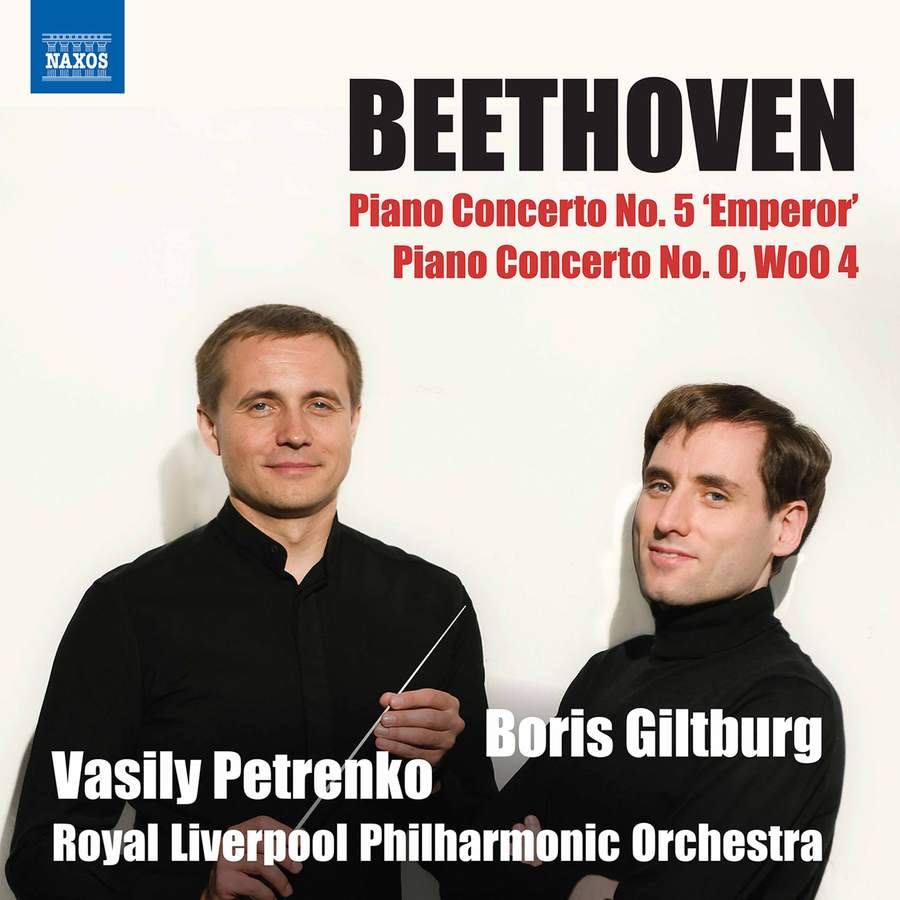

BEETHOVEN Piano Concertos Nos 5 & 0 (Boris Giltburg)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Naxos

Magazine Review Date: 05/2022

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 63

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 8 574153

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, 'Emperor' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Boris Giltburg, Piano Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Vasily Petrenko, Conductor |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Boris Giltburg, Piano Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Vasily Petrenko, Conductor |

Author: Patrick Rucker

I first heard Boris Giltburg shortly after his victory in 2013 at the Queen Elisabeth Competition, when Marin Alsop, who had conducted the orchestral finals in Brussels, invited the young Russian-born Israeli to play Rachmaninov’s Fourth Concerto with her orchestra in Baltimore. It was an auspicious debut, and I recall thinking how rare it was for a young pianist to exhibit in such perfect proportion the qualities of a first-class Rachmaninov player.

Fast forward nine years. Giltburg is now 37 and has released, if I’ve counted correctly, as many as 14 recordings. He’s more than fulfilled his early promise as a fine Rachmaninov interpreter. There’s also been a Dvořák Piano Quintet (Supraphon, 11/17), a programme of Schumann cycles (Naxos, 3/15) and a set of Liszt’s Transcendental Études (Orchid, 10/13), but mostly it’s been Beethoven and the Russians. The present release is of the Fifth Concerto, coupled with the juvenile E flat Concerto, performed in a solo piano version made by Beethoven around 1798, which need not detain us.

In Op 73, from the outset, it may seem that Vasily Petrenko and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic are a tad front and centre, punching a bit in excess of their weight. However, as the movement unfolds, it becomes evident that perhaps they are offering encouragement to one of the more foursquare, docile, even diffident readings of the solo part I’ve encountered. All those things that give the Emperor its special quality and status – its majesty, grandeur, the sometimes mystical subtlety of power and splendour – seem to have fled into the night. By the arrival at the exquisite Adagio, it’s clear that this literalist approach is not only here to stay, but intentional. Surely it requires a tremendous amount of artistic self-effacement to take the lofty poetry of the slow movement and the unalloyed kinaesthetic joy of the Rondo and reduce them both to something quite this routine and pedestrian.

What is going on here? Battle fatigue? An attempt to clear away the accumulated underbrush of personalised interpretation? An attempt at establishing a new school of Beethoven interpretation, with the central tenet ‘less is more’? Some may like it. Personally speaking, if your aim is to portray canonic art to others, it seems to me that a point of view might be a good place to begin.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.