BEETHOVEN Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 3

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: NIFC

Magazine Review Date: 07/2015

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 86

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: NIFCDVD005

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

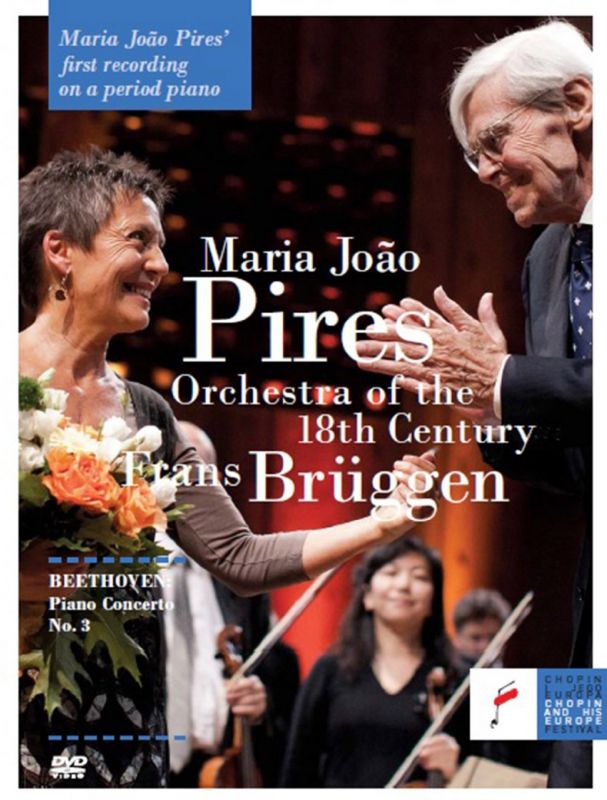

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Frans Brüggen, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Maria João Pires, Fortepiano Orchestra of the 18th Century |

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: NIFC

Magazine Review Date: 07/2015

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 92

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: NIFCDVD004

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

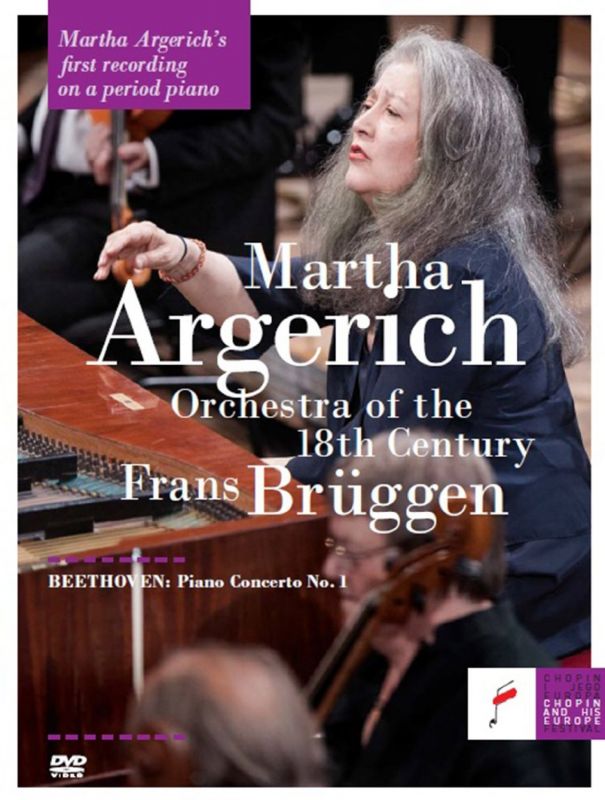

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Frans Brüggen, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer Martha Argerich, Piano Orchestra of the 18th Century |

Author: Richard Osborne

This is not, then, an instrument of Beethoven’s period. (For that you must go to Robert Levin’s fine Archiv set of the concertos.) Beethoven did own an Erard, presented by the company to ‘Mr Bethoffen à Vienne’ in 1803, but that was a very different creature to this 1849 model with its metal frame, double escapement action and 7 octave keyboard.

Both DVDs carry a 40-minute documentary about the orchestra. Worthy as this is, I would have preferred a film about the Erard. With its powerful bass and the bell-like brilliance of its top registers (a tricky combination, unerringly matched by Pires in the wider tessituras of the C minor Concerto), not to mention a system of under-damping which requires fresh thinking about pedalling, it must be a challenge to play. Still, the end results as we have them here are a joy.

Neither pianist plays less brilliantly or less expressively than on a modern grand. It’s simply the effects that can be intriguingly different. The brilliance of the Erard’s top registers, which so commended the instrument to pianists such as Saint-Saëns and Planté, serves both concertos particularly well. After all, it’s in the dash, dazzle and stellar imaginings of these high-lying passages that so much of the inner content of Beethoven’s keyboard concertos lies.

The C major Concerto has long been one of Martha Argerich’s party pieces. Despite Brüggen’s very ‘un-period’ – ‘laboured’ would be a less polite term – pacing of the first-movement ritornello, Argerich is able instantly to energise proceedings, driving the music forwards while at the same time using the Erard’s particular sound palette to bring out the martellato character of Beethoven’s more bullish writing. Similarly in the finale she brings a dashing, jazzy, appropriately improvised feel to the music. In a concerto that needs to be driven, she drives the Erard strongly on. In the more emotionally complex C minor Concerto, Pires prefers a more measured approach, quietly husbanding the instrument’s resources with her own sure and discriminating touch.

Pires recently recorded the Third and Fourth concertos with Daniel Harding and the Swedish RSO (Onyx, 10/14), performances which drew an appropriately eloquent response from Bryce Morrison. Here is a pianist, he wrote, who ‘appears to do so little and ends by doing everything’. In an age of ‘interpretation’, Pires’s performances ‘are simply of another order’. And so it is here. It’s a wonderful performance, during which Brüggen and his players come fully into their own. I also find Brüggen a kinder accompanist than Harding, probably because the contemporary fad for making modern orchestras play in a ‘period’ style can often etiolate the sound or even brutalise it.

Sviatoslav Richter has a diary entry: ‘I’m fiercely opposed to televised broadcasts. The image prevents you from listening and there’s nothing interesting to see.’ He might have thought differently here. Watching the touch on this fine old instrument of these two great mistresses of their art, and relishing the sounds they conjure forth, is an education in itself. Both are exceptional releases.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.