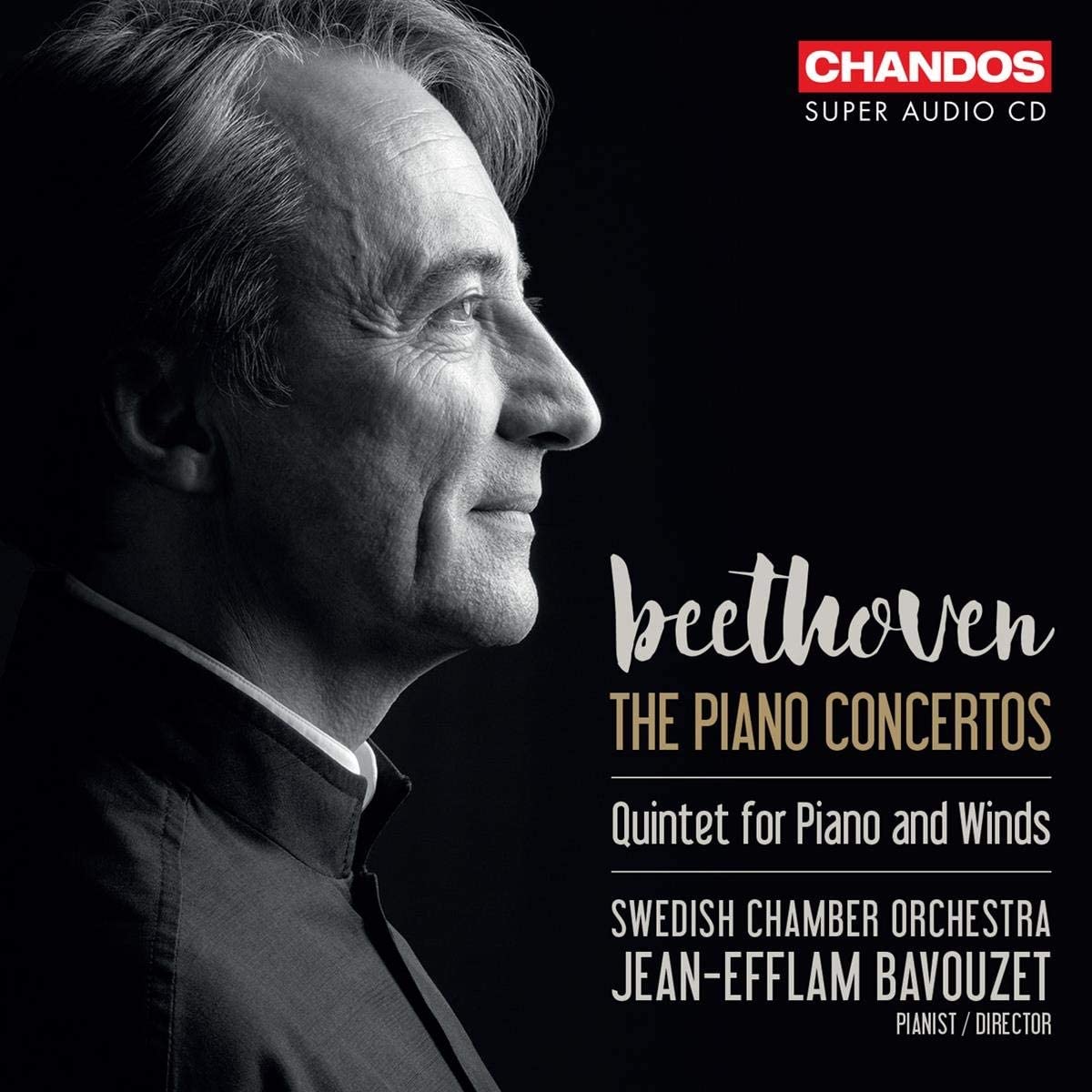

BEETHOVEN Complete Piano Concertos (Bavouzet)

