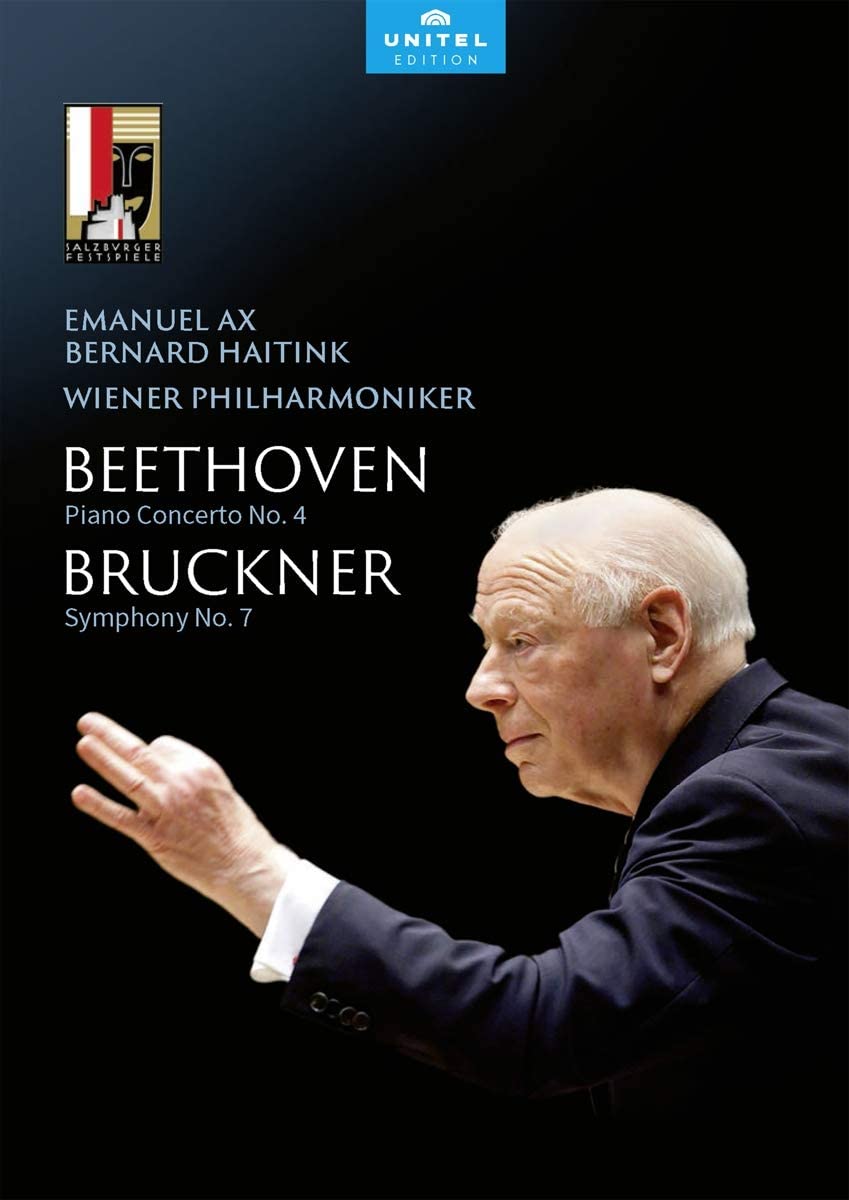

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No 4 BRUCKNER Symphony No 7 (Haitink)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Unitel Editions

Magazine Review Date: 10/2020

Media Format: Digital Versatile Disc

Media Runtime: 116

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 802208

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emanuel Ax, Piano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra |

| Symphony No. 7 |

Anton Bruckner, Composer

Bernard Haitink, Conductor Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra |

Author: Peter Quantrill

Towards the end of what became his adieu to the podium, Bernard Haitink led the Seventh Symphony of Bruckner with three orchestras. In itself this concentration was hardly remarkable: having seen it under his baton with seven different ensembles in London during the past 30 years, I think of the Seventh as Haitink’s signature work, the yang to the yin of Mahler’s Sixth. He has always conducted the musicians as much as the score, and the precise tints of his final accounts with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic and the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics were accordingly individual. Something about the density of the Berlin sound (preserved both on LP and the Digital Concert Hall) elicited a performance of tremendous grandeur, impressive on its own terms, yet yielding in the final analysis to the more pliant caress of his VPO concerts, the first of them presented complete here.

There is no place in the Seventh for the flinty-eyed vision of the abyss that stamped Haitink’s approach to the unfinished Ninth with an increasingly memento mori bleakness. Wholeness in the here and now is instead established from the outset with the patient but subtly inflected first theme’s unfolding by the Viennese cellos. Compared to his Concertgebouw recordings, the difference is one of being and becoming. Richard Osborne remarked on the ‘deliberately unmoulded’ nature of the second recording (Philips, 4/79); no one could reasonably say the same of his final address to the piece, listening to the Gesangvoll intensity of the second theme once recapitulated, the additional flesh on the bones of the usually perky third theme and its marked preparation for the magical first entry of the timpani, sehr feierlich (very solemn) indeed.

Haitink’s basic tempo for the first movement, more Allegro than moderato, used to ruffle feathers. Half a century on, coming after diverse Sevenths from Abbado, Harnoncourt and Iván Fischer, it seems ahead of its time, as well as flowing from the uncomplicated cantabile line cultivated by the conductor’s first mentor, Eduard van Beinum. Meanwhile Haitink himself has travelled upstream; but rather than invoking a sacred-Wagnerian source for this music in the manner of Barenboim or Thielemann, his broader tempos, allied to some striking rhetorical cadences and the Vienna Philharmonic’s playing at its most luminous and transparent, establish a Beethovenian model of symphonic innovation taking inspiration from nature and folk culture, one scarcely to be foreseen from the accomplished but placid account of the Fourth Piano Concerto.

This is most strikingly true of the Scherzo. By the clock almost as slow as Celibidache in Munich, the broad impetus and airborne phrasing here revisit the world of the Fourth Symphony (another plank of Haitink’s farewell season), only now imbued by the composer with years of accumulated experience in post-Schubertian orchestration to which decades of brass-led performances, even ones as refined as the conductor’s latter-day Chicago reading, have not done full justice.

Just as he takes a new, legato approach to the great C minor trench through the middle of the first movement, bringing round the recapitulation with Mozartian naturalness and economy, so Haitink now places the two themes of the Adagio not in contrast but complement (far more convincingly so than in his Bavarian Radio Beethoven Ninth – BR-Klassik, 2/20). Leaving aside a tiny moment of confusion when they intertwine, he imparts a rare sense of complete but provisional satisfaction to the movement’s cymbal-capped climax, having a farther horizon in sight.

So does the funeral march of Abbado’s valedictory Eroica in Lucerne (Accentus, 9/14); but the performances are surprising in equal and opposite ways, Abbado never having previously got to the heart of Beethoven’s symphony, whereas, we might have anticipated, Haitink would beat a familiar path to the summit of the Seventh. Wrong again. There is no precedent in his discography – none else on record I know of – for the ascent to and mighty caesura at fig S in the score, yet the moment emerges as the inevitable outcome of the main theme’s titanic struggle for stability. Thereafter, instead of nervous intensity, there is only (only!) a steady pulse and clear-sighted purpose that requires no pseudo-mystical slowing down for its consummation but takes the coda as if in a single breath. Like Karajan’s farewell Seventh (DG, 5/90) – with the same orchestra, more fallible, more ardent, no less absorbing – it’s the work of a lifetime.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.