shredded the pianos of 1801 as surely as its opening movement troubles more modern ones.)

One of the many problems presented by the meditative opening movement is that there is no ready-made solution to the question of the speed at which the music should move, other than that which the accomplished interpreter discovers for himself, be it Ignaz Friedman in one of the earliest of all recordings (Columbia, 2/27) or Murray Perahia today. Thus Solomon, in a famous HMV recording (10/54), takes nearly nine minutes over the movement, whereas Perahia, in his luminously voiced yet at the same time emotionally riven performance, takes a little over five.

And make no mistake, this is desolate music. ‘A pale light glimmers above the whispered pianissimo triplets, from whose dark depths the grief-laden melody ascends’, wrote Wilhelm Kempff, whose 1956 mono recording (DG, 10/57) is not dissimilar to Perahia’s, for all that Kempff occasionally allows, for expressive effect, a barely perceptible pause in those whispered triplets. We re-encounter this mastery of musical discourse, albeit at greater length and on a higher plane, in Perahia’s free-flowing yet lofty account of the great soliloquy that stands at the heart of the Hammerklavier.

Kempff was one of the few pianists of his generation who avoided ponderousness in the Moonlight’s middle movement. Perahia, too, catches well the dance’s melancholy grace and epigrammatic charm; and though his account of the Trio is properly robust, the almost hallucinatory quality Beethoven brings to the drone bass in the Trio’s concluding bars is not lost on Perahia. Thus, when the dance returns, it too appears to have taken on something of the mood of barely suppressed pain that is the sonata’s abiding characteristic.

It’s been said that the work’s undeniably angry finale tries too hard, is too repetitive. There’s no sense of that in Perahia’s reading, which has exactly the right degree of implacability, for all that he’s happy to play Beethoven’s game of false dawns with a gracious approach to the recapitulation and a decorous descent from the coda’s emblazoning high trill to the pit below. The ferocity with which the two last chords are delivered suggests, however, that the composer’s travails are not yet over.

A late chapter in this same story arrived with the composition of the Hammerklavier in 1818, by which time Beethoven had become, in JWN Sullivan’s words, ‘the great solitary’, ‘a man of infinite courage, infinite suffering’.

Much ink has been spilled on how rapidly the first movement should travel. ‘Uncommonly quick and fiery’ was Czerny’s judgement, an approach that echoes the spirit, if not the letter, of Beethoven’s hair-raising metronome mark. Artur Schnabel attempted that in his legendary HMV recording (11/36) made in exile in London in 1935, by which time the once ‘flawless’ playing (Claudio Arrau’s testimony) was no longer entirely flawless. For all his own tribulations in recent years, Perahia’s playing pretty well is. His approach to the first movement is never reckless yet it’s essentially ‘quick and fiery’, the fearless ambassador to a still untamed spirit.

Perahia is artist enough to know that great art is never, of itself, ugly. It may be Beethoven’s instinct to push every component of the dauntingly complex contrapuntal finale to its logical conclusion (and beyond) but Perahia, though honouring the intent, declines to turn the music into a rout. In matters of musical diction, lucidity matters.

Not long before the sonata’s end, Beethoven introduces a three-part fugato, a lyric inspiration of rare beauty, limpid in D. In the context of this carefully gauged programme, we might be tempted to recall the similarly precarious beauties of the C sharp minor Sonata’s opening movement – except that, for some inexplicable reason, the producers have placed the sonata after the Hammerklavier. That lapse notwithstanding, this is a disc, naturally and vividly recorded, of rare distinction and pedigree.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.