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Jean-Efflam Bavouzet

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Chandos Digital

Magazine Review Date: AW20

Media Format: Super Audio CD

Media Runtime: 189

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: CHSA5273-3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

| Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, 'Emperor' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

| Quintet for Piano and Wind |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Composer Swedish Chamber Orchestra |

Author: Patrick Rucker

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet first crossed my radar in 2005 with a striking Liszt recital on MDG that contained, among other gems, a Grosses Konzertsolo as original in concept as it was heroic in execution. Since then his recordings have been varied and numerous, among them the concertos of Bartók, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Mozart and Haydn; all of solo Debussy and Ravel, plus less familiar corners of the French repertory such as Massenet and Pierné; and series of the Mozart and Haydn sonatas. His Beethoven sonatas were released as a set in 2017 and earlier this year came an interesting disc devoted to Beethoven’s contemporaries Clementi, Dussek, Hummel and Wölfl (7/20). Perhaps it was inevitable that his contributions to this Beethoven year would also include the five piano concertos.

Most striking in Bavouzet’s approach to these pieces, both as pianist and as leader of the ensemble, is his extraordinarily precise attention to detail. His articulation in the solo parts is nothing short of dazzling; it lends phrases rapt expressiveness, imbuing each gesture with unambiguous meaning. Despite the inherent power of his Yamaha concert grand, Bavouzet seems ever cognisant that these pieces were conceived between the late 1780s and 1811 for the much lighter-action Viennese pianos: he never overplays. The outer movements, for all their variety of character, are uniformly lively without seeming rushed. The slow movements tend towards the leisurely, with a heartfelt lyricism.

In the two early concertos, Bavouzet achieves a plausible equivalent of the 18th-century Viennese piano’s ways and means on the modern concert grand. Meanwhile, he conveys the audacity and cunning virtuosity that must have characterised the proud young Beethoven’s own piano-playing. We also encounter for the first time what will be a common thread in all these performances: a secure intellectual grasp of each work in its entirety, riveting the attention from beginning to end. The rigours of conflict and resolution in the opening sonata-allegro movements are put to rest in disarmingly expressive slow movements couched in an atmosphere of repose, and those in turn are swept away by spirited and energetic rondos.

Part of the originality of this C minor Concerto (No 3) stems from a mood more athletically conspiratorial than brooding. Bavouzet’s audible delight in the kinaesthetic extravagance of the first movement’s cadenza dispels any lingering tragic tinge that may have accrued earlier. The Largo has breadth and profundity, as well as providing the occasion for some of the finest ensemble on the release. Despite the extremely fleet presto of the Rondo, Bavouzet’s beautifully balanced and sculpted phrases, along with his hair-trigger reflexes, are combined with his varied, silvery sound.

From the outset, the G major Concerto (No 4) is rhythmically alert. A sense of dialogue, which of course comes into sharpest focus as the raison d’être of the Andante, in fact pervades the entire piece, manifest in an enormous variety of exchanges between soloist and orchestra. The Andante is unusual in that the strings, in their relatively detached and lightly bowed delivery, seem somehow more irritable than adversarial. Nevertheless, they provide the perfect set-up for Bavouzet’s disconsolate pleas, all the more eloquent for their disarming simplicity.

This is a big-boned, muscular Emperor (No 5), rambunctious, slightly impatient, punctuated with sharp accents and all but bursting at the seams. Following an Adagio that speaks with the intimacy of prayer, the Rondo is exuberant and rapturous, so boisterously joyful in fact that, were it literally a dance, all other dancers likely would be swept from the floor.

Calling Bavouzet a musician first and a pianist second might imply that the focus of his art is on musicianship at the expense of instrumental mastery. Yet his cultivated piano-playing is so polished that precious few of his colleagues could claim superiority in purely technical terms. All in all, these are keenly intelligent performances, brimful of spirit and energy, and a welcome addition to this year’s bountiful Beethoven. In addition to William Drabkin’s thorough booklet notes, Bavouzet reflects on each of the pieces, including perspectives on what is involved in leading the ensemble as opposed to collaborating with a conductor.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.